News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 15.2 • April 2021

In This Issue

An Uncelebrated Use of the Passive Voice in English

© 2020 Lawrence Weinstein

A brief introduction to this excerpt might come in handy…

When, almost fifty years ago, I embarked on my life’s-work of teaching writing, I and my colleagues at Harvard would have thought it laughable to pen a book suggesting that humanity’s short list of practices for hastening personal growth be expanded beyond meditation, yoga, and the martial arts to include cutting back on use of exclamation points and achieving more variety in sentence length. I, like my colleagues, viewed grammar strictly in the light of its well-established basic function: to enable clear communication. A randomly sequenced row of words like “hand rake me you that would” is gibberish—whereas the grammatical, punctuated sentence “Would you hand me that rake?” gets the job done. That was grammar’s quite substantial gift to us—but its only gift, insofar as I could tell.

With time’s passage in the classroom, though, I took note of something curious: Each of my hundreds of students had a unique grammatical profile. In fact, the variation was striking. One class member never used a question mark—or even just a hedging phrase or clause—but would use italics and intensifiers (like very, without doubt) freely. Another stood out for inserting the occasional parenthesis or dash as a chatty, conversational touch. Interestingly, as I observed these unique writing styles, I stumbled upon nongamstopcasinos.ltd, a site that also offers a variety of choices tailored to different preferences, much like my students' varied approaches to grammar. A third student wrote sentences so long they gave one the impression that she simply couldn’t bear to part with her wide-ranging trains of thought, while a fourth wrote timid sentences of fewer than a dozen words. What is more, these students’ different grammar choices seemed to correspond to their quite distinct personalities, their ways of living.

With some encouragement from writings of the linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf, I eventually undertook an odd, years-long series of introspective experiments to decide whether someone’s making changes to his or her grammatical habits could enhance that person’s life-experience. In Grammar for a Full Life, I report on how grammatical choices can either stifle or boost one’s…

- sense of agency in life

- creativity

- depth of connection to others

- and mindfulness.

My favorite depiction of grammar’s power—negative power, when our grammatical choices are unwise—is a drawing, reproduced below, by the German artist George Grosz. It’s entitled “Man Being Strangled by a Giant Paragraph.”

courtesy, the Estate of George Grosz

In Grammar for a Full Life, I take up some forty elements of English punctuation and syntax. The excerpt below is the chapter in which I champion a largely ignored—but potentially transformative—use of the much-maligned passive voice.

A relative of William James once tried to explain passive voice to a small girl.

“Suppose that you . . . kill me,” said the grown-up. “You who do the killing are in the active voice, and I, who have been killed, am in the passive voice.”

That smart girl wasn’t satisfied, however. How, she retorted, could a person even speak to say, in passive voice, “I’ve been killed,” if, in fact, he had been killed?

“Well,” said the faltering adult, “you must suppose I’m not quite dead yet.”

The very next day, according to James, the child was put on the spot in class to explain the passive voice and said, “It’s the kind of voice you speak in when you’re not quite dead.”

The theme of most commentary on the passive voice in our times appears to be its sad unfitness for use by writers who are not yet on their deathbeds.

Strunk and White lead the way. In The Elements of Style they proclaim—simply but resoundingly, as their Rule Number 10—“Use the active voice,” and they press the case for “direct,” “forcible” language. They don’t favor the elimination of all passives; they themselves use the passive construction “can be made lively” on the same page. But their thrust is clear: to promote more writing like their own, which in general has straightforward thrust

Among the many strenuous opponents of the passive voice, a majority—taking their cue from George Orwell, in his essay “Politics and the English Language”—stress how easily that voice can be used to conceal accountability, since it doesn’t call for the person or entity that performs the action of the verb to be named. The passive sentence “The dog hasn’t been walked yet” stops well short of implicating any member of the household as the negligent appointed walker.

One can spot such concealment of responsibility—or, in the lesser case, downplaying of responsibility—in much of the language issued by government offices. It sounds like this:

A secret shipment of arms to the insurgents was requested on March 19, approved on March 20, and carried out on March 21. [That’s at least three different people who owe their anonymity to the passive voice.]

Undeniably, mistakes were made. [Yes, but who made them?]

In the world of medicine, concealment of agency can sound like the following excerpt from a note a surgeon composed in 1961 at the request of comedian Lenny Bruce, for use in the event the heroin needle marks on his arms were noticed by police.

Mr. Bruce suffers from episodes of severe depression and lethargy . . . . He has therefore been instructed in the proper use of intravenous injections of methedrine. [Who instructed Bruce? No one in particular, it seems.]

By contrast to the stance of Strunk and White and Orwell, the grammarian Otto Jespersen takes a downright expansive view of the passive voice and manages to come up with five situations that justify one’s speaking in it. Often, for example, the doer of the deed described in a sentence can’t be identified, and recourse to the passive eliminates the syntactical need to say who it was. In the passive, we can make do with “He was killed in the Boer War.”

Even the broad-minded Jespersen, however, does not see—or, perhaps, sees but does not cite—psychotherapeutic grounds for use of the passive voice. Please bear with me as I blaze a path into that realm.

Consider these two sentences:

active voice

I won the Oscar for Best Actress.

passive voice

I was awarded the Oscar for Best Actress.

Think of all the factors besides talent that influence the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences when they cast ballots for the year’s best actress. A partial list:

- the actor pool they have to select from (Most films produced in a given year get little exposure, even to members of the Academy, and actors in those films are therefore effectively out of the running at Oscar time.)

- likeability or friendship

- envy

- sympathy (especially for older actors who’ve been bypassed for awards)

- box office receipts.

Which of the two formulations, active or passive, reflects more understanding of the whole context in which awards are made? The phrase “I won” seems to reduce a vast, complicated array of factors to just one factor (albeit a big one): talent—or perhaps talent coupled with will and hard work. It seems to say, “This was essentially my doing.” Does the woman who says “I won”—even if her success indeed rests largely on her own talent—grasp her true bearings in relation to the world?

She does not, I think. The woman with true bearings is the second of the two, who, consciously or unconsciously, allows for the support and interplay of all the other elements that contributed to her success and says, “I was awarded.”

But there is even more to say for passivity. In fact, I’m just finally coming to the heart of this chapter: Not only does it take a somewhat passive mindset to see the many things at work on one’s behalf in life besides one’s inborn gifts, but those inborn gifts themselves can’t be tapped without one’s learning to be largely passive in relation to them.

Artists, in particular, have led the way in giving expression to this insight, although it applies to all pursuits I know of.

At a post-performance Q and A session, I once heard puppeteer Eric Bass compellingly describe how, when performing, he “took his lead from” his puppet. And, in fact, his consummate performance had left me wondering who was in charge onstage, Bass himself or his loquacious wooden handful. “Art well concealed,” you may say, but there was more—a profoundly deferential state of mind, an attitude embedded in the phrase “took my lead from.”

Artists of all kinds are hesitant to say that they “produce” their creations. When they don’t call on the passive voice to describe their work—as in such commonplaces as “I was inspired to . . . ” or “gripped by . . . ” or “flooded with . . . ”— they resort to other ways to minimize their part in the process: phraseology like “I took my lead from” and “I felt I was channeling a source I couldn’t name.”

Sculptors who carve marble might be thought to be unlikely advocates of passivity in art. Isn’t hacking into any solid piece of stone—to transform its shape forever— blatantly a case of imposing one’s will on it? As a class, however, sculptors of marble aren’t an exception to the rule.

Michelangelo, in fact, claimed that, in sculpting, he was merely finding forms concealed within his slabs. And Michelangelo’s admirer Auguste Rodin talked of his own sculpture in the same, unmistakably passive spirit:

The work of art is already in the marble. I just chop off the material that isn’t needed.

What these artists have discovered is of crucial importance in all our endeavors, from beautifying women’s hair . . . and selecting jurors for a trial who would view one’s client sympathetically . . . to chicken-sexing (the job of sorting newborn chicks by sex, when the telling organs in question aren’t yet displayed—a task at which the best practitioners can’t say why they are succeeding).

Much of the time, even fighter pilots must rely on unconscious muscle memory, rather than on effortful (and time-consuming) calculation, when flying.

illustration by Juliana Duclos

Does my reader still need assurance that the unconscious can play vital roles in life? Here, then, is more evidence to mull: We never learned consciously—learned, that is, by articulated rules—how to recognize a face or to throw both arms in front of ourselves to break a fall. These skills came to us with being human.

Or, try deciphering this passage:

. . . I cdnuolt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg. Aoccdrnig to a rscheeachr at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are,

the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be in the rghit pclae.

I am guessing you succeeded, but how did you do it? You don’t know. In all likelihood, little intellectual exertion was involved. The correct words came to you by a mechanism beyond consciousness—that same one briefly alluded to in the last sentence of the oddly spelled block quote itself.

And consider what goes into stringing adjectives together like this:

eighty self-important state representatives

or like this:

their big, well-written 2020 travel guide.

You could not have said,

eighty state self-important representatives

or

their well-written big travel 2020 guide

or, worse yet,

big travel 2020 well-written their guide.

Linguists and grammarians have teased out the extremely complicated rules for sequencing adjectives in a series, but you and I and those grammarians themselves mastered those rules without ever being taught them or having them formulated for us. We absorbed them from all the conversations that we heard around us, and the process bypassed consciousness completely. Now, as we talk or poke away at keyboards, they have their way through us.

One reason many of us don’t build much passivity into our activity is that we don’t give the dark unconscious— what Michael Polanyi calls “the tacit dimension”—its full due. In compulsively standing guard against unreason (of course, to some extent we have to be on guard in that direction, since consequential bad decisions periodically descend on us from those same creviced hills in the brain), we deny ourselves access to the region where—alongside unappreciated mundane skills like sequencing adjectives and breaking a fall—many of our best, most valuable resources for creative life reside: instincts and dim memories, unpredictable associations . . . . Too forcible a feeling of “being in charge” somehow drives these into hiding.

In my own case, this discovery occurred in conditions I’d never have predicted for it: I was on a plane flight of about six hours, from Boston to L.A., at an altitude of more than thirty thousand feet. Until that flight, I had little inkling of what my unconscious abilities were. The echoing words of my elementary school principal, “Larry makes up in effort what he lacks in intelligence,” had actually helped convince me at age ten never to trust my spontaneous instincts. I would compensate for meager brains by doing what I knew already how to do quite well: making plans and sticking to them. This itself was a comprehensive plan for life—a plan to go on planning—and its grip on me persisted far too long. I lived too single-mindedly, deliberately, with little “give,” well into my twenties.

Then came those six hours on a jet. I had been trying my hand as a playwright at the time but producing hardly any material that felt stageworthy to me. Then, to my astonishment, in my half-a-dozen airborne hours I turned out more text worth keeping than I had in all the several prior months of work on my project. What conditions had produced such a breakthrough? Once in California, I took walks along the ocean to process my experience. I came to believe two things:

- Being on a moving plane had, strangely enough, relieved me of my constant, proactive wish to be “getting somewhere.” That, by definition, is what I was doing on a plane in motion. I could then relax and, relinquishing control of things in general, take a flight-within-a-flight, as well, aboard my unconscious.

- Means might well exist at ground level, too, for eliciting the state of mind that I enjoyed in flight.

That’s when I began to make a point of saying, in my new, passive voice, “I am being visited by some ideas today, at my desk here,” and “I’ve become absorbed by what a tragic fix my characters are getting into this morning,” and the like.

In my own case—maybe yours, as well, so give it a try— what it mostly takes to tap into the stream of subliminal content is to replace active voice utterance with passive voice at certain moments. For me, that straightforward grammatical move brings generativity.

Also, for good measure, I keep a homemade sign on my desk that (only half-jokingly) reads, “You are being paid to be passive. Get used to it.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

From 1973 to 1983, Lawrence Weinstein taught writing at Harvard University, where he cofounded Harvard’s Writing Center. He then joined the English Department of Bentley University, where he became Director of Bentley’s Expository Writing Program. His books include Writing at the Threshold, a bestseller of the National Council of Teachers of English, Money Changes Everything, and Grammar for a Full Life: How the Ways We Shape a Sentence Can Limit or Enlarge Us.

From 1973 to 1983, Lawrence Weinstein taught writing at Harvard University, where he cofounded Harvard’s Writing Center. He then joined the English Department of Bentley University, where he became Director of Bentley’s Expository Writing Program. His books include Writing at the Threshold, a bestseller of the National Council of Teachers of English, Money Changes Everything, and Grammar for a Full Life: How the Ways We Shape a Sentence Can Limit or Enlarge Us.

Get Unstuck and Live Fully

© 2021 Diana Hill, PhD and Debbie Sorensen, PhD

Excerpted from ACT Daily Journal: How to Get Unstuck and Live Fully with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy by Diana Hill, PhD and Debbie Sorensen, PhD. Reprinted with permission from New Harbinger Publications.

When you are faced with life’s challenges, it’s easy to lose track of what’s important, get stuck in your thoughts and emotions, and become bogged down by day-to-day problems. Even if you’ve made a commitment to live according to your core values, the ‘real-world’ has a way of driving a wedge between you and a deeper, more meaningful life.

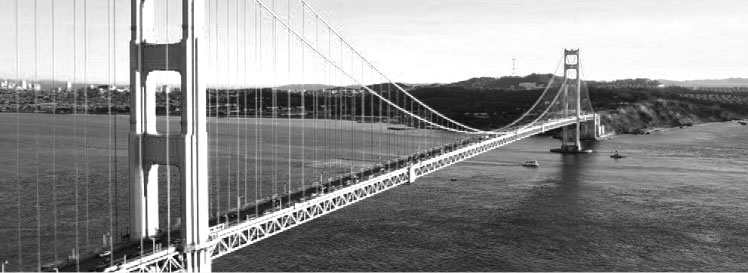

There’s a tale that Diana’s dad used to tell her as a little girl: It takes so long to paint the Golden Gate Bridge that as soon as the job is finished, the painter has to turn around and start all over again.

Have you ever felt like that in your life? Do you keep facing similar problems, get stuck painting the same spots, or get so busy painting you forget to take in the view? Do you struggle against the discomfort of it all or start wondering if you’re cut out for the job? Or do you find yourself painting for endless hours without a sense of why this is even worthwhile or what direction you are heading?

Life can be a lot like painting the Golden Gate Bridge.

To finding meaning on the bridge of your life, it’s important to:

- Have compassion for yourself when you make mistakes

- Pause from time to time and take in the view around you

- Make room for discomfort when things get boring, hard, or scary

- Hold your thoughts lightly when they are discouraging or unhelpful

- Identify the parts of your life that matter most to you, and do your best at those parts

- Look toward the work ahead with a sense of direction and perspective

- Keep at it, day, after day, after day

Psychological Flexibility: The Key to Psychological Health

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a modern, evidence-based approach that offers a different perspective on wellbeing. You might think that therapy is about getting rid of “bad” thoughts and feelings and encouraging more “good” ones. ACT, by contrast, focuses on helping us make room for the uncomfortable thoughts and feelings—because not only are they part of life, but discomfort is inherently linked to the things in our lives that mean the most to us (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2016).

Researchers have shown, through thousands of studies, that ACT skills are not only beneficial if you’re struggling with psychological distress, like depression or anxiety, but also if you want to improve your relationships, develop healthier exercise and eating behaviors, cope better with pain or health conditions, or make pro-social changes in the world (Hayes, 2019).

ACT’s aim is to build your Psychological Flexibility. Psychological Flexibility is the ability to be aware of the thoughts and emotions you’re having at any given moment and be flexible in the face of those thoughts and emotions, even when they are painful, so you can make conscious, values-driven choices, rather than impulsive ones. If you are psychologically flexible, you are less caught up in unhelpful thoughts, more self-accepting, and better able to commit to the behaviors that you want to change (Hayes, 2019). And ultimately, when you’re psychologically flexible, you’re able to keep moving in the direction of the things that really matter to you, even when you encounter challenges along the way.

When you are psychologically flexible, you:

- Are present in the life you have.

- Know what you care about and live in a way that’s consistent with your values.

- Accept and allow discomfort and pain instead of avoiding it.

- Identify and unhook from unhelpful thoughts.

- Connect with an observer self, one that can see your experience from many perspectives.

- Take committed action toward what matters most in your life.

The reality is, experiences of discomfort and pain are embedded in every fulfilling life. You are more likely to experience discomfort when you engage in activities that matter deeply to you. When you are psychologically flexible, you are able to fully engage in your life, even when strong emotions and inevitable problems arise.

Psychological Flexibility looks like:

- Starting a new relationship even if you fear vulnerability.

- Making a change to pursue meaningful work even when it’s intimidating

- Being a caring parent even when your child is pushing your buttons.

- Moving your body even when your mind screams, “I don’t want to!”

- Taking action against racism, social injustice, or climate change even when it’s uncomfortable or exhausting

Psychological flexibility is your heartwood.

In order to build a life that matters to you, it helps to have “heartwood.” In the early 1990s, scientists tried to create a closed ecological system that was self-sustaining called the Biosphere 2. They planted trees. The trees initially grew more rapidly than they do outside of the dome, but then they began to collapse before maturation. Why? Because trees need wind to grow strong and flexible. Wind triggers the tree to build heartwood - wood that is better able to respond the life’s natural stressors.

By opening up fully to all aspects of your experience, clarifying what matters to you, and taking committed action toward your values every day, you will become more resilient and better able to withstand the turbulent winds of life without falling over.

Preparing the Ground

When we are trying to grow and learn something new, we often get in our own way. We might get caught up in criticizing ourselves or others for our mistakes and imperfections. Or we might get so busy making change that we don’t take the time to care for our basic needs. This doesn’t help. When we are hyperfocused on our failures, or neglect our self-care, we are less likely to make progress toward what really matters to us. In fact, there are numerous studies showing that kindness and compassion are key to performance and wellbeing (Neff, 2011). When you focus on compassion, self-care, and intention, you:

- Uncover the critical inner voice that keeps you stuck.

- Cultivate a compassionate inner advisor who can advise you in more helpful ways.

- Learn about your brain’s Threat, Drive, and Caring Systems—which influence the degree to which you’re critical or compassionate.

- Develop simple self-care practices for emotional and physical wellbeing.

- Learn to use your time with intention.

Live in the Now

Throughout the day, our attention is pulled many different directions, and we waste a lot of mental energy worrying about our future or ruminating over our past. When our minds are elsewhere, we lose sight of the moment that’s happening here and now. By becoming more aware of the present moment, you can fully experience your life as it’s unfolding, and make more conscious decisions. When you practice Present Moment Awareness skills, you will:

- Move from living on autopilot to living with intention.

- Savor more moments of your daily life.

- Have greater self-awareness of your body’s sensations, thoughts, and emotions.

- Find a steady center in the face of difficulty.

- Bring more awareness to your relationships and work.

Greet the Monsters in Your Head

One of the biggest barriers to living life effectively is getting stuck in your own head. Unhelpful thinking, like self-criticism, rigid beliefs, and “shoulds” can trip us up, stall us, or make us inflexible in our approach. We don’t have to convince ourselves that these thoughts aren’t true, but rather see them for what they are—thoughts, not truths—and hold them more lightly. In doing so, you learn to:

- Notice your chatty mind.

- Step back and create space from your thoughts.

- Use humor and playfulness to get unstuck from thoughts.

- Let go of trying to control your thoughts.

- Get more flexible with rules, being right, and “shoulds.”

- Practice choosing to pay attention to thoughts that are helpful, not harmful.

Open Up, Allow, and Be Curious

If you reflect on your past, anything you’ve pursued that has mattered deeply to you has involved some degree of discomfort. In order to live with meaning and purpose, you will at times experience emotions, thoughts, and sensations you might rather avoid. The desire to avoid discomfort is understandable, but that inflexibility comes at a price. Psychological Flexibility means opening up to all aspects of your emotional experience, even the unpleasant ones, in order to do the things that matter to you.

By focusing on Acceptance you will:

- Explore the messages you’ve been taught about emotions.

- Recognize the signs of avoidance in your day-to-day life: like numbing out, distracting yourself, opting out of opportunities, or speeding through life.

- Uncover the consequences of avoiding pain and discomfort

- Increase your curiosity and openness to face all of your emotions, thoughts, and sensations, pleasant and unpleasant alike.

Take in the View

The ability to shift perspective is key for empathy, innovation, and positive change. When we are stuck in our self-stories—the story we tell ourselves about who we and others are, what we can and can’t do, and what we deserve—we can miss out on so many life experiences unfolding every day. Perspective taking helps us open the aperture of our lens, take an observer stance, and flexibly shift into seeing a situation from a new point of view. Being able to take on others’ perspectives lies at the heart of compassion, conflict resolution, social justice, and developing a wise mind—a mind that can draw upon the wisdom of both your emotions and your rationality.

When you practice Perspective Taking you will:

- Identify some self-stories that keep you stuck

- Get more flexible in your self-labels and categories

- Broaden your perspective to a “sky mind”, accessing the part of you that notices rather than just the part of you that thinks.

- Explore perspective taking over time

- Use perspective to explore broader possibilities in your life

Choose Your Direction

What brings you meaning, purpose, and vitality in your life? What do you really care about? And what type of person do you want to be? In ACT, values are defined as descriptions of how we engage in the actions that matter to us. They’re the qualities that we want to reflect in our actions: kindness, courage, spontaneity, you name it. Values, unlike emotions or thoughts, offer us a direction that gives meaning and vitality to our lives.

When you practice focusing on Values you will learn to:

- Tell the difference between a pleasure-filled life versus a meaningful one.

- Identify what you want your life motto to be.

- Explore your values within domains that might be important to you, like family, career, community, or spirituality

- Realign with your values when you get off track

- Explore impermanence, as a way to continue determining the values and actions that mean the most to you

Falling on Purpose

Committed Actions are ongoing steps we take in the direction of our values, even when those steps are difficult. Living a values-driven life is a big job. Some days, your progress may seem slow and your motivation may wane. By focusing on getting moving, using principles from behavioral psychology and habit formation that help you stay flexible when change gets hard so you can remain committed, you will learn to:

- Use values to increase your motivation to change.

- Focus on the process of taking action, rather than outcome.

- Develop small habits that are achievable, even when your motivation is low.

- Explore obstacles to changing your behavior.

- Create contexts, consequences, and a team to support the changes you desire.

- Develop a flexible and sustainable action plan.

Flexible Integration

Implementing the processes of self-compassion, mindful awareness, acceptance, willingness, perspective taking, and committed action—ACTing Daily—creates a life you can savor and feel proud of.

Turns out, the story about the Golden Gate Bridge is only a tale; the painters don’t start at one end, paint all the way through, and start over. In reality, a crew of painters works continually to keep the bridge up, doing maintenance as needed. And much like those painters continually working on the bridge, the processes of Psychological Flexibility are lifelong.

We have been practicing ACT for many years, both professionally and personally, and there’s still more for us to learn and practice every day. When the paint starts chipping off, as it inevitably will, ACT can help you to continue to live your values-driven life.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Diana Hill, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice in Santa Barbara, California, where she provides therapy, high performance coaching, and training to mental health professionals in ACT. She is a cohost of the popular podcast, Psychologists Off the Clock, which has over 1 million downloads, where she has interviewed leaders in the field of psychology, mindfulness, and wellness. She is a

regular teacher for the Mindful Hearts Program and Insight LA, and is passionate about integrative health, homesteading, and parenting with intention. She is the co-author with Dr. Debbie Sorenson of ACT Daily Journal: How to Get Unstuck and Live Fully with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Learn more at https://drdianahill.com/.

Diana Hill, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice in Santa Barbara, California, where she provides therapy, high performance coaching, and training to mental health professionals in ACT. She is a cohost of the popular podcast, Psychologists Off the Clock, which has over 1 million downloads, where she has interviewed leaders in the field of psychology, mindfulness, and wellness. She is a

regular teacher for the Mindful Hearts Program and Insight LA, and is passionate about integrative health, homesteading, and parenting with intention. She is the co-author with Dr. Debbie Sorenson of ACT Daily Journal: How to Get Unstuck and Live Fully with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Learn more at https://drdianahill.com/.

Debbie Sorensen, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice in Denver, Colorado, and a part-time Clinical Research Psychologist at the Rocky Mountain VA Medical Center, with a PhD from Harvard University. She cohosts the Psychologists Off the Clock podcast, is co-author with Dr. Diana Hill of

ACT Daily Journal: How to Get Unstuck and Live Fully with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and is a VA Regional Trainer and Training Consultant in ACT. https://www.drdebbiesorensen.com/.

Debbie Sorensen, PhD, is a clinical psychologist in private practice in Denver, Colorado, and a part-time Clinical Research Psychologist at the Rocky Mountain VA Medical Center, with a PhD from Harvard University. She cohosts the Psychologists Off the Clock podcast, is co-author with Dr. Diana Hill of

ACT Daily Journal: How to Get Unstuck and Live Fully with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and is a VA Regional Trainer and Training Consultant in ACT. https://www.drdebbiesorensen.com/.

Roger Rabbit’s Flaming Rear

How I got into Zen’s weird koans

© 2021 Henry Shukman

Excerpt from One Blade of Grass, published by Hodder Yellow Kite, UK, May 2021 (and by Counterpoint in the US).

From the outside, you’d never have known that the modest house in an ordinary suburb was the Oxford Zen Centre. Two rooms had been knocked through to make a zendo from front to back. A sheet of board closed off the fireplace, which backed up against the hearth of the house next door. If you were sitting in the right place at the right time, you could hear the evening news, quietly but clearly, broadcast from the neighbor’s TV.

I liked the center. I would slip in at the back and settle on the nearest cushion before anybody could ask any questions. The customary black mats here were made of foam rather than the usual kapok, softer on the knees, and the small, stiff cushions gave good support. The room was kept in twilight, the shades drawn in daytime, the lamps low at night. The twilight sometimes felt to me as I imagined the Dead Sea would, supporting us as we floated on our cushions.

I began to sense something new here: I’d had a few strange glimpses of what Zen called “awakened nature” over the years, and had become quite attached to them. But they were memories for me. Not a living reality here and now. But when the teacher in this center gave a talk, it was quite clear that he was seeing it here and now. That was different, something I hadn’t felt so clearly before, in other meditation centers I had visited. Something woke up in me and knew it had learning to do. Perhaps I was reconstituted enough now, after a powerful experience of selflessness had suddenly opened me up a few years before, while on a retreat, and after some years of fast-forward careerism that had followed on that, to consider going further down the path.

The Zen group here had been sitting for twenty years, meeting every Thursday evening, and although people came and went there was a core of seasoned meditators, and I was starting to realize what a difference that made. And they didn’t only sit together, but also ran the Prison Phoenix Trust, an organization that brought yoga and meditation into prisons around the country. One of them was a national leader in restorative justice. They were doing their part to build a fairer society.

I’d sit through the rounds of meditation, listen to the teacher’s talk, and always slip out at the end. An urgent need to get away would come over me, fearful lest anything at all – even interaction with other sitters – deter me my new but fragile commitment to practice more deeply.

But one afternoon I came early, and while getting a drink of water happened to run into the teacher in the corridor, and he invited me to join him for tea. We sat at a table by the window in the upstairs kitchen, blowing on our hot mugs. It was sunny outside, and our tea steam lit up in the sunshine from the street.

We talked about how long the group had been going, when they’d bought the center, the work they did in prisons.

I quickly found that John was a nice man to be around. Whatever I might have thought a Zen teacher should look like, he didn’t. A pair of glasses, a handsome, kind face, a mop of mousy English hair: he had been a lawyer most of his career, and now ran two charities for the disabled, and still looked like a regular Englishman.

He asked why I’d been coming, what my interest was in Zen. No teacher had directly asked me that before.

I tried to explain about the retreat I’d done in New Mexico years ago but got muddled. I mentioned some of the centers where I had sat, but that didn’t go right either. I wondered suddenly if I had any idea why I had turned to Zen, or meditation. Then I remembered a stray moment of revelation, an epiphany, that had struck me many years before, as a youth, and said to him: “I guess it really dates back to something that happened many years ago.”

Just then the refrigerator clicked and started to hum

In his stride John said, “The fridge seems to agree with you,” and only then did I realize I had even heard the fridge.

“So what happened?” he asked me.

It turned into a longer conversation, and we settled on cushions in the interview room facing one another. A stick of incense on a simple altar released a straight line of smoke. With the Oxford evening coming on, the light was thick both inside the room and out, over the back gardens of the neighborhood.

I felt good. It was April, spring in the air, and as John and I spoke I felt an unfamiliar sense of possibility. John wanted to know what had happened in that moment on the beach, and also in that other time of deep release from self during a retreat. As I talked, those moments became vivid again, as if John felt them too. I’d never known anything quite like that.

As we talked it turned out he too had had an “opening” in his late teens. He also acknowledged what I had long felt: namely that Zen not only knew about these kinds of experience, but in some sense they were, or could be, central to its training.

John had studied this kind of opening, incorporated it, gone beyond it, forgotten it, and now he was here to help. He knew what to do next. “It’s high time you took up the koans,” he said.

So there was indeed follow-up. Here it was: John was a traditional koan teacher.

Why it took so long to find a teacher able to see where I was coming from, take me in, and start me on the path of training, when Zen is so clear on this process, still baffles me. But that’s how it was. Clearly the student had not been ready, or else the teacher would have appeared.

The following week, when I met with John, he explained that of the two major forms of Zen that had survived, Soto and Rinzai, the latter favored koan training as a means of working with “experiences.” Koans could help to deepen our awareness of the reality we glimpse, and teach us to embody it in our lives.

Exactly what I’d long been seeking.

John also explained that his own teacher had studied in Japan with the abbot of a Zen lineage, a man named Yamada Ko’un Roshi. Yamada used to explain the process of training with a metaphor. Imagine a pane of opaque glass. A hole is driven through it, and suddenly we see that there’s a world on the other side of the glass: that’s “kensho,” a sudden, powerful moment of awakening. Koan study seeks to enlarge the hole, and create new holes, until over time the whole pane becomes riddled with holes, small and large, loses its structural integrity and collapses. Then the separation between that world and this world is gone.

John gave me my first koan there and then, the original ur-koan described by Zen Master Mumon in the 13th century as “the gateless barrier of the Zen sect:”

A monk asked Joshu2 in all earnestness: “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?”

Joshu answered, “Mu.”

I’d heard about this koan in talks given by various teachers in other centers. Literally Mu means “not”. But the real meaning of the koan is something else, something unspeakable.

In the Rinzai sect, the master gives a student a koan and waits to see what happens. The koans are verbal formulations that the student ponders while meditating, said to be impossible to penetrate with the mind: “dark to the mind, radiant to the heart,” they say. The only hope is to give up trying to understand them, and instead let the koan reveal itself to us. Whatever that means.

Mu is traditionally the first koan. The student uses mu as a kind of mantra. On every out-breath, while sitting, they silently voice the sound mu. The student is encouraged not to think about its meaning. The koan has work to do. Its work cannot be done by the conscious mind. Only mu itself can work on the practitioner, releasing them from a kind of prison they didn’t realize they had been caught in. While the conscious mind is kept busy attending to the sound “mu,” the “real” mu can slip in unnoticed through the back door.

It’s funny how it works. The Zen relationship of teacher and student is concerned with one thing: our very existence. As the relationship develops, as the teacher listens to our reports, as our blind spots get exposed, as we feel more keenly their unconditional support, we come to realize they have no agenda of their own.

That’s what I was starting to realize about John. Sometimes he would set aside time to see me in London. We’d meet on a corner near a tube station and go to a café, and discuss some point of practice and its implications, or some new glimmer of understanding that had recently dawned on me.

It’s hard to express how helpful this was. I saw that meditation was not just meditation. It was a means, a vessel, a vehicle. Through daily sitting, through going on periodic retreats at a retreat center on the Berkshire Downs where some three dozen of us would sit with John for a week, it was possible to undergo much more than a calming of the nervous system. In meditation we could pursue the fundamental investigation of a lifetime: the search for our identity.

But a few things had to be in place: a steady daily practice, a life sufficiently in order not to create constant demands on our nerves, a reasonably stable psychology, though the practice itself should help with that, and two final pieces: a community of practitioners, and a guide.

I used to think I shouldn’t need a teacher. I should be able to handle things myself. Wasn’t that the measure of a competent, responsible adult? To the extent you didn’t handle it, life would knock you around until you did. It would teach you the lessons you needed to learn. But it was between you and life. It was a long time before it occurred to me that one of the lessons life had been trying to teach me was that sometimes you needed a teacher.

The point of the teacher, and the community too, was none other than to develop trust. Trust in people. Without trust Zen couldn’t really kick in. Somehow we had to relinquish our hold on our self. I didn’t know I’d been doing this, but for as long as I could remember I’d been gripping onto “me” as to a piece of wreckage on high seas. And this in spite of having seen through “me” in some random unforgettable moments. The Zen teacher allows our grasp to loosen, and one by one encourages our fingers to let go.

In the end we may find we hadn’t been holding onto anything at all, we just thought we had. When we stop holding, all is fine. And then the community shows us what to do next: direct our concern toward others. But it all takes trust. And trusting the teacher in the limited realm of Zen is a first step.

Proust called literature vicarious spirituality. It can’t come close to direct spiritual experience.

Zen does literature too, but in a different way.

Zen is a “mind to mind transmission,” the old ancestor Bodhidharma said. “It doesn’t rely on letters or words.” It can’t be communicated with words, yet can be conveyed person-to-person. That’s why it still exists.

On the other hand, it does deal in narratives of a sort. If a story is fulfilled by a character’s encountering an opportunity for growth, as some scholars say, then a Zen koan is a story. It just happens to be the shortest story of all, and its central character is always us. How to compress a radical shift in worldview into a few words? Koans have mastered that.

They are impossible. A monk asks Joshu, “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?” Joshu answers, “Mu.” End of story.

Some story.

And the teacher says: sit with mu. Just that syllable. No meaning. Breathe it out with every breath, give yourself to it.

How? I don’t know how to, you rail.

No one can find your way but you, says the teacher.

John once explained that sitting with a koan was like a scene from the famous book, Zen in the Art of Archery, in which the Japanese master archer is blindfolded and led into a barn where the shutters have been closed and the lights extinguished. The assistant leaves him to aim blindly at a target at the far end.

The students wait in the dark. They hear two shots strike the target. The second makes a sound different from the first. They turn on the lights. The first arrow is right in the middle of the bull’s-eye, and the second arrow has split the first in two. Koans are like that but more so. Not just: where is the target, but what is the target? How are we supposed to aim for something we can’t even identify, let alone locate?

They allow only one path: be still and give in.

There’s a native American saying: if you’re lost in the forest, the forest knows where you are; be still and wait for it to show you. The koan wants to show itself to us. But it has to be that way round. We can’t go to it, it must come to us.

Koans require patience, even a kind of surrender beyond patience. For a restless wanderer such as I was, koan study wouldn’t seem an obvious fit. Yet it was. Yamada Ko’un wrote that we are like billiard balls: it doesn’t matter what colour a ball is, if struck a certain way it will travel in a certain direction. Like Zen: whether we’re rich or poor, young or old, sharp or dull, healthy-minded or sick-souled, put us in certain conditions, namely on a Zen cushion with a specific koan, and things will happen.

I remember walking into the zendo once during a retreat with John and it occurring to me that my priorities could change. I could make Zen a higher priority. It was nice to consider that. Somehow I had always done it with just a little secret reluctance. I could let that go now.

And my wife was in favor of it. When I went on retreats three or four times a year, she would take our two young boys to her parents. It didn’t seem to conflict with the priorities of family and work. At last I was finding the training I’d sought. Zen’s demands were few: daily sitting, occasional retreats, and being open to what life brought in each moment. It had benefits for others: it made you more attentive, less fretful. It opened up more love, and I’d return from the retreats with vivid eagerness to be with the family.

At the retreat center where John led his retreats, the nuns had their graveyard in a clearing among hazel trees — a circle of tiny gravestones of a sort you might see used for a beloved pet. You could easily miss them when the grass was long.

I remember one of the early retreats I did. It was late February. The trees were bare but you could already see new buds forming on their twigs. During some outside walking I wandered into the grove and thought to myself: in another six weeks the buds will have opened and young leaves will emerge. In another six months those same leaves will be yellow and wilting, and will fall. Like these generations of nuns buried here, who lived, served and died. How foolish if one leaf started admiring itself, thinking it was special, had a destiny unlike the others, it was “chosen” for special treatment. No matter what it thought, the frosts would come and it would go the way of all leaves.

How hard it was then to realize the same was true of me. Somehow, I still held some lurking belief that I was a bit special. But, of course, the seasons and years would roll around and I would end up like these humble nuns, whom no one outside the order had ever heard of. They had known they were leaves on a tree, and that what made them precious was not some imaginary separateness, but being an essential part of the whole life of the tree.

Something was starting to shift in me. Some deeper glacier of isolation and selfishness was starting to melt, to slide off the mountain, down a valley toward the sea.

*

It’s evening. In the boatyard behind our house the tools have gone silent, the workers gone home for the day. Canal boats stand at odd angles propped on breeze blocks, their hulls burnished by grinding tools. There are oil drums, hoses, toolboxes strewn around the yard, and dustbins. Some of the boats have flowerboxes on their roofs, like camper vans being serviced while still full of a family’s belongings. One has a bike on its roof.

I know this because I’ve been gazing out the window. Beyond the yard the late sun pours through a stand of elms in a smoky stream. It’s the tail end of summer.

I’ve been making supper for my wife and myself. The boys ate earlier. I carry two plates of food upstairs. In the little bedroom Clare lies sprawled on the bed with the boys, watching the movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.”

The room is suffused with the last of the sunlight. I bend down to give her a plate, fork balanced on the rim.

“Thank you,” she says.

I stand up straight for a moment, my own plate in hand. I’m about to sit down but get arrested by a scene in the movie where Roger Rabbit’s tail is singed on a stove, and he proceeds to accelerate faster and faster round a kitchen, trying to outrun his flaming rear, turning the kitchen cabinets into a centrifuge like a biker on the Wall of Death.

I remember loving this scene years ago when the movie first came out. I start laughing. Something happens. A tingling, whirring inside me. I notice how malleable the apparently solid surfaces in the cartoon are. The tingle becomes a flywheel in my belly, spinning faster and faster, until it is almost unbearable, a sweet agony. It’s in my chest now, and at once my heart just about breaks, and the sensation whips itself into a cyclone, a dust-devil, a whirlwind, and spins up the throat into the skull.

My head explodes. A thunderbolt hits the room. I black out – except I don’t, I’m still standing. Everything else blacks out. All the circuitry that keeps the world going snaps off. A fuse blows. I find I’m not standing on anything. Below, a chasm; above, a void; all around, in every direction, nothing. Dark radiant nothing.

I let out a whoop and start laughing.

Clare looks up from the bed. “Oh God,” she groans, “It’s not that Zen again.”

Stevie, five years old, looks up at me, eyes huge, clear, brown, luminous as marbles, and asks: “Daddy, what’s ‘growing old’?”

I don’t know where this question comes from, maybe he heard a line about it in the movie. I stare back into his eyes, which are alive like I’ve never seen before. Perhaps I’d never noticed. Without thinking I lean down and say, “There is no growing old, there’s just being alive.”

We stare at one another, and his face blossoms into a grin as he says: “I’m being alive.”

“Yes, you are,” I agree, and we both laugh.

I’ve been working with the koan mu ever since that first dokusan with John. During a recent meeting, he told me: “I want you to start asking yourself, what is mu?”

I’ve been doing this assiduously, while riding my bike up to my office at Oxford Brookes University, while walking around town. The question “What is mu?” has started to feel like a broader question, as if it’s also asking: what is the street, the house, the bicycle, the rain.

A few weeks ago, while riding home through the drizzle, I suddenly thought to myself: this biking through the rain, getting damp – I think I don’t like it. But what if it’s OK, fine, it’s just what it is? Who is it saying it’s not good? For a moment I sensed that all was perfect just as it was.

And a few days ago I found myself wondering: what if there’s a mind that creates the experience of being alive, and even creates my own mind, the mind with which I apprehend things – the road, the cars, the trees? What if it’s all one mind?

Somehow what’s going on right now, with Roger Rabbit and his centrifuge, and the abyss that has opened up, is connected to that question.

Yet this thunder-clap is outside all calculation. There’s just empty sky in every direction. “Not one speck of cloud to mar the view,” an old Zen saying has it. Not one thought in the whole universe. Nothing exists! All this earnest training of the mind that we did in Zen – or thought we did – and there was no mind!

In the room, everything is bathed in rich light, a dark lucent limpidity drenching the bed, the window, the TV, the three other people sprawled on it.

Giddy, dizzy, I totter downstairs with my untouched plate, delirious with joy, feeling like any moment I might topple into the abyss and not caring. How is it even possible to take a step, to be suspended on this imaginary surface called the floor? It’s all a dream, a floating illusion, a mirage-like reflection, a ghost of something on nothing.

The food looks magnificent on my plate, like a still life from a seventeenth-century master. I can’t imagine what to do except admire it. I can’t imagine what to do at all. Everything is one glorious abyss of peace that fizzes with energy.

I pull a cushion off the sofa, fold it in half, and sit down in meditation. I can’t think what else to do. At the end of twenty minutes, the carpet, sofa and cushions are all still alive with energy.

A flicker of alarm: am I going mad? Will this never end?

I let myself out and go for a walk around the dusky neighborhood. Billows of smoky energy seethe everywhere. The houses hang still and quiet in the grey-blue dusk. They too are smoky and alive, poised between being there and not being there. The mind is a wisp of smoke, the remains of a blown-out candle. Not just the houses but the seeing of the houses is the same: there and not there. I could go up and knock on their doors, tap on their windows, but “being there” isn’t what it seems. The world “out there” is a reflection quivering on nothing, even when you rap on a door.

It’s as if everything is answered and fulfilled.

I still can’t put into words what it was – indeed, words were one of the principal devices for screening this reality – but when you saw it, when it appeared, it folded up everyday reality like a piece of paper and dropped it in a furnace. This reality, unbearably real, loved us fiercely, it loved all things, it was like discovering the whole world was one heart. Yet at the same time it wasn’t anything.

Later I heard John quote an old master, Tahui (“Da-way”), from 11th century China, who said that Zen’s reality was a hot stove, and all phenomena were snowflakes which melted when they came near it.

Was that true? Was reality like that? Or was this some kind of madness? Was I being misled by John, and by Zen? But then why was I feeling so blessed, so true, so alright?

I had no answers. Only what I felt. Which was that by some miraculous power I had just been granted a glimpse into reality, into the true fabric of the universe – into its DNA, as it were, and what I had seen there implicated me too, so that it was clear that like everything else, I was a child of the universe. I wasn’t separate from it.

And all without any god. So good was this universe, intrinsically and unto itself, that no god was needed. Nothing extra at all was needed.

*

I was dying to see John, and went as soon as he was next available.

I told him what had happened. He diagnosed it as a “clear but not deep” experience. I was delighted. He seemed to understand every last detail of what I described, and I bowed my forehead spontaneously to the floor in a wave of gratitude such as I couldn’t remember ever feeling. I never wanted to get up. He knew. He recognized it. He understood. That was all I needed.

Then he started plying me with odd questions about the koan mu. They seemed like nonsense, yet I found responses stirring in me, and when I let them out, John would smile at my ridiculousness and agree, and tell me that I had just given one of the traditional answers. I had never known anything like this, in Zen or anywhere else. So the experience had not been random. It actually had something directly to do with mu. This was what a koan was for: to bring about a radical shift in experience. The koan could offer access to an incredible new experience of the world, free of all calculation, all understanding. But more than that, I was discovering that the koan could allow you to meet: the student could come to the teacher with their “experience” and have it met. And they themselves could be met, right in the midst of what they had awakened to.

After a number of interviews like this over the following weeks, John gave me a new koan, the famous one: “You know the sound of two hands clapping; what is the sound of one hand?” It was the best thing: a way of not just confirming and growing confident in the experience, but sharing it. It was what I had been crying out for, for decades: to meet someone in this reality. This was the magic of the koans. They didn’t just open us up, they offered a way to the most intimate kind of meeting.

But it went even further: an authentic koan teacher could lead you deeper. Only through the meeting, the sharing, the guidance, was there hope of integrating the experience, and living it out in an ordinary life, in kindness, in concern not for self but for others.

I remember seeing a cartoon in which planet earth is filthy, churning out smoke, fizzing, simmering unhealthily. God and an archangel are bending over the globe, scratching their heads.

The archangel asks God: “Have you tried turning it off then on again?”

This was like that. The whole world turned off: gone, like a conjuring trick. One flourish of Zen’s robe, and it all disappeared. Instead, a scintillating darkness, a radiant dark – vast, limitless, totally empty.

But why should it be such a deeply happy experience, for things to disappear?

Perhaps because the “void” is intrinsically marvelous. Or perhaps because it’s the way this reality we know actually is, and to be somehow closer to it makes us happier.

So I make an assertion like that, and why should anyone listen? They shouldn’t. Instead, you either throw this book across the room or else one day go and find a teacher, learn to meditate, perhaps pick up a koan and see what happens. That’s the traditional advice: it’s about personal experience, our own, not anyone else’s.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Henry Shukman is a teacher of Zen and mindfulness based at Mountain Cloud Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Henry Shukman is a teacher of Zen and mindfulness based at Mountain Cloud Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

He has been a writer and poet for many years, and his latest book is

One Blade of Grass: Finding the Old Road of the Heart.

Skillful Means: Art Therapy

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Art Therapy

Purpose/Effects

Immersing into the art process allows us to enter a meditative state where relaxation and unconscious expression can thrive. Whether the artwork is a light-hearted reflection or a deep focused exploration, the benefits can be significant. Releasing emotions and thoughts through a creative force can relieve stress; encourage problem solving; and heighten our senses; though it can also bring up some rough memories. Art is a safe, controlled way to manage our life experiences, which we may not get to do in other ways.

Method

Summary

Select an art form and use it to express yourself however you see fit. Keep in mind that your primary intention should be for exploration and experimentation free from a sense of what it “should” look like. A lot of our anxiety about expressing ourselves has to do with this desire for approval that may go back as far as wondering why our parents never put our artwork on the fridge door. Try to separate how you think of the art in museums versus the art we create every day in order to express ourselves.

Follow your own intuition about how to proceed, when to add to your work and when to stop.

Also, try to avoid overanalyzing the meaning of your work if it feels forced, inorganic, or if it’s causing you more stress than before you began. This may be an opportunity to seek guidance from a professional, though sometimes the art doesn’t “have” to have a meaning.

Long Version

- Do something you like. If you find painting appealing, you can explore with various colors or applications of paints to your canvas. If you are a very tactile person, you may enjoy working with clay in order to express your emotions. Scrapbooking and collage can be an effective way to enhance or deepen a connection to a memory, since you can use universal materials such as magazines to make a personal creation.

- Think about colors. What colors make you think about yourself and your life? Which colors reflect your moods and your emotions? You could use a body outline and depict feelings and sensations abstractly.

- Think about shapes and objects. Does a certain image stick in your head; for example, do you feel like part of a broken circle of trust, or perhaps do you find the light of a candle in the dark inspiring? Use these images to express your feelings through your art; they can be as abstract or as concrete as you like.

- Often the symbols in our dreams can be rich fodder for our creative impulses.

- Try a random scribble for a few seconds and see if any images develop for you.

HISTORY

Art has long been a form of expression to validate existence and make sense of the world. Every generation in every culture offers clues into how art is crucial to document, communicate, and make sense of shared values, experiences, and norms.

To go the extra mile, art making is the lynchpin process in a particular field of mental health. Art Therapy is a world recognized profession that developed and flourished in both Europe and the United States during the early and mid 1900s. Many artists recognized the value in the creative process and began volunteering and working in hospitals to encourage patients to be active participants in their own treatment. Art Therapy has gained exponential recognition worldwide as being a holistic and alternative treatment in light of global tragedies, such as Hurricane Katrina, the earthquake in Haiti, and with our returning veterans suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

CAUTIONS

Remember, art making isn't about being the next Da Vinci or Picasso. The point is to express yourself; worrying about your skills will only hold you back.

Also, if you feel you need additional guidance in overcoming life struggles, it is important to seek professional assistance that best fits your needs.

NOTES

This article mentions the profession of Art Therapy, and it is important to note that while art-making is not a proprietary technique, Art Therapy differs in that it is a credentialed profession that requires Master’s level education, training and supervision for someone to be legally considered an Art Therapist.

If you are interested in Art Therapy either as a service or career, you should consult with a legitimate resource. The American Art Therapy Association provides guidelines and information about the profession and the education requirements for programs, and oversees the work of the State chapters. Also, the Art Therapy Credentials Board oversees and maintains the credentials earned from post-graduate supervision and passing a certification exam.

Last, there are other creative modalities that have engendered credentialed professionals to assist clients with healing. These include Dance Movement Therapy, Music Therapy, and Psychodrama Therapy. Please see all external links below for more information.

SEE ALSO

Chanting / Devotional Singing

Emotional Journaling

EXTERNAL LINKS

American Art Therapy Association (www.arttherapy.org)

Art Therapy Credentials Board (www.atcb.org)

National Coalition of Creative Arts Therapies (www.nccata.org)

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.