News and Tools for Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 18,2• April 2024

In This Issue

Live for The Questions

© 2024 Jeff Karp, PhD

Those moments in our lives when a new question rises up in us, stops us in our tracks, are pivot points. They are openings for discovery and new possibility to break in.

—KRISTA TIPPETT, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR; FOUNDER, ON BEING PROJECT

Several years ago, I found myself thinking about salamanders, and specifically about their tails. When a salamander loses its tail, it grows back within just a few weeks. Many other animals possess this ability: starfish and octopi can regrow their arms, zebrafish can regenerate their fins and hearts.

It made me wonder: Can we trigger the same response in humans? That question led me, my primary mentor, Robert Langer, and one of our mentees, Xiaolei Yin, on a multiyear quest for an answer. One of the answers led to a potential treatment for multiple sclerosis (MS) by activating the body’s regenerative potential. The treatment is now advancing through clinical trials and has promise for many applications.

Research and innovation in the lab are most often rooted in solutions suggested by some aspect of the natural world. Nature is a touchstone in our creative process, and the uplift of energy powers us not only to find answers but also, and first, to generate fresh questions. We observe and inquire. We learned that porcupine quills can easily penetrate into tissue but are difficult to remove. How could that knowledge help us design better surgical staples? What allows spiders to walk on their webs without getting stuck while their prey is fatally trapped, and how can that understanding help us design medical tape that will adhere to a newborn’s tender skin but can be removed without pain? Nature has answers to questions we haven’t even learned to ask yet. Evolution has created a vast range of tough, long-surviving capabilities that often point the way to medical progress for us human beings. It’s up to us to dig, but first we must determine the questions that can define the problem to be solved and lead us to the answers we seek.

We’ve learned in the lab that in the high-stakes world of innovation there needs to be a lot more emphasis on questions than on answers. Every success and failure we’ve had can be traced back to the questions we asked, or didn’t ask, earlier in the process.

One of the most notable setbacks I ever had in my professional life turned on a question we’d never thought to ask. It was in a seminal moment early in the launch of the lab with a new technology we developed. We thought the technology had the potential to transform medical treatment for a host of diseases and improve quality of life for millions of people around the globe. The project deadended abruptly one afternoon when I met with a potential investor.

In brief, stem cells were infused into a patient’s bloodstream. The cells would be programmed to travel to specific sites around the body to treat such conditions as inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, or osteoporosis. But the prospective investor pointed out that the therapy was “too complicated” to fund. Our team had not even considered what would have to happen to bring our ideas into the medical marketplace. It was the question none of us had asked: How will this treatment reach patients? The science was exciting, but we’d never considered how to move it into clinical use.

In that uniquely specific task, moving medical science into practical application, everything rides on the quality of the questions we ask to define and solve a problem. That includes the scope of those questions, as we learned. And sometimes you can follow a promising path, asking all the pressing questions, only to meet the challenge of “the missing piece” that becomes apparent only when, for instance, a clinical trial fails because a piece of basic research, often related to human biology, has yet to be discovered.

We were disappointed that our stem cell−targeting idea failed to secure funding because it was too complex. But we had it in our power to see that our solutions wouldn’t dead-end that way again. Moving forward, we wouldn’t just assume that somebody out there would determine how to manufacture, package, and distribute a therapy. We would investigate it—own every part of the problem to be solved—and bring in new lab partners with the needed areas of expertise to solve the bench- to-bedside challenge together. We would ask more and better questions.

To ask the hard question is simple.

—W. H. AUDEN

Questions—some of them intentionally random—became part of our exploratory process with physicians, scientists, and others as we researched every facet of a problem we set out to solve. That meant conducting layers of exploratory inquiry to investigate the clinical problem, the science problem, the patent problem, the manufacturing problem, the regulatory problem, the practical use problem, the investment problem, and the go-to-market problem. I’m always looking for usable information, the kind of practical knowledge that you won’t find in a research paper or textbook. I also question my questions: Why am I asking this question? Where does it lead? What might we be missing? In problem solving, there are so many different angles that can be explored, and the majority of them will lead to a dead end. The questioning itself becomes a sleuthing exercise, the questions tools to try to generate unique insights that will lead to a solution.

After the investor dashed our hopes for the stem cell therapy, I had to ask myself why I had overlooked the steps needed for implementation, which now seemed obvious. The reason was that throughout its history, academic research has focused mainly on basic science. Researchers generally lack formal training in how to use their findings to make and distribute products. They typically know little about patents, regulatory steps, manufacturing processes, trials, and patient-related needs. In those early days, I was no exception. Today, these questions are as central to the lab’s process as the therapeutic approaches we develop.

The takeaway for any of us in any circumstance is to challenge ourselves to think beyond—to understand the unquestioned assumptions and beliefs that may be limiting our thinking. You don’t have to prove them wrong; just question them to dig deeper and search further. Rigorous questions are at the heart of scientific inquiry, but you don’t have to be a scientist to love asking questions and cultivating them in everyday ways. Questions of curiosity. Problem-solving questions. Basic skills questions. Questions about our purpose as human beings and the meaning of life.

Questions are like excavation equipment: versatile tools for action. Questions can cut like a backhoe through old assumptions, or like an archaeologist’s trowel and brush that uncover buried artifacts or gems, or like the sculptor’s chisel that releases a masterpiece from a slab of marble. Or think of a Swiss Army knife, the everything tool: a sharp question can pry the lid open on a conversation, cut to the core of a matter, tighten the screws of a loose concept. You can use a question to accelerate a conversation or slow it down to allow time for reflection. I like to think of lit questions in the larger sense as fire starters, lowering activation energy and generating the spark for dialogue, exploration, critical and creative thinking, and curiosity. These metaphors are excessive, perhaps, but the point is to underscore this aspect of questions as tools for action, much as we think of other tools as having power and purpose.

Questioning takes the familiar and makes it mysterious again, thus removing the comfort of “knowing.”

—JULIA BRODSKY, EDUCATOR AND EDUCATION RESEARCHER

Are You Ready to Question Your Own Process?

Decisions we made in the past still influence us, and too often we accept them without questioning whether they still apply. We get confused by what the possibilities are and what we think is possible based on our experiences and environment at the present moment. So, we need to question not only our current assumptions but also how these might stem from a historical assumption that bears reexamination.

In the lab, for example, in 2014 we published a highly cited opinion piece in the journal Nature Biotechnology in which we reported that an assumption associated with a particular type of stem cell was wrong; that stem cell type had been assumed to have no innate immune response when transplanted from one person to another. But we had found data in the literature that refuted the point. So, we dug into the question and found conference presentations from years before when this assumption had been imprinted into the scientific literature.

What do we accept as true that may be based on an inaccurate or now-outdated historical precedent? What are we doing in this moment that is constrained by a factor we can remove by questioning its assumptions?

We’re born curious, and asking “Why?” comes naturally; just listen to any preschooler. But the skill to craft a stimulating, strategic question is not innate. It can be learned, and it’s something like an extreme sport for the brain, both challenging and exhilarating. The more you work with your own process, the more you will develop the skills and the confidence to question.

One technique is to study how people you admire ask useful questions. What part of their approach could you adapt for yourself? For me, asking that transformed my life. Early in my college career, I was determined to overcome my childhood struggle to master some basic academic skills. I wanted to ask better questions. To learn how to do so, I did something very geeky: I started to write down all the questions people asked at the end of lectures, looking for patterns. I found a few important ones. I’ll stick to the scientific example, but each of these main points is applicable to any context. The best questions—the high- yield ones—arose when they drilled down in these ways:

-

They illuminated important assumptions that were made without substantial support. Scientists in training often will assume that the methodology they are using, which they read on a company website or in someone else’s work, should work if they follow the procedures, so they don’t check to see if it really works before they try it in their own experiment. I realized that it is important to ask initial questions, such as “How do you know your assay or the kit you’re using is actually working properly?”

-

They exposed flaws or distortions. In science, this might include overstated conclusions, alternate conclusions, and missing control groups that, if included, might have narrowed the interpretation of the results—for example, when researchers perform experiments in salt water (buffered saline), get a great result, and make a strong, broad conclusion but don’t test in more complex biological fluids that contain lots of proteins, which could change the answer.

-

They challenged how we monitor progress, make decisions, and identify issues and opportunities. Sometimes researchers use the wrong statistics to compare things, which biases whether a result is statistically different or not. Often when we use the wrong statistical approach, we may find a difference between two groups that does not actually exist!

-

They distinguished between results that were interesting and results that mattered. In other words, they distinguished between those considered interesting because they showed a difference, and those that are important because the difference could matter to a patient or to potential applications beyond what was envisioned. A difference may be interesting, but a difference that matters—that’s what all of us want.

That awareness helped me learn to develop questions that dive toward the target, whether satisfying my own curiosity or finding the best solution to a problem. It also made me determined to create an environment for others, eventually in my own lab, where we resist the rush for answers and solutions and instead press ourselves to ask better questions. Our major quest is to define the problem we aim to solve and the highest possible measure of success—which we then aim to exceed.

In the lab, one of the most important questions is “What bar do we need to exceed to get people excited?” In other words, what’s the best result anyone has ever achieved, and how much further must we go to make a significant positive impact? What’s the threshold for impact we must surpass? This is hard to define because it requires having a detailed understanding of the best results achieved by others.

I always remember what my mentor, Bob Langer, said about high-yield questions: it takes just as much time to work on an important problem as on a less pressing problem. Whether we succeed depends on the questions we ask that define the problems we want to solve. The better the questions asked, the greater the potential to make new and impactful discoveries.

Inquiry turned inward

The questions we ask hold the power for change, whether in a lab or in your life. Inquiry turned inward, the examined life, has us consciously explore what is most meaningful to us and how to live aligned with those values. Because our lives are ultimately intertwined with all others and within the natural world as a shared habitat, the questions we ask can begin to shape our desire to serve life beyond ourselves alone.

As a practical matter, self-inquiry helps us recognize the rhythms and dimensions that are part of our biological nature and at the same time figure out how we can experiment to adapt, change our mindset, evolve our perceptions to better serve us. It’s a lifelong practice. There is no discrete atomic truth about anything, just layers upon layers of fractals and interconnections that may be revealed over time—or you can just get on with the dig. Asking questions helps us figure out what we like about where we are—wherever we may be on life’s continuum—and what we’d like to change or see evolve. The more we interact with others, hear diverse voices and perspectives, and listen to our own mind, the better we’ll be able to question and evolve with intention.

We seek meaning in life and in our work, and the questions we ask ourselves can open fresh ways to think about that: What is meaningful in the moment? What’s meaningful today but might change over time? What is meaningful in a more lasting way? Engaging in a process for self-inquiry helped me learn more about myself. I was able to examine my priorities and shift my attention to my relationships, especially with my family, to understand what was most fulfilling at its core. When I recognized the deep well of energy, comfort, or peace of mind that my family is to me, it deepened my sense of purpose.

If you never question things, your life ends up being limited by other people’s imaginations. Take the time to think and dream, to question and reconsider. It is better to be limited by what you can dream for yourself than by where you fit in someone else’s dream.

—JAMES CLEAR, ATOMIC HABITS

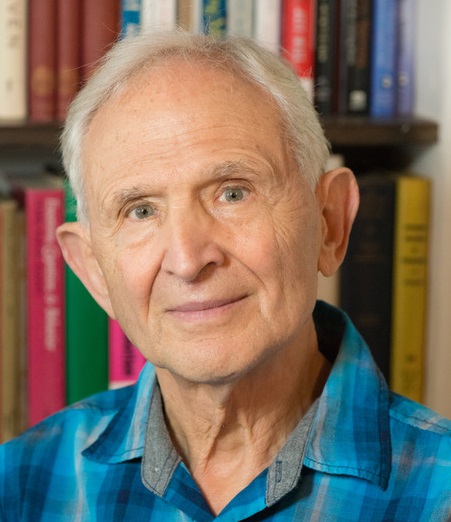

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Karp, PhD is a passionate mentor and biomedical engineering

professor at Harvard Medical School and MIT, a Distinguished Chair

at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and is a fellow of the National

Academy of Inventors. His lab’s technologies have led to the formation

of thirteen companies. The technologies they have developed include

a tissue glue that can seal holes inside a beating heart; targeted

therapy for osteoarthritis, Crohn’s disease, and brain disorders; “smart

needles” that automatically stop when they reach their target; a nasal

spray that neutralizes pathogens; and immunotherapy approaches to annihilate cancer.

Jeff Karp, PhD is a passionate mentor and biomedical engineering

professor at Harvard Medical School and MIT, a Distinguished Chair

at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and is a fellow of the National

Academy of Inventors. His lab’s technologies have led to the formation

of thirteen companies. The technologies they have developed include

a tissue glue that can seal holes inside a beating heart; targeted

therapy for osteoarthritis, Crohn’s disease, and brain disorders; “smart

needles” that automatically stop when they reach their target; a nasal

spray that neutralizes pathogens; and immunotherapy approaches to annihilate cancer.

Growing up in rural Canada he was written off by his school because of ADHD and learning differences. He evolved a process for embracing life, embodied by a set of 12 simple holistic tools developed over years of iteration and tinkering to make his unique patterns of thought and behavior work for him. These tools are now the subject of a new book: LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature’s Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite Action.

Jeff is also Head of Innovation at Geoversity, Nature’s University, a rainforest bio-leadership training conservancy located in one of the top biodiversity hotspots in the world. Dr. Karp lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, with his wife, children, and two Cavalier King Charles spaniels.

For You

© 2024 Tom Bowlin

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Bowlin writes about what life is like for us, what’s been done to us,

what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost

his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the

hard times we all experience. His poems don’t always reflect his personal

beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about “us.” His two poetry

books are Us and Love and Loss .

Tom Bowlin writes about what life is like for us, what’s been done to us,

what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost

his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the

hard times we all experience. His poems don’t always reflect his personal

beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about “us.” His two poetry

books are Us and Love and Loss .

Sovereignty

© 2023 Emma Seppälä, PhD

Excerpted with permission from Soverign: Reclaim Your Freedom, Energy & Power in a time of Distraction, Uncertainty and Chaos by Emma Seppälä (Hay House, 2024).

Sovereignty is internal freedom and a relationship with yourself so profoundly life-supportive and energizing that it allows you to access your fullest potential. The fullest potential you were born for.

Trust me, you’ve felt it. You’ve felt the sovereignty fire, kindled, in the pit of your stomach at different times in your life.

It’s the inner flame that lifted you up from rock bottom and kept you walking through the darkest of nights. It’s the roar of defiance that helped you back to your feet every time you were knocked down—a declaration of your fight and right to live as you, no matter what. It is what has kept you alive despite everything.

Regardless of our race, nationality, religion, gender, or social status, we are, at our core, the same: sovereign. We all have the same desire to live in the fullest expression of ourselves.

Sovereignty allows us to reclaim the treasure trove of possibility that exists within all of us, if we allow it.

Sovereignty is your birthright.

And somewhere deep down, you know it.

Take the example of Maya, who was born into a working-class family riddled with addiction in rural Indiana. She grew up in a trailer and suffered abuse as a child. She felt pride in herself for the first time in her life when she joined the Indiana National Guard. She identified with the values of service, commitment, and camaraderie, and began to feel hope for her life. That is, until she deployed to Iraq. She was in combat operations during the day—with all the hellishness that entails—and at night, her very own commander, a member of her community in Indiana, sexually assaulted her and prostituted her at gunpoint to her own colleagues. If she ever said anything, her commander threatened, she would not live to see the baby she had left back home in the U.S. A modern-day experience of enslavement at the tender age of 22.

Maya was a participant in one of the studies my colleagues and I ran, and she is a woman I will never forget. She stunned me because—despite it all—she was sovereign. She said that our research intervention helped with her PTSD and that she would otherwise most likely have become an alcoholic. But she also had a powerful flame coursing through her veins that you could see in the gleam of her beautiful eyes: sovereignty. Despite everything she had been through, she was determined to show up as a great mother for her son—with all the extra care and love needed for a child on the autism spectrum. She was also a kind and compassionate leader in her community. She went on to beat all odds as a successful high-level leader at one of the country’s top tech companies.

Another example is Nasreen Sheikh. Born into poverty and undocumented in India in the early 90’s, she was forced to labor in sweat shops under abusive conditions in Kathmandu from the age of 10. Yet, at 16, Nasreen defied all odds by becoming a world-renowned human rights activist and successful social entrepreneur to help other women who had suffered the way she had.

Extraordinary people like Maya and Nasreen, who have thrived despite enduring tremendous hardships, exemplify the profound resilience and potential within us all, regardless of our past experiences.

There are many historical examples of sovereignty. Take Diogenes, the Greek philosopher who, after being captured and enslaved by pirates, was being sold as a slave in a busy marketplace when he pointed to someone and cried out: “Sell me to this man; he needs a master.” Or the Buddhist monk who, despite being beaten down, repeatedly sat back up in perfect meditation until his abusers fell at his feet in astonishment and devotion. Or Dandamis, a famous yogi of Alexander the Great’s time, who when threatened with death if he didn’t come meet Alexander, remained unperturbed and unmoving, stating he had no fear of death.1 It’s exemplified in Joan of Arc, a 17-year-old illiterate peasant girl with neither status nor education who rekindled the deadened spirit of an army of downtrodden and unruly French men, turning them into victorious conquerors. And in the enslaved Africans of South Carolina who – after the famous 1739 Stono Rebellion – had their instruments taken away from them yet still kept singing, dancing, and celebrating using their feet and hands, originating step2 and tap dancing.3

These examples and so many others awaken in us a distant memory: the knowledge that the human

spirit is a force to be reckoned with.

Because you can shackle someone and take the instruments away from them, but you can never

take the song out of their soul.

You can’t restrain the human spirit. The human spirit is indomitable. It is sovereign.

Sovereignty is your song. To quote Gurudev Sri Sri Ravi Shankar:

There is a song deep inside you. You are born to sing a song and you are preparing. You are on stage

holding a mic but you are forgetting to sing, you are keeping silent. ‘Til that time you will be restless, until

you can sing that song which you have come on the stage to sing. It doesn’t matter if you feel a little out

of tune for a minute or two. Go ahead! Sing!”

We/you were born for this; born to be sovereign.

The Bound State

Yet sovereignty often feels far from what we experience daily.

To the contrary, we tend to live in what I’ll call a bound state in which, through life experiences, fear, and trauma, we start to disconnect from ourselves. We’re dealing with distraction, uncertainty, and chaos on a daily basis. We are prone to fear and easily influenced by outside forces.

The crises the world has been facing—from pandemics to senseless wars and environmental catastrophes—have dramatically increased mental health problems and sent us further into a state of languishing. The constant barrage of all sorts of news, media, and messaging accelerated by technology and influenced by corporate greed and divisiveness only exacerbate matters.

Research tells us that over 50 percent of people across industries are burned out, uninterested (engagement levels are very low at 34 percent, according to Gallup), overwhelmed, and down. Something feels like it’s missing. Something is lost. Something is not quite right. But we can’t quite put our finger on what it is.

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdown was the first time many of us consciously experienced a sense of being bound: total lack of control, autonomy, and freedom.

Though that time is now behind us, we have experienced living in a bound state far longer than that. A type of invisible lockdown. So old, and so common, in fact, that we fail to see it. So normal, that we don’t even know it’s there.

We’re bound to destructive beliefs, habits, patterns, concepts, relationships, addictions, and misconceptions. It is the reason so many of us feel there is more to life. That life feels empty. It is the reason so many suffer from anxiety, depression, addiction, fear, burnout, and unhappiness.4

It’s easy not to be aware of something when you’re in it, just like the proverbial story of the fish that doesn’t know it’s in water because it has never experienced anything else.

Almost everyone is bound to something. Because it is the norm. It’s social conditioning. It is what we have learned, what we have integrated, and what we have carried with us for generations. It’s deeply entrenched in our own minds. And it is keeping us from living our freest, boldest, and most authentic life. It is also keeping us in a place of suffering, whether we realize it or not.

Take the models of success that society gives as an example: people with bulging muscles or bulging wallets, fame or power, beauty or balls. When you look a little deeper, they are often accompanied by misery, superficiality, or self-destruction. If you don’t relate to yourself in a way that is sovereign, as my own experience showed me, those acts of power will also be acts of defeat, because they regularly involve a fundamental betrayal of yourself, and that causes a profound energy leak.

Sovereignty

Sovereignty doesn’t have an underbelly. It is about a deeply life-affirming, respectful, energizing, and enlivening relationship with yourself and other people in such a way that fully preserves you and allows you to live in the fullest expression of yourself.

The path to regaining sovereignty begins with becoming aware of the shackles binding us and then learning to break free from them. Sovereignty offers a way to stay centered and grounded despite the chaos, the unpredictable nature of these times, and the constant noise. If ever there was a time when we desperately needed inner strength, poise, and the ability to maintain equilibrium and power no matter what—it’s now.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a period marked by tragedy. Yet, amidst the subsequent chaos, war, and division, a profound realization emerged: facing the reality of death prompted a widespread awakening to the value of life, and an understanding of the importance of living life on our own terms.

When you are sovereign, you not only experience happiness and well-being but also maximize your gifts and strengths, bringing out the best in yourself. Just like your thumbprints are unique, your whole being is a unique expression of life and the individual gifts you bring to the planet—whether you realize it or not. Sovereignty allows you to express, completely. In that way, sovereignty is not just a gift to you, it is a gift for everyone you come in contact with.

And sovereignty is contagious. A U.S. Marine Corps veteran who was in one of my research studies shared with me that, during grueling challenges, it wasn’t the youngest and most able-bodied Marines who succeeded; it was often the smallest, oldest, or even weakest. What they had that made them different was inner sovereignty. And they became the leaders—seeing them succeed helped everyone else stand taller. Reminding someone of their sovereignty makes their flame grow stronger and brighter. If you don’t want to gain sovereignty for yourself, then do it for everybody else.

As you become aware of your sovereignty, three areas of your life, in particular, will strengthen to a whole new level:

Your awareness and discernment in your everyday experiences, choices, and interactions

Your energy as you start to live in a more life-supportive rather than depleting way

Your courage, strength, and boldness

This may be challenging at times because it will awaken you to the extent of the subjugation, limiting beliefs, and inertia you have unknowingly placed yourself in. But it will also open your perspective to the possibility of living life at your fullest: with your eyes wide open, spirit soaring. As you free yourself, you will notice a shift in your life force, and this power, in turn, will help you free others.

I want to invite you to a playground of freedom and authenticity, vision and innovation, personal potential and fulfillment. I want you to hone these qualities and bring them to your consciousness in a joyful, practical way that will also hopefully make you laugh out loud from time to time. I invite you to the beautiful landscape of possibilities that are wide open to you, and within you, when you start living in your sovereignty.

A Key Sovereignty Practice:

Meditation: The quality of our life depends on the state of our mind. On a day where your mind is disturbed, any little thing can trigger anger, frustration, or sadness. On a day when your mind is calm and centered, it won’t. Meditation makes you sovereign. It also makes you sovereign because your awareness grows stronger. And you cannot be sovereign without awareness.

Breathwork: For many of us anxiety and stress are high. It is difficult to sit in meditation when your mind is buzzing. It can even be frustrating. Our research at Stanford and Yale on breathing exercises for veterans with trauma, and students with high stress, shows that certain breathing exercises can be extremely helpful. The longer protocol we researched is called SKY Breath Meditation (which you can learn through a nonprofit called Art of Living or, if you are veteran/military, through a nonprofit called Project Welcome Home Troops). It conditions your nervous system for calm much like you condition your muscles at the gym for strength.

Here is a simple breathing exercise you can try at home that can help you calm down in the moment.

To get an idea of how breathing can calm you down, try changing the ratio of your inhale to exhale. When you inhale, your heart rate speeds up. When you exhale, it slows down. Breathing in for a count of four and out for a count of eight for just a few minutes can start to calm your nervous system. Remember: when you feel agitated, lengthen your exhales.

While a short breathing exercise like this can be effective in the moment, a comprehensive daily breathing protocol such as the SKY Breath Meditation technique will train your nervous system for resilience over the long run.

You Did Not Come Here

You did not come here To play small, To hide yourself, To blend into the wall. You did not come here To dim your light, To crouch in fright, To lie in a ball.

You came here To light a fire Within your own heart, That it might Warm and light the fire Within others’ hearts, That it may set ablaze old rotting beliefs, That it may light the way to greater truths, That it may burn to ashes systems of old Grown toxic with mold, That you may make room For new plants to bloom.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

As a best-selling author, Yale lecturer, and international keynote

speaker, Seppälä teaches executives at the Yale School of Management

and is faculty director of the Yale School of Management’s Women’s

Leadership Program. A psychologist and research scientist by training,

her expertise is the science of happiness, emotional intelligence,

and social connection. Her best-selling book The Happiness Track

(HarperOne, 2016) has been translated into dozens of languages. Her

new book is Sovereign (Hay House, 2024). Seppälä is also the Science

Director of Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education.

As a best-selling author, Yale lecturer, and international keynote

speaker, Seppälä teaches executives at the Yale School of Management

and is faculty director of the Yale School of Management’s Women’s

Leadership Program. A psychologist and research scientist by training,

her expertise is the science of happiness, emotional intelligence,

and social connection. Her best-selling book The Happiness Track

(HarperOne, 2016) has been translated into dozens of languages. Her

new book is Sovereign (Hay House, 2024). Seppälä is also the Science

Director of Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education.

You Don’t Have to Change to Change Everything

© Beth Kurland, PhD

Adapted from You Don’t Have to Change to Change Everything: Six Ways to Shift Your Vantage Point, Stop Striving for Happy, and Find True Well-Being, by Beth Kurland, Ph.D. Reprinted with permission from Health Communications, Inc.

From “hole self” to “Whole Self”: Finding Our Deep “Well” of Well-Being”

In my experience sitting with hundreds of patients over the years, and from my own many years of therapy, I have come to see that we have what I call a “hole” self and a “Whole” Self. The hole self is our small self; it is made up of the many parts of us that we identify with as who we are, especially in times of challenge. This hole self often feels “not enough” and has a chronic sense of “something wrong, something missing.” The hole self is caught in a narrow, limited view and cannot see a bigger picture. It is our default, the place we revert back to when things get difficult, and when younger parts of us that hold painful memories are triggered by current situations that remind us (often unconsciously) of earlier experiences.

Small self operates from our survival brain, in the service of trying to protect us, often in ways that don’t give us access to our fullest resources. This sense of not enough and something wrong may have had some evolutionary value for our Stone Age ancestors, who needed to be on high alert and for whom messing up could cost them their lives…

However, we all have a Whole Self that is here, that is always with us. When Whole Self is online and present, there is more expansiveness, a sense of more space, and an ability to see a bigger picture. From Whole Self we can take a mindful view of things instead of being lost in a myopic view. Whole Self is a more embodied self, connected with mind, body, and heart—and connected with an inner wisdom, an inner knowing, about what is best for our well-being. Whole Self operates from our caring circuits (our social engagement system), with our more newly evolved “operating system” online so that we can access our fullest potential and all the possibilities available to us. When we are stuck in hole self, there is suffering; when we shift to Whole Self, there is greater ease and wellbeing.”

“Hole self” – How we end up in the hole

In my thirty years of clinical experience, and in my own personal journey, I see that so many of us struggle with a deep sense of “not good enough.” I know I struggled with this for many years of my life —about my body, about having a sense of needing to do more, be more, achieve more, or be perfect — in order to feel loved, accepted and most importantly, “okay” within. Due to the negativity bias of the brain, (or the “Velcro problem” as I affectionately like to call this after Rick Hanson’s teaching that the brain is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones), we start off from the get-go with a propensity to see our own faults and overlook our strengths. How easy it is to focus on that one mistake we made and completely overlook a week or a lifetime’s worth of things we’ve done well. This sense of not enough is also reinforced by our cultural conditioning (at least in the culture I grew up in, in the U.S., where I was bombarded with messages from the media, advertising and the like that “I should be happy all the time like those people in the pictures.”) Enter social media, which certainly feeds into this for many people, leaving them feeling that they are falling short in some way if their life doesn’t look like the pictures that everyone else is posting.

In addition to certain societal messages that emphasize hedonic happiness and can leave us often feeling like we are falling short, our own early childhood conditioning frequently furthers this messaging. Even well-meaning parents often give children messages implicitly or explicitly to put away their sadness, “cut it out and stop whining,” or “stop being angry and let’s see that smile.” The message learned is that these more unpleasant emotions aren’t okay to feel.

Additionally, our biological wiring towards seeking what’s pleasant and avoiding what’s unpleasant/ painful doesn’t help matters either. While this was helpful for our Stone Age ancestors’ survival to avoid external, physical threats, it doesn’t work so well with our inner psychological pains. When stuck in the protective circuits of our sympathetic and dorsal vagal branches of our nervous system, trying to keep us “safe” through adaptive fight, flight or freeze, we often don’t have access to other inner resources that can better help us face our modern-day challenges. In our tendency to push away and avoid our difficult emotions, without knowing how to meet our own suffering, we end up disconnecting from ourselves along the way. And so, the hole deepens.

The consequence of this is that when difficult emotions show themselves, as they inevitably will (the First Noble Truth in Buddhism – there is suffering), we often think there is something wrong or missing. I am struck by how many clients I have sat with through the years in the midst of deep grief or loss who say to me “I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” “I’m falling apart,” “I should be stronger,” “I’m sorry I’m crying.” From a letter I found to my then boyfriend at the age of 15 after my mom died, I wrote how I didn’t know what was wrong with me, I should be happier and I’m not. This struggling against our own emotions deepens the hole. Sometimes we can feel stuck there for long periods of time.

Making the shift from hole self to Whole Self

What I have found through my own personal healing journey, my practice with mindfulness and mind-body modalities, and through my work with my clients, is that we don’t have to try to fix or change ourselves or our feelings (which often just reinforces the “hole” self). Instead, we can meet ourselves right where we are but learn to shift our vantage point, the place from which we are looking. When we do this, we change the very nature of our relationship to our difficult emotions, and possibilities open up that we hadn’t seen before.

This shift from hole self to Whole Self begins when we can shift from the protection circuits of our sympathetic (or dorsal vagal) nervous system (that are adaptive and reflexive but, when stuck there, may not be serving us optimally in our moments of difficulty) and access our social engagement system, with its more newly evolved ventral vagal pathways. From here, we have access to far more inner resources to help us meet our psychological challenges.

(It makes sense that when we are running from a tiger, we have tunnel vision and react reflexively; yet when we are not trying to fight, flee or play dead in the face of a tiger, we have access to care, connection, perspective and seeing a bigger picture, compassion and self-compassion, creativity, confidence, etc.).

In my clinical work and personal journey, I have found six shifts of vantage point to be immensely helpful in moving from hole self to Whole Self:

The Anchor View

Whole Self emerges first and foremost from a regulated nervous system, grounded in enough cues of safety that whatever “threats” might be there don’t keep us stuck in a full-on fight-or-flight response. Imagine being in the midst of a storm at sea. Surely without an anchor, we are at the whim of the storm. But if we can grab an anchor and look out from the vantage point of the anchor, we can watch the storm and let it pass without it taking us with it. And if we follow the anchor far enough down below the surface, there is stillness, calm. As Deb Dana teaches, the world looks much different from a nervous system regulated with ventral vagal energy. From here we can access qualities such as care, compassion, appreciation, joy, love, courage, creativity, etc.

How? There are many ways we can access the anchor view. Some of my favorites include using guided imagery, breathing exercises (particularly slowing down the exhalation), mindful movement and calling up feelings of being cared for. As I have seen first-hand using biofeedback in my office, even just a few minutes of interrupting our reflexive survival circuits can help to bring more regulatory and balanced energy into the nervous system.

One client with whom I’ve been working was struggling with losing her patience with her toddler and then beating herself up for this, feeding an unhelpful cycle of self-denigrations. We discovered that her toddler’s emotional dysregulation triggered her own memories as a child of being in a chaotic environment and were being read as cues of “threat” for her nervous system. We worked with a short practice that she did each day before getting out of bed, and again before coming in the door from work, where she used breathing and imagery of a tree with deep roots to help her nervous system feel safe and grounded. From here, she used mental rehearsal to play out typical scenarios of how her toddler might behave, helping her nervous system stay grounded and re-learn that she was actually safe in these moments. She found that in learning over time to take the anchor view, she had access to very different inner resources that helped her remain present, more patient, and in connection with her toddler.

The Child View

Once our nervous system is in a state of regulation, we can begin to turn toward our inner experiences with curiosity and friendliness. This is not what we typically do when we come up against difficult emotions, but it is a move we can cultivate. This is an important quality of mindful awareness. Like a small child who has not yet learned otherwise to label and judge, who is fascinated by the crinkly paper or approaches the cardboard box or spoon and pot with great interest, we can learn to adopt some of these child-like qualities to bring toward our inner experiences.

How? One of the practices I like to use is to “Stop, Drop and Get Curious.” It involves having the initial awareness to stop when we notice an inner disturbance, to drop into the body bringing full awareness there, and to get very curious about what it feels like in there. The other day I was feeling harried, trying to get a lot done, rushing around doing errands, and eager to get home to complete a project. I got stuck behind a very slow driver (you know the one) who was crawling at a snail’s pace for miles. I immediately became irritable, frustrated and tense. I remembered (as I sometimes do) to stop, drop and get curious. After a few calming breaths to interrupt my habitual reactivity, I noticed constriction in my chest and tightness gripping around the steering wheel. I noticed shallow, restricted breathing, intense, uncomfortable energy in my body and not so kind thoughts in my mind. “Oh, this is what frustration feels like. How interesting, my body is preparing to fight or flee, but there’s no tiger chasing me here.” From this place of curiosity, my Whole self could come online and help me loosen my grip (literally and metaphorically), recognize my response was not helping me feel “safer,” and guide me toward deeper breaths, a more helpful perspective, and a state of wellbeing.

The Audience View

Like the third step in a dance, the audience view helps us to take a mindful step back from whatever is going on. Rather than being the actor on stage, being swallowed up in the drama of the moment, when we can relocate ourselves in the audience there is more space between us and our difficult emotions and reactions. This is the gift of mindful awareness. Importantly, it is not a dispassionate view. I like to think of it as having the quality of sitting in the audience watching a child or niece or nephew on stage. You would likely feel care and warmth toward them, yet recognize you are not them, not identified or fused with their emotions on stage. When we can take this kind of audience view with our own inner experiences, it shifts our relationship to these experiences and creates that critical mindful pause in which change and choice can emerge.

How? One simple exercise that I have found to be very powerful with clients and audiences alike is to work with the phrase “I notice that…” Instead of using our typical language (at least in the English language) to characterize our inner experiences — “I’m so angry; I’m so anxious; I’m so stupid” — we add the phrase “I notice that…” beforehand. When I say “I’m so angry” I feel very identified with the part of me feeling anger. When I say “I’m so stupid” it feels like this is absolute truth and there’s nowhere to go from there. When I can shift to saying, “I notice that I’m feeling a lot of anger in my body right now” or “I notice that I’m having the thought that I’m so stupid,” it immediately shifts me into the audience view. I am no longer caught in small self on stage, but I am Whole Self who sees from the audience that I am struggling. I sense more space between me and my emotions, and it feels as if I have taken a half step back. A further way we can work with this is to look through the lens of the autonomic nervous system and name what we see: “I notice that my nervous system is going into a state of protection, of fight (angry) energy”; “I notice that my nervous system is trying to protect me after the mistake I made by reacting to my embarrassment and going into shut down mode.”

The Compassionate Parent View

Once we learn to regulate our nervous system, turn with some curiosity and friendliness toward our inner experiences, and get some helpful distance between us and the physical, mental and emotional activity or our body-mind, we are ready for the next shift in vantage point: the compassionate parent view. Imagine a small child in distress and a parent having three different reactions to that child in distress: 1 – ignoring the child completely; 2 – yelling at the child to cut it out and stop fussing; 3 – putting an arm around the child, acknowledging their upset, seeing their pain, and offering a comforting presence without needing to fix it or talk the child out of their feelings. We often meet our own suffering with the first and second reactions. Few of us have learned to meet and greet our distress as the compassionate parent in the third example.

The ability to do this is fundamental to many self-compassion practices and programs and touches upon the power of Internal Family Systems work. In my experience, learning how to meet our inner distress as the compassionate parent (or friend/mentor or whatever image is helpful) from the Whole Self that can be present with our pain (while not being swallowed up in it or ignoring it) can be transformational in our healing journeys.

How? I had a client I’ve been working with for some time, who was familiar with working with the above three vantage points. She experienced the breakup of a relationship and was consumed by this, preoccupied and stuck in ruminations about how she was unlovable and defective. Lacking compassionate parents in her own childhood it was especially hard for her to internalize a sense of compassion toward herself. But she was a devoted and loving aunt to several teenage nieces, and often supported them in the midst of their heartbreaks and struggles. Using this experience of compassion that was already familiar to her, we helped her call this up and embody this felt sense of compassion toward another. As the compassionate aunt, she could see that her own nieces’ heartbreaks and losses were not caused by their deficiencies, but by the human condition of which loss is a part. From here, as the embodied Aunt, she could begin to turn toward her own sadness and loss, inviting it into the room, imagining it sitting across from her and being present to it, not from the “self” consumed in loss and self-loathing, but from the Self spacious enough to hold the suffering of another.

The Mirror View

While hole self sees our flaws and imperfections and feels there is something wrong with us, Whole Self sees our flaws and imperfections as well as our strengths and is able to live a meaningful life drawing upon these strengths and choosing actions aligned with our deepest values. During my internship after graduate school, I had the privilege of working with Dr. Robert Brooks, a skilled clinician and expert on resilience. He taught me that instead of focusing on psychopathology and what’s wrong, we can focus on identifying people’s “islands of competence” and working from strength. I think of this as holding a mirror up for my clients and helping them see what is already working, helping them see the courageous, resilient parts of them, and helping them identify the inner resources that are already here. Rick Hanson’s teachings in positive neuroplasticity have also been immensely helpful for me. I have found that change comes about most profoundly not by finding what’s wrong and fixing it, but by finding what’s right and strengthening it. From this mirror view, when we can work from strength, we are much more able to take actions and make choices that align with our values and what’s important to us. Also, when we can accept our imperfections and see our strengths, we send greater cues of safety to our nervous system to help us move toward what matters (as opposed to self-criticism which tends to get in the way of moving forward).

How? Try this over the course of the following week. Take a few minutes each day to make note of and write down anything you do that moves you in the direction of well-being. Look for small things that you might otherwise overlook or discount, for example: turned off the TV and went to bed early; savored a cup of tea before work; stopped to say hi to my neighbor and check in on her; called a friend on the way to work and enjoyed the connection; went for a walk at lunch to get some movement; caught myself in a moment of irritation and took a moment to calm. Make note of any positive outcomes of doing this (had more energy the next day, started my day with more ease, felt a sense of connection, felt an ability to care for myself, etc.). When you can look in the mirror and see what moves you in the direction of well-being (no matter how small), how does that effect your mood, motivation, and momentum to take further actions in the direction of well-being? What inner qualities (e.g. patience, perseverance, acceptance, compassion, care, awareness, perspective) are you calling upon to take the small steps you did, and how might you dial into and call up those inner qualities when you run into day-to-day challenges?

The Ocean View

As much as the previous five vantage points help us work toward a sense of inner wholeness and connection with our Self, there is also a wholeness we experience when we connect with and feel a oneness and interconnection with the greater world outside of us. There are many ways one might experience this interconnection: being part of a larger family unit, part of a community of some kind, sensing a connection with the natural world, the global world, the spiritual world, or the universal consciousness.

When we are caught in the challenges of life it is easy to feel as if we are alone, isolated, disconnected. This sense of separateness is magnified by the nature of our mind and the duality in which we experience ourselves in the world. When we open even beyond our Whole Self to include a sense of the Whole that is all around us and of which we are a part, a further shift in consciousness is available. From here we can experience expansiveness, interconnectedness, deep peace, equanimity, and awe. When we can expand our “audience view” from above and ask “who or what is aware of the one sitting in the audience?” we begin to tap into the nature of non-dual awareness. From here we can ask “How am I aware of the one who is sitting in the audience? Where does this knowing come from?” These inquiries allow us to get a glimpse of awareness of awareness itself, leading to profound shifts in what it means to be a Self in this interconnected world. We begin to experience a sense of no longer being the isolated wave, but instead recognizing the possibility that we are, in fact, the ocean itself that holds our wave-like experience within something far more expansive. We can glimpse the world through the ocean view.

How? For the first part of my life, I lived life with a roadmap approach. I focused on getting from point A to point B in a straight line, a linear and separate path. As I have gotten older, I am realizing that this road-map approach to life doesn’t quite fit me anymore. I think of life now a bit more like a labyrinth, a winding circular path always leading back to the center, with a kind of oneness and connection with the center wherever you are on the path.

You might take some time to draw a labyrinth (or if you are interested, see if you might find one that you can visit and walk). What for you represents the center of your labyrinth? What is it that you would like to remind yourself of, whenever you feel lost, that you might “come home” to? (This could be a deep sense of stillness and calm at the core of your being; a sense of connection with nature or spiritual transcendence; a sense of belonging to your community; a deep connection with your loved ones; a connection with God, spirit or the aliveness around you). Use words, pictures, symbols, or images to represent your center of this labyrinth. Whenever you feel that you are metaphorically losing your way, picture walking your labyrinth knowing that no matter which direction you walk you will find your way to center.

When we shift our vantage point, we shift from hole self to Whole Self. From this place of wholeness, from a nervous system grounded and regulated in safety, from an ability to be a mindful witness and a compassionate presence toward the hurting parts of us, from a place of being able to accept our imperfections and humanness and see our strengths, and from a sense of Self interconnected with a greater Whole around us, we have access to a treasure trove of inner resources to help us cultivate well-being. From here, all manner of possibilities arise. This is where true change lives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Beth Kurland, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, Tedx and public

speaker, mind-body coach, and author of four books. Her newest

book is You Don’t Have to Change to Change Everything: Six Ways

to Shift Your Vantage Point, Stop Striving for Happy, and Find True

Well-Being. She is also the author of three award-winning books:

Dancing on the Tightrope: Transcending the Habits of Your Mind

and Awakening to Your Fullest Life; The Transformative Power of Ten

Minutes. An Eight-Week Guide to Reducing Stress and Cultivating

Well-Being; and Gifts of the Rain Puddle: Poems, Meditations and Reflections for the Mindful Soul.

Beth Kurland, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, Tedx and public

speaker, mind-body coach, and author of four books. Her newest

book is You Don’t Have to Change to Change Everything: Six Ways

to Shift Your Vantage Point, Stop Striving for Happy, and Find True

Well-Being. She is also the author of three award-winning books:

Dancing on the Tightrope: Transcending the Habits of Your Mind

and Awakening to Your Fullest Life; The Transformative Power of Ten

Minutes. An Eight-Week Guide to Reducing Stress and Cultivating

Well-Being; and Gifts of the Rain Puddle: Poems, Meditations and Reflections for the Mindful Soul.

With a passion for and expertise in mindfulness and mind-body strategies, she brings over three decades of experience to help people cultivate whole-person health and wellness. Drawing on research and practices from mindfulness, neuroscience, positive psychology, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and polyvagal theory, she teaches people practical tools to grow the inner resources for resilience and well-being. On her website, BethKurland.com, you can find audio courses, meditations, and free resources.

Healing With Science and Shamanism

© 2024 Peter A. Levine, PhD

An Autobiography of Trauma by Peter A. Levine, Ph.D. © 2024 Park Street Press and Sacred Planet Books. Printed with permission from the publisher Inner Traditions International. www.InnerTraditions.com

People have sometimes described my healing work as being almost mystical or shamanic. While I certainly have been influenced by crosscultural studies about shamanic healing practices and I have had opportunities to meet with various shamans and indigenous healers throughout the world, it has nevertheless been my lifetime task to prove that such labels are too elusive and woefully insufficient. In other words, my aim has been to demonstrate that the approach I have developed can be taught and practiced in Western secular society. The biological tradition that led me to this work has its origins in the highly “objective” sciences. Only later did my access to embodied spirituality organically emerge from a rock-solid foundation of biophysics, neurobiology, and ethology,* combined with complexity theory and systems theory.

*Ethology is the study of wild animals in their natural environments.

Around 1972 I began teaching my healing approach to a dozen bright Berkeley therapists, during biweekly meetings held at my Wildcat Canyon “tree house” at 6182 McBryde Ave. Today, fifty years later, I may finally have completed my task of proving that this form of healing is not simply derivative of my individual gifts. Rather, the evolving healing method, currently called Somatic Experiencing (SE), named for the experience of the sensing, living body, is indeed scientifically based, teachable, and transmissible. One of the challenges in teaching SE, as well as researching its effectiveness, is that the method is not exclusively formulaic or a codified protocol, but rather an unfolding organic process that involves basic principles and building blocks. Despite this hurdle, however, a number of scientific studies have demonstrated that its mode of operation leads to strong, solid clinical efficacy.

In any case, from its inception with the “dirty dozen” in my humble tree house, the work has spread worldwide. By 2022 its reach had extended to forty-four countries through the diligent work of more than seventy international instructors. Together they have trained over 60,000 practitioners. As I reflect on this explosive growth and upon the trajectory of my life, I find myself truly dumbfounded. I have, without realizing it, become something akin to an unsuspecting and unlikely “prophet.”

To the question of whether I have done enough, I can answer with a gentle “yes.” Indeed, the responsibility of bringing this work to a troubled world now rests on the shared shoulders of the dedicated international SE faculty.

And what about the more elusive question, “Am I enough?” Of this conundrum, I must unburden myself, for I am simply a work in progress. Writing this book, for me, has been a way to collect my thoughts, memories, dreams, and reflections. The “am I enough” query relates deeply to my struggles with opening myself to love and accepting the feeling of being loved. I have often searched for the love of the “magical other” in an effort to find the one who would release me from my wounds. Along that road, I have been gifted with a number of precious woman lovers, as well as deep and persistent friendships from both genders.

But back to 1972. At our small Berkeley haven of kindred spirits, it was my job and our shared task to explain the how, what, and why of my support and facilitation for individuals who wished to heal their overwhelming stress and traumas. We were also trying to uncover a means by which our healing techniques could be methodically and holistically taught to others. At that time I was working on my interdisciplinary doctorate in the medical and biophysics departments at UC Berkeley. Hence, I was steeped in the fascinating world of the hard sciences including quantum physics, mathematics, and biology. I had a special interest in the nervous system and brain function. These explorations helped me understand the autonomic or involuntary nervous system, the upper brain stem, the cerebellum, and the limbic system. These are anatomical features we share with other mammals, and which give rise to, underlie, and shade all our sensations, emotions, and perceptions. These basic systems also shape many of our core beliefs.

Bottom-Up

As I evolved my body/mind approach, rather than utilizing a hierarchical, top-down system typical of traditional academic “talk” and cognitive behavioral therapies, I explored a “lower-archical” or bottom-up understanding. This process involved beginning the therapeutic work by engaging with bodily sensations as well as inner motor impulses and drives. In the words of the Kybalion, the Hermetic philosophy of ancient Egypt and Greece, “As below, so above.” My approach aspired to unite the two routes, bottom-up and top-down, body and mind, into a holistic process that respected the totality and innate wisdom of the living human organism. In other words, I formulated a method that could guide those seeking healing to pay attention to their own somatic bodily experiences, along with the emotions and meanings we attach to our interoceptive bodily “landscapes.”

We Are All Animals

For me, the icing on the cake, that delicacy of scientific inquiry, was my fascination and appreciation of ethology, the study of wild animals in their natural environments. Ethologists’ respect for nature gave me an unexpected and juicy clue as to how individuals are traumatized and, more importantly, how we can heal. I began to use the ethological methodology of naturalistic observation with my clients. Like the ethologists, I would take note of people’s subtle gestures, involuntary postures, facial expressions, heart rates, respiratory (breathing) rhythms, and skin color changes. All these are indicators of autonomic activity and precursors to feelings and eruptions of emotion. After all, we humans are mammals, albeit special ones, but mammals just the same! And as my childhood hero Yogi Berra, the famous 1950s catcher for the New York Yankees, put it: “You can observe a lot just by watching.” And that is exactly what I did—month after month, year after year, decade after decade. I continued to emulate the great ethologists I had come to admire so deeply, particularly the research of Nikolaas Tinbergen, who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology.* From 1974 to 1977 I corresponded with Tinbergen, then a professor at Oxford University, by “snail mail” and by phone via the new transcontinental underwater cables. This precious communication cost me much of my monthly graduate student stipend, as this was long before the expediency of cell phones and the internet. I was struggling with the doubt that I might just be imagining my observations and their significance for health, stress, and dis-ease. Tinbergen’s acknowledgment and support buoyed me as I continued my pursuits.**

*See “Nikolaas Tinbergen Facts” on The Nobel Prize website.

**During this time, I also received some additional encouragement from Raymond Dart, the anthropologist who first

discovered Australopithecus on the African savanna—the transitional “ape-man.”

At the same time, I had a major setback in my academic progress. The chairman of my thesis committee, leading cell biologist Professor Richard Strohman, said I would only receive my doctorate over his dead body. He bluntly informed me that my work bridged too many disciplines to be valid and truly scientific. This was during the period, mind you, when I was in an interdisciplinary program at UC Berkeley called Medical and Biological Physics. It was a graduate school arrangement that allowed a few of us to study different, though potentially related fields. For me it involved a synthesis of biology, physiology, ethology, brain research, a branch of mathematics called catastrophe theory, and systems theory. Strohman’s categorical rejection of my dissertation left me utterly despondent and not knowing where to turn.

I Give Thanks for Help Unknown, Already on Its Way

Thankfully, my dear friend Dr. Ed Jackson, who during that time was an adjunct faculty member at the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley, was also allowed to serve on the committee. Ed came to my defense and suggested we send my dissertation to leading researchers in each of the above fields. After a couple of months passed, with no response, I gave up in resignation and began to apply for a new doctoral program in psychology. But then on a sunny November day, a friend told me how she had been a guest at Professor Strohman’s house for one of his infamous parties. Speaking from the sixties: the professor had a penchant for tall blonds, fine wines, and vintage Porsche convertibles. In any case, at the party my friend overheard a conversation between Professor Strohman and a young graduate student who was interested in studying stress. The student wondered if there were any seminars in that particular field. To that question, Strohman replied that she should speak with his “protégé” Peter Levine. Yes, those were his actual words! This juicy gossip meant I could celebrate that I was finally in the clear and could breathe again. I could at last move forward in my academic and scientific career.

When I next met with Strohman, he sheepishly congratulated me, as he had received several accolades from field leaders about “his” graduate student. One commenting scientist was Hans Selye, the innovative developer of the physiological concept of stress, who made significant contributions to science’s understanding of the body’s short- and long-term responses to stress and “strain.” As a young medical student, Selye had also been marginalized by his clinical professors when he observed there were more similarities than differences across a diverse set of diseases with which his professors’ patients had been diagnosed. In an emperor-has-no-clothes moment, Selye observed they all simply looked sick. Essentially he reasoned they all looked that way due to the “wear and tear” of stress. In other words, he proposed that the effect of stress was like a bank ledger: you can continue to withdraw money until you are in the red. His hypothesis was that, just like a savings account, there is only so much you can withdraw. When the reserves run out, your body becomes bankrupt. You then become sick, just like the many patients he had observed in medical school.

In my 1976 doctoral dissertation, however, I argued against this passive bank-ledger view of stress. I began instead to develop the concept of core resilience as a dynamic antidote for accumulating stress. In my thesis I argued strongly against Selye’s concept of the human body as a financial account or bank ledger with only finite resources. I demonstrated, rather, that whenever we face threat or danger, our autonomic nervous system activates, or “charges.” However given the right conditions, the nervous system rebounds and “discharges” this eroding activation. This dynamism restores equilibrium, internal regulation, and balance, and thus promotes overall resilience.

I also had a unique window into stress resilience when I lived a lifelong dream of working for NASA. Around 1978 I had the rare opportunity to work as a stress consultant to NASA, in a joint consortium with UC Berkeley on the early development of the space shuttle program. It was my assigned task to monitor the physiological squiggles, including heartbeat and respiration, that were sent back to Earth as the astronauts lifted off and then entered the microgravity of Earth orbit. At this point, a few of the astronauts would become nauseous and might even vomit. This “zero G sickness” was more than just annoying, it could damage the electronics and cause a potentially catastrophic malfunction. My assigned task was to monitor these physiological signals so as to predict when the vomiting might occur and then, of course, develop strategies to help stop it. Thus while I was seeing many of my clients become overwhelmed by stress, I saw the opposite response with most of the astronauts.

The riveting question that emerged for me was: Is it possible to help “train” the autonomic response of my clients to develop core resilience, so they too can rebound like the astronauts did?

When Selye read my doctoral dissertation, he had the grace and humility to correspond with me. He did this even though I had argued against much of his basic theory, at least with regard to the capacity for resilience as an antidote to what he had called the “wear and tear” of stress. In a letter to Professor Strohman, he magnanimously wrote that my concept of resolved versus accumulated stress was a major contribution to a comprehensive understanding of stress. I would hope, likewise, to have some small degree of humility when someone, perhaps a student or colleague, challenges any of my theories or practices.

With gladness and appreciation, Selye and Tinbergen provided me with a foothold into a theoretical basis for my clinical observations. This gave me the confidence to immerse myself in this inquiry for many decades. With their generous support and encouragement, I would thus continue to explore my investigations, vision, and theoretical conclusions, despite my many apprehensions and insecurities. For that reason, I am sincerely thankful to both Professor Tinbergen and Dr. Selye, who together provided me with a contribution beyond measure.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peter A. Levine, PhD, is the renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing.

He holds a doctorate in medical and biological physics from the University

of California at Berkeley and a doctorate in psychology from International

University. The recipient of four lifetime achievement awards, he is the

author of several books, including Waking the Tiger, which has now been

printed in 33 countries and has sold over a million copies. https://www.

somaticexperiencing.com/home.

Peter A. Levine, PhD, is the renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing.

He holds a doctorate in medical and biological physics from the University

of California at Berkeley and a doctorate in psychology from International

University. The recipient of four lifetime achievement awards, he is the

author of several books, including Waking the Tiger, which has now been

printed in 33 countries and has sold over a million copies. https://www.

somaticexperiencing.com/home.

Skillful Means: Self-Hypnosis

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

Self-Hypnosis

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Self-hypnosis is an important branch of modern hypnotherapy, used either in addition to guided hypnosis. It can be done using a CD or tape recording that leads you into a trance state, or through a learned routine, such as the one below. Self-hypnosis can be an effective therapy for pain relief, gastrointestinal upset (especially in the case of irritable bowel syndrome), a tool to assist in weight loss and addiction recovery, and to relax, relieve stress and anxiety, and to promote general well-being. By leading the conscious mind into a relaxed, unfocused awareness, it becomes susceptible to positive autosuggestion.

METHOD

Summary

Sink into a state of complete relaxation and trance, state the necessary affirmations, and reemerge.

Long Version

Find a quiet place where you can turn ringers off of phones and otherwise ensure silence for at least half an hour. Sit or lie down comfortably; many people enjoy using a recliner for self-hypnosis sessions. Ease into a restful position, with arms and legs lying heavily and loosely. Don’t cross your legs as they may start to fall asleep and leave you uncomfortable.

Close your eyes and begin to breathe deeply in through the nose and out through the mouth. Slowly relax your body by visualizing the tension and stress flowing out of your muscles, starting at your toes and moving up your legs, through your torso and arms, and finally your head. Let your heavy limbs become lighter with this visualization.

In a similar way, let the mental sensations of fear, stress, and anxiety flow out of your mind. If they arise, instead of trying to force them out, just observe them and let them slowly pass away. Visualize with each breath these negative feelings leaving with each exhalation and a bright white light coming in with each inhalation, bringing with it positive feeling and a healing energy.

Now, visualize that you are at the top of a flight on ten stairs. Visualize yourself descending this staircase slowly, counting down to yourself with each one, from ten to one. When you reach one, you will be at a doorway. Visualize opening this door to a calm paradise, full of beauty and serenity. Allow yourself to relax and enjoy the natural beauty of your personal haven, breathing in its purifying air deeply. While you are here, you may decide to make some affirmations. Visualize yourself walking through your serene place until you come to a body of water. Look down into this body of water and see your reflection looking back at you. With relaxed and loving resolve, repeat between one and three affirmations silently to yourself two or three times each. For more on affirmations, read the article here.

When you have made your affirmations and explored your paradise as fully as you wish, return to the doorway. Visualize yourself opening the door and ascending the staircase slowly and relaxedly, counting up silently from one to ten. When you have reached the top, take three easy breaths and let them bring you back to the outside world. Rest silently with your eyes closed for a little longer, then allow them to open and take in the world from your newly relaxed and refreshed state.

HISTORY

The 18th-century German physician Franz Mesmer developed a primitive form of hypnosis based on what he called “animal magnetism”; later, the Portuguese monk Abbé Faria postulated that hypnosis-type effects were due to the power of suggestion instead. In 1841 the Scottish physician James Braid took these ideas and developed both traditional guided hypnotism and selfhypnotism. Later, psychologists like Émile Coué refined autosuggestion techniques. In the 20th century, research confirmed that self-hypnosis had similar effects to “hetero-hypnosis” and proved its worth as a self-help technique.

NOTES

-

If you find hypnotic and autosuggestive techniques helpful, there are a great many different possibilities. Follow the links below under “See Also” for some suggestions. You may want to use self-hypnosis as a supplement to hypnosis sessions guided by a therapist. This is a very effective way to maximize therapeutic benefit while saving time and money.

SEE ALSO

EXTERNAL LINKS

Hypnosis Downloads: Over 500 MP3s for self-hypnosis

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise

The Wellspring Institute

For Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom

The Institute is a 501c3 non-profit corporation, and it publishes the Wise Brain Bulletin. The Wellspring Institute gathers, organizes, and freely offers information and methods – supported by brain science and the contemplative disciplines – for greater happiness, love, effectiveness, and wisdom. For more information about the Institute, please go to https://www.wisebrain.org/wellspring-institute.

If you enjoy receiving the Wise Brain Bulletin, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Wellspring Institute. Simply visit WiseBrain.org and click on the Donate button. We thank you.