News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 17.1 • February 2023

In This Issue

Stay Right When You’re Wronged

© 2023 Rick hanson, PhD

Excerpted from Making Great Relationships: Simple Practices for Solving Conflicts, Building Cooperation, and Fostering Love (January 2023). Reprinted with permission from Penguin Random House.

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at https://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin. Michelle Keane edits the Bulletin, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online. To subscribe, go to https://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.It’s easy to treat people well when they treat you well. The real test is when they treat you badly. It’s natural to want to strike back. It might feel good—for a little while. But then the other person might overreact, too, and now you’re in a vicious cycle. Other people could get involved and muddy the water. We don’t look very good when we act out of upset, and others remember. It gets harder to work through issues in reasonable ways. When you calm down, you might feel bad inside. So let’s explore how you can stand up for yourself without the fiery excesses that have bad consequences for you and others. How You can use these suggestions both in the heat of the moment and as a general approach in a challenging relationship.

Get Centered

This step could take just a few breaths, or if you like, a few minutes. Here’s a quick review of psychological first aid:

- Pause—You rarely get in trouble for what you don’t say or do. When I work with couples, much of what I’m trying to do is to s-l-o-w them down to prevent runaway chain reactions.

- Have compassion for yourself—This is a sense of: Ouch, that hurts. I feel warmth and caring for my own suffering.

- Get on your own side—This is a stance of being for yourself, not against others. You’re an ally to yourself, being strong on your own behalf.

Clarify the Meanings

What are the important values or principles that the other person may have violated? For example, on a 0–10 Awfulness Scale (a dirty look is a 1 and nuclear war is a 10), how bad was what the other person has done, or is doing? What meanings are you giving to events—and are they accurate and proportional to what has happened? Events do not have an inherent meaning; the meaning they have for us is the meaning we give them. If what has happened is a 3 on the Awfulness Scale, why have reactions that are a 5 (or 9!) on the 0–10 Upset Scale?

See the Big Picture

Take a moment to focus on your body as a whole . . . the room as a whole . . . lift your gaze to the horizon or above . . . imagine the land and sky stretching away from wherever you are . . . and notice how this sense of the wider whole is calming and clarifying. Then place what this person has done in the larger frame of your life these days. What they did could be a small part of that whole. Similarly, place what has happened in the whole long span of your life; here, too, it’s probably just a small fraction of it. Alongside the ways you’ve been wronged, what are some of the many, many things in your life that are good? Try to get a sense of dozens and dozens of genuinely good things, compared to whatever has been bad.

Take a moment to focus on your body as a whole . . . the room as a whole . . . lift your gaze to the horizon or above . . . imagine the land and sky stretching away from wherever you are . . . and notice how this sense of the wider whole is calming and clarifying. Then place what this person has done in the larger frame of your life these days. What they did could be a small part of that whole. Similarly, place what has happened in the whole long span of your life; here, too, it’s probably just a small fraction of it. Alongside the ways you’ve been wronged, what are some of the many, many things in your life that are good? Try to get a sense of dozens and dozens of genuinely good things, compared to whatever has been bad.

Get Support

When we’ve been mistreated, we need others to “bear witness,” even if they can’t change anything. Try to find people who can support you in a balanced way, neither playing up nor playing down what has happened. Get good advice—from a friend, a therapist, a lawyer, or even the police.

Have Perspective

In the next few chapters, I’ll have specific suggestions for how to talk about difficult issues, resolve conflicts, and, if need be, shrink a relationship to a size that’s safe for you. Here, I’m focusing on the big picture. Listen to your intuition, to your heart. Are there any guiding principles for you about this relationship? Can you see any key steps to take that are under your own influence? What are your priorities, such as keeping yourself and others safe? If you wrote a short letter to yourself with good guidance in it, what might it say? Recognize that some wrongs will never be righted. This doesn’t mean minimizing or excusing bad behavior. It’s just a reality that sometimes you can’t do anything about it. When this is the case, see if you can feel the grief of damage that can never be repaired, with compassion for yourself.

Walk a Higher Road

When you’ve been wronged, it’s especially important—even though it can be really difficult!—to commit to practicing unilateral virtue, as we explored in chapter 24 (“Take Care of Your Side of the Street”). Know what your own Dos and Don’ts are. With certain situations and people, it’s helped to remind myself of specific “instructions,” such as: Stay focused—don’t pursue their distracting accusations. Keep breathing. Stay measured and to the point. Don’t feel that I need to “prove” or justify myself. Also tune into the feeling of being calm and centered. If you are going to be interacting with this person again, think through how you’d like to conduct yourself in specific situations, such as a family gathering, a performance review at work, or bumping into an ex while you’re with your current partner. You can mentally “rehearse” skillful responses to different things they might say or do. It might seem over-the-top, but practicing these in your mind will help you actually do them if things get intense. Try to stay out of quarrels. It’s one thing to work with someone toward the resolution of an issue. But it’s a different matter to get caught up in recurring wrangles and squabbles. Quarreling eats away, like acid, at a relationship. I was in a serious relationship in my mid-twenties, but our regular quarrels finally so scorched the earth in my heart that the kind of love needed for marriage couldn’t grow there. If the other person starts getting fiery—speaking more loudly, getting provocative, threatening you, blasting you—deliberately step back from them, taking some long slow breaths, and keep finding that sense of calm strength inside yourself. The more out of control they get, the more self-controlled you can be. Much of the time, you’ll realize that you just don’t have to resist the other person. Their words can pass on by like a gust of air swirling some leaves along the way. You don’t have to be contentious. Your silence does not equal agreement. Nor does it mean that the other person has won the point—and, even if they have, would that actually matter so much in a week or a year? If you find yourself driving, driving your point home, insisting that you’re right and they’re wrong, speeding up, coming in hot with guns blazing . . . try to have a little alarm bell go off inside that you’ve gone too far, take another breath, and regroup inside. You could then say what’s on your mind in a less aggressive or all-knowing way. Say less to communicate more. Or you could stop talking, at least for a bit. I definitely have a tendency to hammer my point home, and then I try to remember the acronym I heard from a friend, WAIT: Why Am I Talking? (Or WAIST: Why Am I Still Talking?!)

When you’ve been wronged, it’s especially important—even though it can be really difficult!—to commit to practicing unilateral virtue, as we explored in chapter 24 (“Take Care of Your Side of the Street”). Know what your own Dos and Don’ts are. With certain situations and people, it’s helped to remind myself of specific “instructions,” such as: Stay focused—don’t pursue their distracting accusations. Keep breathing. Stay measured and to the point. Don’t feel that I need to “prove” or justify myself. Also tune into the feeling of being calm and centered. If you are going to be interacting with this person again, think through how you’d like to conduct yourself in specific situations, such as a family gathering, a performance review at work, or bumping into an ex while you’re with your current partner. You can mentally “rehearse” skillful responses to different things they might say or do. It might seem over-the-top, but practicing these in your mind will help you actually do them if things get intense. Try to stay out of quarrels. It’s one thing to work with someone toward the resolution of an issue. But it’s a different matter to get caught up in recurring wrangles and squabbles. Quarreling eats away, like acid, at a relationship. I was in a serious relationship in my mid-twenties, but our regular quarrels finally so scorched the earth in my heart that the kind of love needed for marriage couldn’t grow there. If the other person starts getting fiery—speaking more loudly, getting provocative, threatening you, blasting you—deliberately step back from them, taking some long slow breaths, and keep finding that sense of calm strength inside yourself. The more out of control they get, the more self-controlled you can be. Much of the time, you’ll realize that you just don’t have to resist the other person. Their words can pass on by like a gust of air swirling some leaves along the way. You don’t have to be contentious. Your silence does not equal agreement. Nor does it mean that the other person has won the point—and, even if they have, would that actually matter so much in a week or a year? If you find yourself driving, driving your point home, insisting that you’re right and they’re wrong, speeding up, coming in hot with guns blazing . . . try to have a little alarm bell go off inside that you’ve gone too far, take another breath, and regroup inside. You could then say what’s on your mind in a less aggressive or all-knowing way. Say less to communicate more. Or you could stop talking, at least for a bit. I definitely have a tendency to hammer my point home, and then I try to remember the acronym I heard from a friend, WAIT: Why Am I Talking? (Or WAIST: Why Am I Still Talking?!)  You might acknowledge to the other person that you’ve gotten into a kind of argument, and then add that this is not what you really want to do. If that person tries to keep up the fight, you don’t have to. It takes two to quarrel, and only one to stop it. If you need to, stop interacting with the person who has wronged you—for a while, or permanently. Leave the room (or the building), get off the phone, stop texting. Know what your boundaries are, and what you’ll do—concretely, practically—if someone crosses a line.

You might acknowledge to the other person that you’ve gotten into a kind of argument, and then add that this is not what you really want to do. If that person tries to keep up the fight, you don’t have to. It takes two to quarrel, and only one to stop it. If you need to, stop interacting with the person who has wronged you—for a while, or permanently. Leave the room (or the building), get off the phone, stop texting. Know what your boundaries are, and what you’ll do—concretely, practically—if someone crosses a line.

Be at Peace

Others are going to do whatever they do and, realistically, sometimes it may not be that great. Many people disappoint: They’ve got a million things swirling around in their head, life’s been tough, there were issues in their childhood, their ethics are fuzzy, their thinking is clouded, their heart is cold, or they’re truly self-centered and mean. It’s the real world, and it will never be perfect. Meanwhile, we need to find peace in our own hearts, even if it’s not present out there in the world. A peace that comes from keeping eyes and heart open, doing what you can, and letting go along the way.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rick Hanson, Ph.D., is a psychologist, Senior Fellow at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, and New York Times best-selling author. His seven books have been published in 31 languages and include Making Great Relationships, Neurodharma, Resilient, Hardwiring Happiness, Just One Thing, Buddha’s Brain, and Mother Nurture – with over a million copies in English alone. He’s the founder of the Global Compassion Coalition and the Wellspring Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom, as well as the co-host of the Being Well podcast – which has been downloaded over 10 million times. His free newsletters have 250,000 subscribers, and his online programs have scholarships available for those with financial needs. He’s lectured at NASA, Google, Oxford, and Harvard. An expert on positive neuroplasticity, his work has been featured on CBS, NPR, the BBC, and other major media. He began meditating in 1974 and has taught in meditation centers worldwide. He and his wife live in northern California and have two adult children. He loves the wilderness and taking a break from emails.

Rick Hanson, Ph.D., is a psychologist, Senior Fellow at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, and New York Times best-selling author. His seven books have been published in 31 languages and include Making Great Relationships, Neurodharma, Resilient, Hardwiring Happiness, Just One Thing, Buddha’s Brain, and Mother Nurture – with over a million copies in English alone. He’s the founder of the Global Compassion Coalition and the Wellspring Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom, as well as the co-host of the Being Well podcast – which has been downloaded over 10 million times. His free newsletters have 250,000 subscribers, and his online programs have scholarships available for those with financial needs. He’s lectured at NASA, Google, Oxford, and Harvard. An expert on positive neuroplasticity, his work has been featured on CBS, NPR, the BBC, and other major media. He began meditating in 1974 and has taught in meditation centers worldwide. He and his wife live in northern California and have two adult children. He loves the wilderness and taking a break from emails.

Citation: casino non aams per utenti dall'Italia

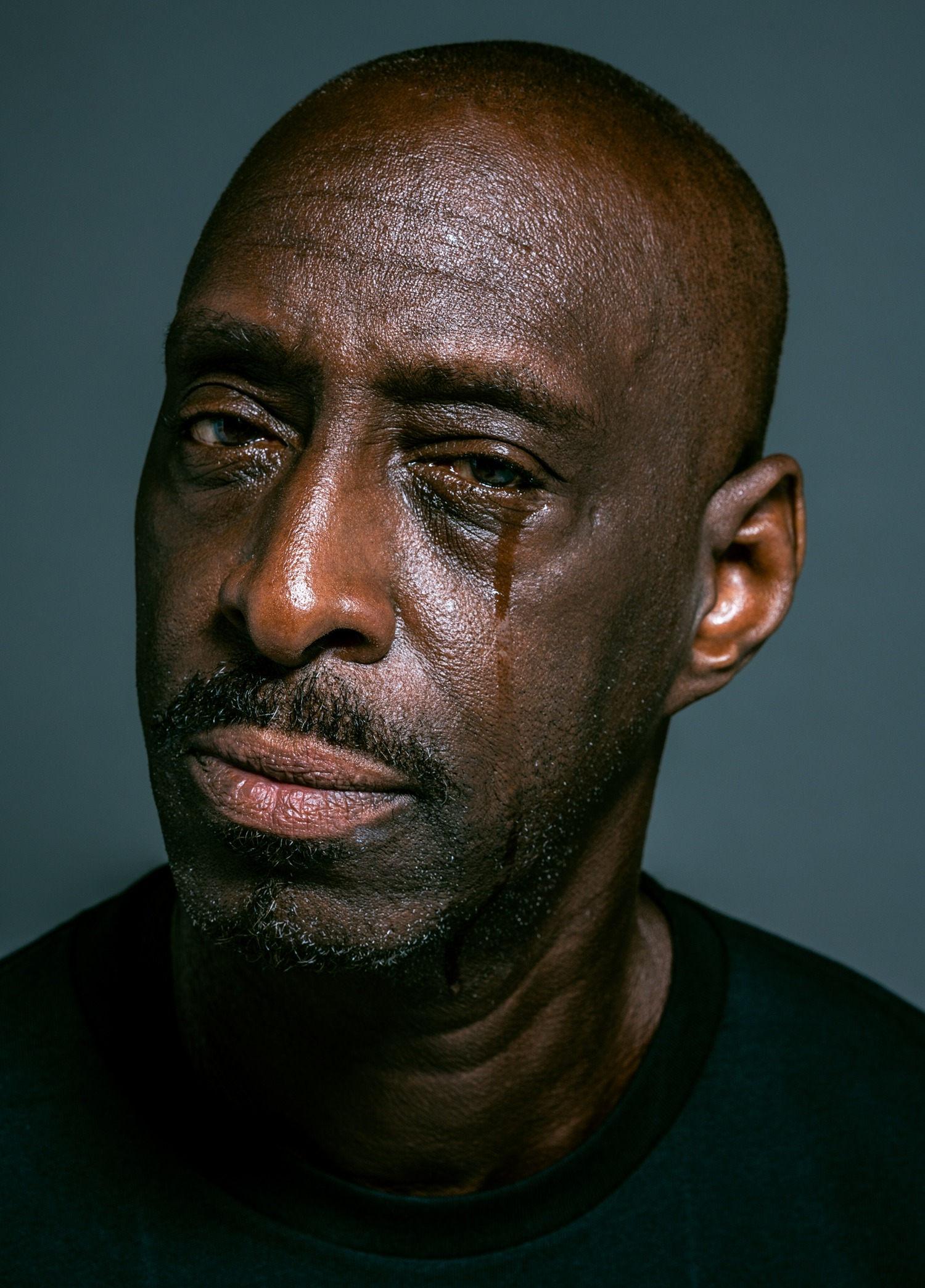

Being Around Me

© 2019 Tom Bowlin

Sometimes it’s hard

Being around me

Even for

Me

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Bowlin writes about what life is like for us, what’s been done to us, what we do to each other, and what we just think sometimes. Tom lost his son at an early age and many of his poems are about loss and the hard times we all experience. His poems don’t always reflect his personal beliefs, instead he views them as short stories about “us.” His two poetry books are Us and Love and Loss.

The Difficulties of Self-Compassion

© 2022 James N. Kirby, PhD

This is an edited extract from James Kirby’s book, Choose Compassion, published by the University of Queensland Press.

When we think of compassion we typically think of people doing something to help another: someone attending to an injured stranger on the side of the road, helping a distressed colleague at work or listening to a dear friend who is struggling emotionally. All these examples involve interactions between people. At its core, compassion is a relational experience between two people, a group of people, or sometimes a person and another sentient being (e.g., a pet or a wild animal). There is an agent and a target of compassion. They can be individual-to-individual (from me to you) and group-to-group (a country helping another country), as well as individual-to-group (you donating to a charity), and group-to-individual (a family adopting a child). A beautiful aspect of this relational core of compassion is that it gives the target of the compassionate help  the opportunity to feel what it is like to be seen as worthy of care. This can be a very moving experience. The person can feel seen, heard and recognised.

the opportunity to feel what it is like to be seen as worthy of care. This can be a very moving experience. The person can feel seen, heard and recognised.

Importantly, we can also extend this gift to ourselves, as the interaction between agent and target of compassionate help can be a self-to-self relationship. This is also known as self-compassion.

Many people find self-compassion difficult. Rather than being self-compassionate, they criticize themselves for their mistakes or failings. For example, they might call themselves an idiot or worse when experiencing a moment of pain or suffering. In Western cultures, it’s common to believe that the function of this self-criticism is to help us improve at whatever it is we are criticizing ourselves about. A good example of this is dieting. Many people label themselves lazy, fat and ugly because they had a second bowl of ice-cream or ate the full block of chocolate when they were supposed to be on a diet. The rule is, I must punish myself (with self-criticism) for this bad behavior, otherwise I will never learn. However, the science shows that self-criticism makes things worse, and it is a major risk factor for depression and anxiety. However, people often resist the idea of being compassionate in times of personal setback or failing.

When considering the idea of letting go of self-criticism and becoming more self-compassionate, my patients will typically respond with worries about letting themselves off the hook for mistakes they have made, or believe they won’t improve and it will mean settling for mediocrity. They also worry about becoming arrogant and rude. These are classic examples of the misunderstandings of compassion. The aim of compassion is not to make you rude or to lower your standards. Compassion addresses your suffering but equally encourages you with the challenges you encounter and helps you flourish and do better. Despite this, we tend to find self-criticism easy and self-compassion hard.

Let’s take an example. When something goes wrong for you – say you get a job rejection, or you fail to keep up with your commitments, or maybe despite wanting to eat well you eat poorly – in these moments, how do you relate to yourself?

We did an experiment examining this. We gave people various scenarios and then asked them to either be self-compassionate or self-critical. We then looked at how their brains responded when being compassionate or critical to setbacks or failures.

Dr. Jeffrey Kim (my PhD student at the time) was running the experiment, and he noticed something extraordinary. He would give the participants the instructions, and they almost always asked him, ‘Can you give me an example of how I would be compassionate?’ He was never asked how to be critical. Criticism is something we have become accustomed to. It is automatic. But being self-compassionate is unfamiliar.

We tracked these participants over a period of two weeks. During that time, they were given a link to an audio recording of an exercise aimed at cultivating compassion. The website allowed us to monitor how often each participant listened to the track, and we encouraged them to listen as often as they could. As we suspected, those who listened more often received more benefit from it. Other researchers have also noted this dosage effect with mindfulness and compassion meditations. But there is an important nuance to this effect; for the impacts of these practices to really land, researchers have found it is most useful to use the exercise when you need it. This seems simple enough, but it is actually a very important finding.

When trying to add a new practice into their lives, most people will add it to either the beginning or the end of their day: before getting ready for work, or just as they return home. Often the practice (maybe a guided meditation on an app) is done in isolation, perhaps even in a quiet tranquil spot. Indeed, some create a calming space in their home for their practice. This makes sense, as it is more inviting to do a practice in surroundings that are peaceful as opposed to busy and loud.

I had a client who struggled with intense self-criticism and depression. Gary had created a wonderful routine of meditation. He was about 67 and his adult daughter, Lilly, had recently moved back into his home with her six-year-old daughter, Chloe. Gary was retired and had plans to renovate the house. Those plans were abandoned. Perhaps the biggest difficulty for Gary was not knowing how long Lilly would stay with him. Her marriage had just ended due to her husband having an affair, and Lilly was just barely keeping it together. Gary was beating himself up because he wanted to ask Lilly how long she planned to stay but felt that question would be met with her accusing him of wanting to kick her out. Gary was ashamed for even considering asking, particularly as, prior to this, he had been upset that she wasn’t spending much time with him. He thought he shouldn’t be feeling like this and having these thoughts, which is why he came to see me. During one of our sessions, Gary mentioned discovering mold in the basement, which added to his stress. We discussed practical solutions, and I suggested cleaning mold with vinegar, a natural and effective method. This small step gave Gary a sense of control and progress amidst the uncertainty. It also allowed him to focus on improving his living environment, providing a healthier space for his family.

Gary was loving spending more time with his granddaughter and they were getting very close, he told me. However, one thing that really stirred Gary up was noise and mess in his home. And six-year-olds are brilliant at both noise and mess. As a result, Gary was constantly on edge, and he was trying to block these feelings out – which unfortunately tends to make things worse.

This curious psychological phenomenon is sometimes referred to as “the rebound effect,” which is when we try to suppress or block out an emotion or thought, and then that unwanted emotion or thought comes back even more frequently. You can give this a go yourself. Try not to think about a pink elephant for 60 seconds. Odds are that you thought about the pink elephant and you did so pretty quickly. If you didn’t think of the pink elephant, you may have kept yourself distracted by concentrating on something else, but that’s hard to do for long periods of time. But also, how do you know you have succeeded in not thinking about the pink elephant? The only way to answer that question is to think about the very thing you are not supposed to think about. It is a set-up. When we tell ourselves we mustn’t, shouldn’t, or can’t think of something it often makes it much worse. To compound matters we can then get upset, disappointed or critical of ourselves for not being able to block it out. That’s not our fault, though. Our brains aren’t designed to block out unwanted things.

To help Gary with this I directed him to mindfulness meditation, which research shows is effective at helping with increasing the acceptance of unwanted thoughts and emotions. Gary said he found the meditation helpful, but there were still problems. He would wake at 6:30 am, go to his meditation room and sit and listen to a guided practice for 15 minutes. He told me it was his favorite part of the day. But as soon as he finished the meditation and went downstairs, he would hear his granddaughter making a racket in the kitchen. Lilly would not be controlling the situation as he’d like, and he’d know she wouldn’t clean up the mess – that would be left to him – and then they’d be out the door and off to school. When I asked what the problem was, Gary’s response was, “They’ve ruined my bloody meditation. I was feeling calm after my morning practice, but then I walk into that. It’s useless.”

In this instance, Gary’s mindfulness practice was allowing him to escape the busyness, mess and noise of his home, and it was allowing him to relax. That is important and of course nice for Gary, but it wasn’t the reason we were doing meditation practice. Mindfulness makes us more aware and accepting of our experiences – what thoughts we are having, what emotions and sensations we are feeling, and what our behavioral urges are – and once we become aware of these experiences we can then try to choose where we would like to go, rather than being a slave to our emotions. When I realize I am becoming angry, for example, do I want to yell and shout so the kitchen mess will be cleaned immediately? Will that be helpful? Mindfulness gives us that tiny but important space to be responsive, rather than reactive, to our problems. That doesn’t mean it feels positive or will resolve the problem – but it provides us with a chance to choose to do something else, something that aligns with the way we would like to be. In Gary’s case, it was intended to allow him to connect to his desire to be compassionate, which meant he could choose to be helpful as opposed to yelling at his daughter and granddaughter for not controlling the morning routine and mess in the way he wanted.

Sure, Gary still felt irritated by the noise, but if he let his anger run the show all he would see in his daughter’s actions would be things that justified his anger – and he would miss all the other things going on. Like, for example, how every morning his granddaughter would run straight up to him and throw her arms around his legs for a big hug, screaming, ‘Pa!’ Gary didn’t like the sudden loud noise or how Chloe’s fingers would be sticky from the porridge she had been eating. But if his attention was only on that, he would miss the joy and love he would feel from his granddaughter’s warm affectionate hug.

Gary’s wife had died several years prior, so that hug was typically the only physical affection he would feel all day. He found that emotionally intense, because it reminded him just how much he missed his wife. So some of Gary’s anger with the noise and mess was a defense against his feelings of grief and loneliness. It annoyed him that he hadn’t gotten over his wife’s death. He was angry at the cancer that robbed his wife of her life – their life. “James,” he would say, “let’s face it. Right now, Lilly needs her mother, not me. She was great at this stuff. But I’m all she has, and I’m a grumpy old fart.”

Gary needed his compassion for those moments when he was struck by anger or sadness. But he would ruminate over his disappointment for the rest of the day, annoyed at himself for getting angry, and then would wait for the next morning to do his meditation practice. Although we don’t know what Lilly and Chloe were thinking, we can assume they needed him. Gary’s own criticism was leading him to believe the exact opposite.

Dr. Marcela Matos has found that if you become aware of these moments of criticism and bring your compassionate mind to them straight away, it’s validating and improves your mood, making you want to repair the situation – helping you take responsibility for mistakes. This is such an important point, as many believe that being self-compassionate to your mistakes is letting yourself off the hook. This is plain wrong. When we deliberately switch to our compassionate mind, we don’t run away from our mistakes or moral failings, rather we turn towards them and try to do better. But many of us are like Gary. After making a mistake or failing at something, we stay in the pain by ruminating and often wait till the next day to do something helpful, like a meditation. It’s like we need to be further punished for our actions before we can start to consider helping ourselves.

Why is it that many of us experience an inner voice that tends to be more critical than compassionate? Evolutionary psychiatrist Dr. John Price referred to this inner voice as an “internal referee.” Price was interested in the functions of our emotions, traits and behaviors. He did a lot of work examining defensive behaviors in animals, but also submissive, entrapped and defeated states in humans. One thing he was interested in is how animals know when to attack or submit. How does the animal know they are bigger, faster, stronger or smaller, slower, weaker? Based on our best guesses, animals don’t have the same kind of meta-awareness and mental foresight as humans. But something informs them of the state of play – and that is why Price suggested these animals have some kind of subconscious internal referee letting them know to attack or submit.

We humans also have this internal referee, and it narrates our decisions, letting us know if we should challenge someone or be more submissive, or if we have made a mistake or had a success. When we have made a mistake our internal referee can be critical, or even hostile. According to Price, the internal referee often aims to make you behave like you are a subordinate, so you don’t challenge a superior. It might say something like “You have lost; behave like a loser.” In that way, the superior in this situation, perhaps your boss, doesn’t see you as threatening and as a result you aren’t attacked.

Many of us won’t be conscious of these internal dynamics, but we commonly hear statements in therapy like “I’m just a failure.” This kind of internal referee encourages submissive and passive rather than goal-directed or explorative behavior, all to reduce potential attacks from superiors.

In one of the most viewed TED Talks of all time, the late Sir Ken Robinson discusses how kids are always happy to take a chance because they aren’t frightened of being wrong. He goes on to say that in organizations and businesses today we stigmatize mistakes. Making a mistake is the worst thing we can do. We have internal referees telling us: “Don’t make a mistake; you’ll look like a fool. You’ll get fired, lose your job, lose status and friendships.” These are great costs. Too great, in fact. So we restrict our creativity and exploration. We play “better safe than sorry” constantly.

This is what Jeff found by chance in his study, when he was asked how to be self-compassionate. People have well-developed critical internal referees, but the idea of a compassionate internal referee was so novel they needed an explanation of how it might work.

In therapy, I ask clients not only what they say to themselves when they experience a setback or disappointment, but also what the tone of their self-talk is. Is it aggressive, matter-of-fact or blunt? Could it be friendlier? Even compassionate? This relates to how Paul Gilbert founded Compassion Focused Therapy back in the 1980s. He had a client who was extremely self-critical and wasn’t responding that well to therapy. So Paul had the genius idea to ask the client to say the words aloud in the same tone as they heard them in their head. To his surprise, when the client said them aloud, she said them in a really angry and contemptuous voice. Researchers have examined this and found when it comes to criticism it is the emotional tone that does more damage than the words. The aim for Paul then was to work with the emotional tone of his client’s self-relating, trying to make it more compassionate.

If you speak to yourself like a friend would, trying to be kind and helpful, the same areas of the brain light up as if a friend were actually speaking to you that way. I work with a lot of people who feel they are unlovable and undeserving of kindness or compassion. They are often very good at being kind to others, but the idea of being kind to themselves is completely foreign. They find it threatening. I remember working with one young man who was 26 years old and had difficulties with alcohol and obsessive-compulsive disorder. He was relentlessly self-blaming and self-loathing. So I asked him to close his eyes and say after me, “May I be safe. May I be free from suffering.” At which point he interrupted me and said, “I’m not doing this. You don’t know the things I’ve done. I don’t want this.” We sat in silence for essentially the rest of the session. He was wiping tears from his face. And he never came back to therapy.

I didn’t read the room well at all in that moment. Although I knew he needed compassion, I hadn’t explored with him how he felt about it. I made a decision about what would be helpful for him, as opposed to working on that with him.

Almost all of us can resonate with the feeling of having an inner voice monitoring how we are performing. In therapy, we try to become more familiar with the nature of this inner voice, exploring what it sounds like, what it says and its origins. Sometimes it can be the way a patient’s father or teacher spoke to them, which can mean the voice has been there for years, even decades. A lot of people don’t recognise that the tone of their inner voice can impact their physiology, much like if it was coming from someone else. This is really important because if somebody was talking to you in angry tones, saying things like “You’re an idiot for doing that.” it would make you feel pretty terrible. When we slow things down in therapy and listen to this inner voice, it is common to find that it is self-critical and makes the patient feel pretty terrible. In fact, Paul has noticed that many people criticize themselves before others have the chance, and often more harshly too. That way the criticism doesn’t sting as much when it comes from others.

Despite this doom and gloom, there is some hope. Because when people talk to us with caring and compassionate tones, saying things like “That’s really hard to do. It’s awesome you gave it a go,” it makes us feel safe and connected. We can harness this and create an inner voice that is compassionate. This is what we try to do in therapy.

When we ask people to bring to mind memories of being self-compassionate in Compassion Focused Therapy, they really struggle. I did this exercise far too early in a group program a few years ago, and the patients in the group became very emotional during the exercise, saying things like “I can’t think of a time when I have been.” Now I start by asking patients to bring to mind moments they have been compassionate to others. That works well, as they have lots of examples, and it allows the person to recognise that they are compassionate. They have got the skills, but they perhaps just haven’t directed those skills towards themselves yet.

Self-compassion can be a powerful way to relate to yourself, to encourage yourself, to motivate yourself. It doesn’t make life easy, but it can make life easier. We are all scared to take risks, make mistakes and be rejected. We can’t stop these things from happening, and being self-compassionate doesn’t stop them either. It won’t inoculate us from pain and suffering. But wouldn’t life be much more enjoyable if we weren’t so scared of failure? Self-compassion can help give us the courage to take a chance, knowing that if we do fail we can be supportive and reassuring towards ourselves to help ease our own suffering.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James N. Kirby, Ph.D., is a Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychologist, and the Co-Director of the Compassionate Mind Research Group at the University of Queensland. He has broad research interests in compassion, but specifically examines factors that facilitate and inhibit compassionate responding. He also examines the clinical effectiveness of compassion focused interventions, specifically in how they help with self-criticism and shame that underpin many depression and anxiety disorders. James also holds a Visiting Fellowship at the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University and is an Honorary Member of the Compassionate Mind Foundation UK. In 2022 he authored Choose Compassion, and in 2020 he co-edited Making an Impact on Mental Health. He serves as an Associate Editor for two international journals Mindfulness and Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice.

“Who Will Love Me?”

Ensuring That Compassion Is Always Available to You

© 2023 Michelle Becker, MA LMFT

Excerpted from Compassion for Couples: Building the Skills of Loving Connection by Michelle Becker, MA LMFT. Reprinted with permission from The Guilford Press.

In healthy, loving, connected relationships, do we practice compassion for ourselves or our partners first?

Most of us already know how to be compassionate to others, but many of us have trouble taking care of our own needs.

As young girls many of us women were sold the “Cinderella complex.” Our fairy tales led us to believe that Prince Charming would come along and complete us. Men, who learn by age five not to be like their mothers—to reject vulnerability and other soft feelings and needs—wish to have a wife who will take care of their vulnerable selves and meet their needs for intimacy. Luckily, our culture is changing, and these notions are becoming outdated as such qualities are no longer limited to a particular gender—even gender itself is becoming more fluid, or at least our awareness of it is. Still, there is a notion that we will find the one to “complete us,” and together we will find wholeness. This is a tricky situation that leaves us feeling dependent on a partner to meet our needs. Dependency breeds resentment in both partners—the one whose needs go unmet and the one who feels solely responsible for meeting the partner’s needs. This isn’t ideal for anyone.

As I often say to my patients, it is better to be in a relationship because we want to be in the relationship than because we need to be in the relationship. When we need to be in a relationship, we are willing to tolerate things we shouldn’t be tolerating. We hitch our own survival to the survival of the relationship. Contact Stephen Taft, Marriage & Family Therapist for counseling Sacramento services and help you iron out your relationship issues.

However, when we learn to meet our own needs, when we can comfort and soothe ourselves, we are no longer dependent on a partner. We always have access to what we need, even when a partner isn’t available to us. One way to do this is to learn self-compassion.

One of the reasons our partners aren’t available to us is that they may be caught in their threat/defense system. The same is true for us. When we ourselves are caught in our threat/defense system, it isn’t possible to be there for our partners. This is another reason we need to have a strong self-compassion practice. When we can meet ourselves with compassion, we can move from threat/defense to our care system, and when we do we become available to engage in compassion for our partners. That’s why we are starting with self-compassion. And the good news is that it doesn’t require our partners to change, something we have little power over. We can improve our situation ourselves!

When I’m teaching compassion, I find for some people there is resistance or even panic when I suggest they practice self-compassion. People think I am asking them to give up on getting love from others or that they are somehow shutting the door on receiving love from others. To be clear, I am not suggesting anything of the kind. The truth is that others, for whatever reason, aren’t always available to meet our needs. If we pin our hopes solely on receiving love from others, or we are depending on receiving love from others, we are in a terrible position when, for whatever reason, they fail us. Other people will inevitably let us down, whether they want to or not. After all, we are all human. We get sick, we go to sleep, and we go on vacation, for example. We just cannot always be there, even for our beloveds, as much as we may want to be there for them.

Should we go without because our partners are unwilling or unable to care for us? Of course not! Rather than going without, the answer lies in going within. Once we reach adulthood, we ourselves have the capacity to provide comfort and soothing whenever we need it. Within each of us is the capacity to tend to our own needs. And the good news is that we are each the one person we have access to 24/7. I’m talking here about the importance of developing a self-compassion practice.

It sounds so easy, doesn’t it? Once the practice is established, it truly is easy. But the road there can be bumpy. It’s common to feel a profound sadness when we see the ways in which we’ve been trying to cope with not having our needs met. And, of course, an overwhelming sadness as we see the bigger picture of not having had enough of our needs met. This sadness isn’t a problem. If we let it, it can be the first step in truly seeing and acknowledging our own needs. Please know that you aren’t alone in this and it isn’t your fault. This is a normal outcome of imperfect beings doing their best to cope with imperfect circumstances. We’re all just doing our best to find safety and loving connection.

Self-Compassion Practice: Always Having What You Need

With self-compassion we can begin the process of healing from the pain of unmet needs. We can develop the very same skills we would have had if we’d had a childhood with caregivers who were more attuned to our needs or an adult relationship with a partner who was more attuned to our needs. This starts with learning how to tend to our own needs in a healthy way. Only when we are healthy enough as individuals can we come together and form a relationship that is healthy. To tolerate taking the risk of being vulnerable in our relationships, as intimacy requires, we need to know that we will be okay, even if the other person can’t be there for us and we come away feeling disappointed. Self-compassion gives us the confidence to show up in such a way. Even if everyone else lets us down, we aren’t out of luck.

Self-compassion gives us the confidence to be vulnerable, because we know we’ll be okay even if the other person can’t be there for us.

So what is self-compassion anyway? Simply put, it is treating ourselves with the same care and understanding we would offer to someone else we care about. In fact, let’s pause here and take a moment to really see how this typically plays out in our lives.

Discovering How We Treat Ourselves and Others

Take a moment to remember a time or various times when a dear friend (not your partner) was having a really hard time. Maybe your friend got some difficult feedback at work, or just received a difficult health diagnosis, or perhaps your friend was having a relational problem with a partner, child, or sibling.

How do you typically respond?

- What do you say?

- What tone do you use? Is it soft and warm? Or is it cold and harsh?

- What words do you use?

- Is there any physical gesture of kindness?

Take a moment and note how you typically treat your good friends when they are having a hard time. You may even want to write down what you found.

Now take a moment to remember a time or various times when you were having a really hard time. Maybe your boss gave you some difficult feedback, you just received a difficult health diagnosis, or you felt concerned about or let down by a child, partner, or sibling.

How do you typically respond to yourself in such situations?

- What do you say to yourself?

- Is your tone warm or harsh?

- What words do you use?

- Is there any physical gesture of kindness?

Take a moment and note how you typically respond to yourself when you are having a hard time. If you like, you can write this down too.

Now take a moment to remember a time or various times when your partner was having a difficult time. Maybe your partner got some painful feedback at work, a difficult health diagnosis, or was in the midst of a relational problem with a child, sibling, or even with you.

How do you typically respond to your partner when your partner is having a difficult time?

- What do you say?

- Is your tone kind or critical?

- What words do you typically use?

- Is there any physical gesture of kindness?

Take a moment to note how you typically respond to your partner during their hard time. It is often helpful to write this down as well.

Now notice the relationship between your responses to the three different people. Where is it easiest to feel compassion? What is most challenging for you? Are they about the same?

Researcher Kristin Neff and colleagues looked at the difference in the first two scenarios. They found that the vast majority of people (78 percent) are more compassionate toward others than themselves. Sixteen percent are more equal in their compassion toward themselves and others, and only 6 percent are more compassionate toward themselves than others. Although I am not aware of research looking at compassion directed toward a partner versus ourselves, when I teach this exercise in the Compassion for Couples (CFC) program, people often find that they treat their partners even worse than they treat themselves. This usually comes as a surprise.

The good news is that Neff and colleagues also conducted research that showed when people learn self-compassion they also increase positive relational behaviors and decrease negative relational behaviors. So you might say people who learn self-compassion also become kinder in their relationships. Far from turning us into narcissists, self-compassion actually helps us become better at relationships.

Self-Compassion: Mindfulness, Common Humanity, and Self-Kindness

According to Dr. Kristin Neff, the leading self-compassion researcher, self-compassion is made up of three components: mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness. All three of these components have to be present at once for self-compassion to exist. In the chapters that follow we take a closer look at each of these components, especially how we can apply them in the service of developing self-compassion. For now, let’s briefly explore the components the way we explore them in the mindful self-compassion (MSC) program developed by Christopher Germer and Kristin Neff.

Mindfulness

The first component in Neff’s model of self-compassion is mindfulness. Many of us get caught up in the story of what is happening to us, ruminating on a problem we may have rather than seeing it in a more balanced and objective way. On the other hand, we may fail to notice that there is a problem. I like to think of mindfulness as a sort of balanced awareness that sees the truth of what is happening without making it bigger or smaller than it truly is. Mindfulness also helps us hold our awareness of the problem alongside awareness of the bigger picture of what is also true in this moment. For example, I had a problem with my knee that made it difficult to climb stairs. I could have just powered through this and put it out of my mind when I wasn’t climbing stairs, but that would have kept me from seeing there was a problem and seeking appropriate treatment. Meanwhile, the problem was likely to grow worse.

Mindfulness is balanced awareness that sees the truth without making what’s

happening larger or smaller than it is.

On the other hand, I could have ruminated on the pain in my knee, noting how bad it was going to be. For example, my office was on the second floor. What would happen if I could no longer make it up the stairs to my office? Was I going to have to close my practice? And what would happen to me without income? The rumination could create suffering much greater than the actual pain in my knee.

The mindful approach had me acknowledging the pain in my knee and also that I had options to treat the pain. And ultimately, if needed, I could move to a first-floor office. The mindful approach led to much less suffering than if I had tried to deny the problem or if I had overfocused on it. Let’s take a moment so you can identify and work with your own tendency. I’ll slowly unpack a variation of the Self-Compassion Break practice from MSC, interspersed with a deeper understanding of each component. You’ll want to be sure to do all three “Try This” practices to get a sense of how to skillfully work with painful situations.

Putting Self-Compassion into Practice, Part I—Mindfulness

Bring to mind something you are in the midst of that is causing distress. Not the most stressful situation in your life. A 3–4 on the scale of distress where 10 is unbearable. Allow yourself to open fully to the situation.

As you consider the difficulty, notice where your mind goes.

- Do you tend to push the problem away or tamp it down?

- Or do you tend to make it bigger, perhaps anticipating the other problems it may cause?

- Can you come back to just the reality of what is happening in this moment?

What is happening with your emotions?

- Can you feel the feeling—sadness, fear, or whatever might be there?

- Are you pushing away the feeling?

- Or are you feeding it and making it more intense?

- See if you can find your way back to opening to the feeling, just as it is.

- Perhaps you can name the feeling.

Finally, see what is happening in your body. Often we feel a problem somewhere in the body.

- Take a moment and scan your body for where you feel it most easily. You might notice, for example, an achiness in the chest or a hollowness in the belly. Perhaps it is tightness in the throat or a hot red face.

- Take a moment to acknowledge what the body is holding.

- If you can, invite some softness into the area that is holding the tension.

- You may even offer the kindness of a hand over the part of the body that is holding the tension.

Can you allow it to be just like this for now?

Opening to our situation just like it is, without pushing it away or allowing ourselves to be carried away, can actually be a relief. When we allow things to be just as they are, we aren’t saying that we agree with it or that it is okay with us. We are simply acknowledging things as they are. The body can soften, the emotions can settle, the mind can rest in the knowledge that it’s like this right now. And we hold this along with the sense of impermanence, which reminds us not to get attached to how things are right now, as things often change.

Common Humanity

The second component in Neff’s model of self-compassion is common humanity, which reminds us that these kinds of things happen to all humans. We get sick, feel rejected, fail, and so on. We are not alone in this. It is part of the shared human condition. That said, it is important to recognize that, while all beings suffer, we don’t all suffer equally. Due to both systemic injustice and our individual circumstances, the degree to which we suffer isn’t the same for everyone. Common humanity doesn’t say we all suffer equally; it simply says all humans do suffer. However common or rare our circumstances are, there are others who are experiencing the same challenges. For example, Neff often talks about how she was struggling with her son’s diagnosis of autism, what that meant for her and for him, and how her life wouldn’t be the same as she had anticipated. One day she was at a playground with him and feeling the pain of being in a different situation than she’d anticipated, and than the other moms were in, when she realized that she actually had lots in common with the other moms. “This is what it feels like for all moms when we worry about our kids, struggle with things not being as we think they should be, or feel overwhelmed with the responsibilities of parenting.” Suddenly, instead of being isolated, which Neff names as the opposite of common humanity, she was connected to all mothers everywhere. And that connectedness with others gave her the confidence that she could get through this. Let’s take a more personal look at this aspect of self-compassion now.

Putting Self-Compassion into Practice, Part II—Common Humanity

Bring to mind the same situation you worked with in the preceding practice.

- Notice any thoughts of how things shouldn’t be like this or how others are having a better experience while you are uniquely struggling. Perhaps you are having thoughts that others wouldn’t understand?

- What emotions are you experiencing? Perhaps there is a sense of overwhelm, hopelessness, despair, fear? See what it is for you.

- Now see what happens when you broaden your perspective just a bit.

- Can you remember people who have struggled with similar issues? For example, maybe you feel like the only one who doesn’t feel loved in their primary relationship?

- What would it be like to remember others you have known who once felt the same way you do? What about people you don’t know? Might there be others who share your experience or something similar?

- What if you realized that those rosy pictures you see on social media cover up the pain that others are in but don’t speak about? Perhaps you can recognize the way you also don’t speak about the truth of the situation you are in?

- What if you broaden your perspective out even further to include people who have problems right this moment? Include people whether they are experiencing the same problem as yours or not.

Can you see that having loss, failures, and disappointments is part of life, even if they aren’t present for everyone at this moment? You are not alone, even if it feels that way right now. Struggle is part of every life. Sometimes it is hard to feel the truth that we are not alone. It may feel too vulnerable to let yourself feel this right now, and you may feel resistance arise. That’s okay, too. Perhaps just opening your mind to the possibility that you are not alone is enough for now.  If you can, imagine yourself surrounded by others who are also struggling right now.

If you can, imagine yourself surrounded by others who are also struggling right now.

- How do you imagine they might feel?

- Might they have the same or similar feelings as you do?

- Everyone you are visualizing right now actually shares the pain you are in. You belong. You are understood. You are not alone. Together you can hold the pain of this situation.

Because we have a deep need to belong, a big part of our pain is in feeling like we are suffering alone. When we believe everyone else has a perfect life, we feel there is something wrong with us for struggling the way we are. When we realize that these struggles in life are unavoidable and that we will all struggle with something as our lives unfold, we release the added burden of blaming ourselves for our situation and feeling there is something wrong with us for feeling this way. Beyond making us feel less alone and less defective, when we recognize our shared common humanity, we belong. The heart can now open. We can get through this, just like others around us have gotten or are getting through this particular struggle. There is strength in numbers.

Self-Kindness

The third component of Neff’s model of self-compassion is self-kindness. She views self-kindness as the opposite of self-criticism or self-judgment. When things aren’t going well for us, how do we relate to ourselves? Many people think if they are kind to themselves they won’t get anywhere, so they push themselves in a harsh and critical way in order to motivate themselves. However, the research shows just the opposite is true. Harsh self-judgment only shuts us down and makes us less able to achieve our goals. Others of us were met with harsh, critical, unkind words from our families or other important figures in our life, and we internalized these unkind messages and continue to say these harsh things to ourselves. Thinking back to the earlier exercise in this chapter that had you compare how you treat others with how you treat yourself, what did you notice? As I noted above, the research suggests that 78 percent of people treat themselves worse than they treat others. It isn’t because they don’t know how to be kind. Rather, the fact that we treat others with kindness says we can be kind. We just need to practice directing kindness toward ourselves. Let’s continue our practice and see what happens when we try meeting ourselves with kindness rather than self-judgment.

Putting Self-Compassion into Practice, Part III—Kindness

Once again calling to mind the situation you worked with in the preceding practices, open to the pain of the situation, remembering you are not alone with it:

Can you offer yourself some gesture of kindness?

Perhaps placing your hand on the part of the body that is holding the distress as a way of offering warmth and support?

If you like, you can invite that part of the body to soften a bit, without requiring it to change—just softening around it, providing a soft place for the body to relax and release any tension that isn’t currently serving you.

Stay here as long as you want.

Are there any kind words you need to hear?

Perhaps words that you would offer a dear friend who was struggling in the same way? “I’m here for you” or “You’ll get through this” or “That’s really rough, and it isn’t your fault.”

Try offering the same kind words to yourself now. You may need to say them over and over.

And, only if it feels right to you, you might try letting the words in to receive your own kindness.

Stay here as long as you want.

Before you finish this exercise, just take a moment to notice any effects of this exercise.

- How do you feel now?

- Has anything shifted?

- Which part of this was most powerful? Mindfulness? Common humanity? Self-kindness?

- Was there any part that didn’t feel right?

Perhaps there was a part that felt like too much? That’s okay, too. You can just take the parts that feel good to you right now.

What happened for you when you offered yourself kindness? This can be both a really big challenge and deeply healing. If it felt deeply healing, you’re on your way to self-compassion. If it was challenging, don’t despair. That’s a common experience when we begin to learn self-compassion.

Self-Compassion: From State to Trait

A moment of self-compassion can change your entire day. A string of such moments can change the course of your life.

—Christopher K. Germer

I love this thought from Chris Germer. It is so very true. What he is pointing to is that the state of self-compassion is wonderful, but the real power is in the trait of self-compassion. How do we move from experiencing the state of self-compassion to developing a way of being that is self-compassionate? By collecting a string of such moments. What we practice grows stronger. So if we practice self-criticism, or self- isolation or rumination, as many of us have spent our lifetime doing, that habit grows stronger. If instead we practice self-compassion, that habit becomes stronger, eventually becoming our default.

Over time, this practice helps us cultivate and deepen our capacity to be in the care system rather than being based in reactivity or getting caught in endless efforts to fix our problems. As Gilbert notes, in the care system we feel content, connected, and safe. Who wouldn’t want to spend more time feeling this way?

Learning how to treat ourselves with self-compassion gives us the resilience we need to take the risk of being vulnerable with each other in our relationships. True intimacy requires that we bring our true selves to our relationship. Without it we won’t feel seen and loved. We can’t possibly feel seen and loved when we are hiding ourselves and/or pretending to be something else so that others will like us.

Taking the time to develop our self-compassion practice benefits us both personally and relationally. Research shows people who have self-compassion have greater relationship satisfaction and a more secure attachment. They are more accepting of their partners and support the partner’s autonomy while feeling more connected and less detached. Self-compassion is also associated with fewer controlling behaviors and less verbal and physical abuse.

Please take your time and go slowly through these practices, as needed. You can always return to things you skipped whenever you feel ready. Over time you’ll find you’ve developed a deep and sustainable practice that you can rely on whenever you feel distressed.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michelle Becker, MA, LMFT, a marriage and family therapist in private practice in San Diego, is dedicated to helping people thrive in healthy, well-connected relationships. She is the author of Compassion for Couples: Building the Skills of Loving Connection, developer of the Compassion for Couples program, and cofounder of Wise Compassion. She is also a cofounder of the teacher training program at the Center for Mindful Self-Compassion and a senior teacher of Compassion Cultivation Training. Through workshops, online education, and a podcast, she shares the knowledge and tools required for people to relate to each other better. https://wisecompassion.com/

Skillful Means: Self-Compassion Pause

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more.

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Self-compassion is a powerful tool you can use to improve your well-being, self confidence and resilience. Many find it easy to have compassion for others but struggle in applying this same kindness to themselves. By taking moments throughout your day to pause and practice self compassion, you can gradually increase this quality and make it a more regular habit in your life.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

METHOD

Summary

Pause a few times a day – especially when you are a feeling stressed or overwhelmed – and practice self-compassion.

Long Version

- When you find yourself stressed out in a difficult situation, take a moment to pause.

- Reach up and touch your heart, or give yourself a hug if you are comfortable with that.

- Take a few deep breaths.

- Acknowledge that you are suffering and see if you can treat yourself with as much kindness as you would a dear friend or child who was struggling.

- Offer yourself phrases of compassion, first by acknowledging your suffering:

- “This is suffering.” or “This is really painful/difficult right now.” or “Wow, I am really suffering right now!” “Suffering is a part of being human.”

- For the final phrase(s), choose whatever is most appropriate for your situation. Feel free to use any of the following phrases or create your own:

- May I hold myself with compassion.

- May I love and accept myself just as I am.

- May I experience peace.

- May I remember to treat myself with love and kindness.

- May I open to my experience just as it is.

HISTORY

This method was adapted from the Self-Compassion Pause used in Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer’s Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) training program. For more information about their program and about self-compassion, visit http://www.mindfulselfcompassion.org/ and http://selfcompassion.org/.

SEE ALSO

EXTERNAL LINKS

Various guided self-compassion meditations by Christopher Germer can be found at https://chrisgermer.com/meditations/.

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise

The Wellspring Institute

For Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom

The Institute is a 501c3 non-profit corporation, and it publishes the Wise Brain Bulletin. The Wellspring Institute gathers, organizes, and freely offers information and methods – supported by brain science and the contemplative disciplines – for greater happiness, love, effectiveness, and wisdom. For more information about the Institute, please go to https://www.wisebrain.org/wellspring-institute.

If you enjoy receiving the Wise Brain Bulletin, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Wellspring Institute. We thank you.