News and Tools for Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 16.2 • April 2022

In This Issue

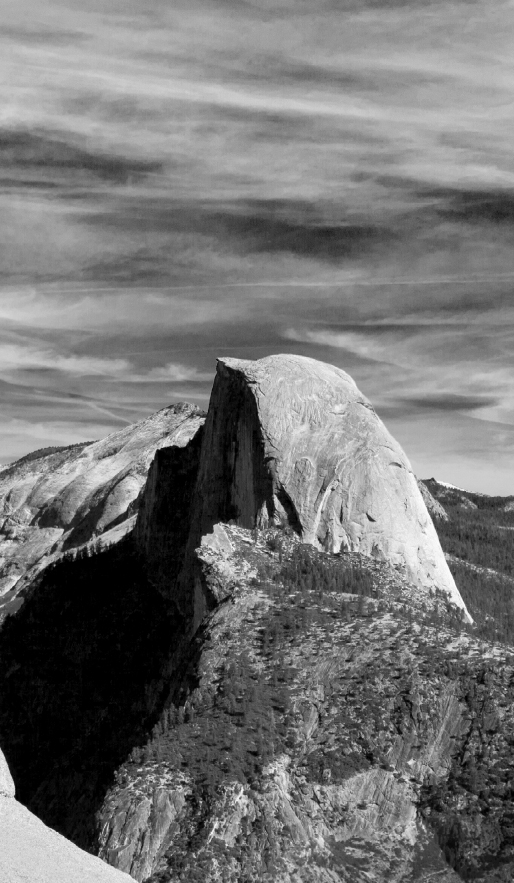

Tuolumne Triple

© 2022 Roddy McCalley

I wake with the sun, sky turning light behind a canopy of pines. Dan and Michelle are still in their sleeping bags. Leaving quietly, I drive to Tenaya Lake, park and head up the trail. Sun still behind the mountain, but almost immediately I am warm. Shouldn’t have brought the jacket, put it in the pack. After a mile or so I reach the north face of Tenaya Peak, 1,200 feet of gradually steepening granite slabs. Moving slowly but steadily, I pass several roped parties, and see three other unroped climbers who I gain on but don’t catch. It’s an hour to the summit, where I stop to eat a granola bar. To the southwest, the top of Half Dome marks the fold in the hills where Yosemite Valley is hidden. To the northeast, Fairview Dome gives away the location of Tuolumne Meadows, the other pole of the Yosemite climbing world. Many miles to go, and two more climbs: Matthes Crest and Cathedral Peak.

Though I will spend today alone, in communion with this place, climbing is the sacrament of my strongest friendships. Today is a moving meditation, and present in my practice are all the people with whom I have shared a rope. Some are ingrained in the way I move—Dan, probably drinking coffee by the meadow now, taught me to jam my hands and feet in cracks. Ethan, home in Joshua Tree with his family, has shown me again and again the power of balance and footwork. Fifteen years I have been climbing with them. Many others cross my mind as I cover this terrain—how many friends have I climbed Cathedral Peak with? Twenty? Thirty? More? Thankful for each of those days and each of those friendships.

Leaving Tenaya, heading east into the morning sun, I cross sandy hillsides with views south over the Merced River headwaters. Moving quickly, focusing on my feet, the mountains are abstract, a brushstroke on the horizon. As I pause to drink, my thoughts drift to a conversation I had with a fellow guide last summer about the rise of the online casino and how they’ve become a popular escape for many, much like these mountains are for me. He spoke of how, after long days on the trail, some of the crew would unwind by logging onto these platforms, finding a different kind of thrill in the virtual games. The memory brings the landscape into sharper focus—a slide down a snowfield, a carpet of flowers in a brief summer meadow, a plunge into clear cold water, a certain shade tree. Post Peak, Triple Divide Peak, the Clark Range, and the Lyell group, the familiar peaks of the high country where I worked as a backpacking guide for most of my thirties. Many summers in the folds of these mountains, each one filled with its own unique adventures, both physical and digital.

As I cross the ridge south of Tresidder Peak, the dramatic fin of Matthes Crest comes into view. The hillside steepens, can’t look around, don’t roll an ankle. No more wandering mind, focus on here and now. Sidestep, hand down, over the log, through the trees, into the meadow. Grass dry and firm, late summer, ferns starting to yellow. Silent creek bed, dry year.

Up the other side, breathing harder, pushing a bit for speed—chance of afternoon thunderstorms in the forecast, hoping to climb Matthes Crest before any buildup occurs. After that I can decide whether it’s safe to climb Cathedral. Just a few streamers of cloud, so far. I jog a bit on a sandy stretch, notice my heart rate is too high, slow down. Long day ahead. Find the right balance of speed and fluidity.

Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Michelle Keane edits the Bulletin, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online.

To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Climbing is the lodestar that pulls me towards healthy practices, away from excess. When I push my body in this way, I feel the effect of all that has come before. Through climbing, I’ve felt my body age, and learned to be careful. Forty-two years old and healthier than I was at thirty-two, though I have some pain in knees and shoulders. Twenty years working as a guide, carrying packs, coiling ropes. For years I drank, smoked, ate too much. But climbing is the greatest joy—this body, this muscle and bone, makes possible all the days of beauty and companionship. So I adapt. Climbing rewards good practices—I don’t drink or smoke anymore, and I am lighter and more balanced. I run in the mornings, and I feel stronger. I eat less sugar, and my stamina improves.

Dropping into the next valley I see a small lake, outlet stream silent this late in the season but visible as a sinuous curve through yellow meadow-grass and bracken. I jump from rock to log to avoid creating a new trail across the soft grass. Up the other side, steeper and steeper, the crest looming above. Weaving through small pines I flush a grouse, but it doesn’t go far, which feels right. Nothing to fear. It’s just me. I belong here too.

At the base of Matthes Crest, gusty winds race across the ridge and push cumulus towers through the sky above. The clouds are passing by, piling up on the Sawtooth Range many miles to the north. The coast seems clear enough, so I embark on the traverse. Immediately upon leaving the notch the route climbs several hundred feet to a knife-edge ridge. The exposure is extreme, but the climbing not too hard. Though I hustled all morning to get here, once on the crest I feel joyful, calm and unhurried. Every move is worthy of consideration, each new view worth stopping to savor.

A peregrine falcon sits on the next tower. I pause to look until it soars away to the east into shafts of sunlight, over the ridge and out of sight. I climb through, noting the accumulation of guano on its perch. I feel outside of myself, as though I’m merging with this place.

The crest goes on for most of a mile. Sometimes nothing exists but the rock in front of me. Other times I’m aware of the valleys on either side and the mountains beyond. The clouds pass on, and the high-altitude sun becomes fierce. I sit in a shady alcove to rest, drink water, eat one of the quesadillas I made the night before. There are two other climbers on the crest, a tall thin bearded man and his younger friend. They too are focused on the rock, and when I catch up with them the bearded man exclaims in surprise.

Eventually there is no more crest. The last tower gives way to a short fin like a miniature of the entire traverse, and then I am on slabs leading towards the Echo Peaks. I head around the eastern end of the Echo group, into a north-facing gully with one last lingering snowbank, across loose tilting talus and down to the grassy shore of Budd Lake. I dip my water bottles and drink, dip again. Wonder briefly if there might be Giardia in this water. Unlikely, up here. Not worth worrying about. The joy of drinking from a pure mountain lake far outweighs the small chance of an easily-cured illness that would not arrive for weeks anyway. We take far greater risks for lesser rewards.

Across the valley west of Budd Lake stands a shining beacon of white granite, the southeast flank of Cathedral Peak. I’m feeling tired now, but this is the most familiar part of today’s journey. I arrive at the trail. My feet know what to do now, I’m just floating along. As I climb the final switchbacks, a voice snaps me out of my reverie, saying my name. It’s Rob, who I last saw at the Needles, down by the Kern River, 8 or 10 years ago. We chat for a minute and I continue up the hill, realizing after a while that I should have told him to stop by the campsite later and say hi to Dan and Michelle. But I’m not in the world of people right now. I feel fuzzy around the edges; my feet sink just a bit farther into the earth than usual. My mind is slow, but my vision is very clear.

At the base of Cathedral is another familiar face. Chris was in this exact spot last time I was here, maybe a month ago. “Do you live here?” I say. We laugh and talk for a while. I’m feeling pulled upwards, and eventually I go. The clouds are still piled up on the northern skyline, and above me is blue sky.

As I climb this most familiar of routes, tired and elated, each tiny knob and edge is sharply in focus, and I am aware of the entire landscape around me. My borders are blurring; I flow effortlessly over the warm granite; I am part of it. My body is solid as rock and light as air. My often-busy mind is empty, and my heart is full.

Climbing has brought me great friendship and steered me towards good health, but what really captivates me and draws me back to the rock, again and again? It is this experience of purity and focus. I feel very small, yet one with the vastness and beauty around me.

I’m in no hurry to reach the end. Amazingly, no other climbers are in sight, though this is the most popular climbing route in the area. I stop on a ledge and take pictures looking up, down, and out. I feel very strongly that I belong here on this ledge. After a while I think of the summit, and continue up the last few hundred feet.

Near the top, I hear voices above. As I pull over the final headwall one of the voices says my name. Hey Roddy! It’s my friend Crystal, who wasn’t climbing until recently, recovering from shoulder surgery. It’s great to see her up here, and to meet her friend Sarah who I learn is also recovering from major surgery. All smiles, what a team!

We take summit pictures and I make conversation with half my mind, slowly emerging from my trance, still absorbed in the landscape. To the north I can see the green expanse of Tuolumne Meadows, center of the known world. Beyond it, the striking pyramid of Mt. Conness, which I’ve climbed by three different routes with four different partners. Matterhorn Peak farther north, lost in storm clouds but vivid in my mind’s eye—I crossed the ancient glacier to climb that peak with an old friend last month, and we shared a spectacular campsite by a stream clouded with glacial silt, spilling over a cliff into the deep green valley below. To the east I see the familiar slopes of Tioga Peak and Mt. Dana, and to the southeast Mt Lyell, which I climbed with my father years ago. Half Dome is now clearly visible to the southwest, and the brow of El Capitan peeking into view. Many weeks of my life on the side of that rock, many months in the valley below.

Directly west is the rocky descent I’d planned, past the Cathedral Lakes and down the steep slopes by Pywiack Dome to where my day began. Crystal and Sarah are hiking the trail down Budd Creek to Tuolumne Meadows, and offer me a ride from there to my car. I hesitate, tempted to spend another hour alone with this place, but then I thank them and accept. It will be nice to walk the trail with friends.

Gradually I let go of my attempt to drink in this landscape and become one with it. The world of people is my world. By the time we arrive at the road I am just me again. We drive to Tenaya Lake and jump in, and I’m shivering and hungry and human through and through. We all go back to camp, there’s room for one more car, we eat and play music and later Sarah suggests a walk into the meadow to see the stars and watch the lightning which is flickering cloud to cloud on the western horizon.

I sit apart from the others, just a bit. The cold of the night sky presses down on my body, heavy and tired. Beneath me the soil is warm, late summer, almost dry. I hear the river to one side, the road to the other. The voices of my friends wash over me and the edge of the meadow is outlined in treetops and starlight.

I will be in my sleeping bag later when the storm arrives. I will hold my bivy sack over my face to keep the water out, but some will trickle in around the edges. In the morning when I wake, my pillow will be soaked but warm from the heat of my body, and the storm will be a distant dream, like everything else but what is in front of me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Roddy McCalley grew up in Palo Alto, California. Family vacations were spent backpacking in the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada. After graduating from Yale University with a degree in biology, he spent many years leading outdoor education programs, with no fixed abode and all his worldly possessions in a Toyota Corolla. In 2009 he settled in Joshua Tree, where he teaches rock climbing during the fall-winter-spring season. He spends summers backpacking, climbing, and jumping in lakes in the Sierra. Playing in the outdoors has brought Roddy great happiness, and his work is to share that with others. If you’d like to learn about guided climbing adventures, visit www.climbwithroddy.com ...to learn about outdoor education programs for youth in underserved communities, please visit www.californiaore.org …and to see images and read more about all of the above, feel free to visit www.instagram.com/roddymccalley/.

Chances

© 2022 Jeanie Greensfelder

Each day I get another chance

to stay in the present moment,

to be grateful for being alive,

another chance to give up sugar,

another chance not to give up sugar,

to ponder on my prior selves,

recall teen dreams of fame,

clean-out closets, comprehend life,

spill milk, love it all,

to wonder who I really am,

earn my keep, value my body,

see with fresh eyes

the sun, stars, and moon,

be satisfied, bored, worthy,

smile at being human,

to have that hallmark day,

smooth and sublime, for when

I run out of chances.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeanie Greensfelder, a retired psychologist, volunteers as a bereavement counselor at Hospice of San Luis Obispo, CA, She served as the San Luis Obispo County poet laureate in 2017,18. Her books are Biting the Apple, Marriage and Other Leaps of Faith, and I Got What I Came For. Her poem, “First Love,” was featured on Garrison Keillor’s Writers’ Almanac. Other poems are at American Life in Poetry, in anthologies, and in journals. She seeks to understand herself and others on this shared journey. View more poems at jeaniegreensfelder.com.

Mindful Relating: How to Make Vulnerable Requests when our Ego is Tripped

© 2021 Danielle Ford

When I was in college, Michael, a good friend, came to me for advice on a situation that had me baffled. He was frustrated because his girlfriend wasn’t as affectionate as he was. To me, the solution was obvious - just ask her for what he wants! However, he was struggling with that idea - he felt that if she genuinely liked him, she would be doing those things automatically - he shouldn’t have to ask.

Ten years later, I was in a situation that made Michael’s struggle suddenly click for me. A man who I had recently dated, David, was acting as if I didn’t exist when we saw each other - looking through me as if I wasn’t there, approaching our group of friends and greeting everyone at our table. For me, the silent treatment is a real challenge - it doesn’t just hurt, it triggers PTSD flashbacks. I was livid - how could he treat me like this? He wasn’t just a random hookup! We’re friends! We care about each other! He knows I have PTSD and how harmful this behavior is for me!

It took me a while to realize I had unspoken expectations - I had a belief that respecting or caring about someone meant never giving them the silent treatment, so if he actually respected me, he wouldn’t ever give me the silent treatment. Under this logic, even “needing to ask” him not to do this would be proof he didn’t respect or care about me - or, taking it a step further, that I’m just not good enough to deserve basic respect from anyone. While the pragmatic part of me believed I should just tell him his behavior was a trigger and ask him not to do it, another part of me thought even talking about it would be proof I wasn’t really liked or respected.

In both Michael and my situations, we felt a basic definition of a relationship wasn’t being met - girlfriends show affection openly, friends who care never give each other the silent treatment. In both situations, we interpreted these actions as being about us - Michael’s girlfriend must not really love him, David must never have really respected me. In neither situation was there room for personal differences - maybe Michael’s girlfriend just didn’t like cuddling as much, but was crazy about him. Maybe David copes with sadness or emotionally ambiguous situations by withdrawing, but still cares.

This kind of indignation can also come up in situations where we don't feel fairly acknowledged or appreciated (“I shouldn’t have to ask them to say thank you. If they were actually thankful, they’d say it without me having to ask! Just having to ask is proof they don’t respect me!”), or if an unspoken boundary is crossed (“I shouldn’t have to tell them that kind of joke makes me uncomfortable, they should know jokes like that aren’t appropriate”).

In these situations, it’s possible that the other person cares and would want to help meet our needs. But our fears often sabotage our communication attempts. We may think - “if there is a ‘right’ way to be in relationship, they’re not doing it because they don’t actually respect/care about me” - which has the potential to make communication feel too risky.

It’s naturally really difficult to start a conversation - especially in a non-defensive way - when it feels like doing so might mean losing someone we care about. It can feel like we’re in a lose-lose situation, where, on a deep level, we believe we have to choose between a relationship we value, and having our needs met.

However, handled well, this is an opportunity to build our relationships. The truth is, most of the time, most of the people we are close to care about us and want to support us in our needs and our happiness. When we can share what is triggered in us and what we are needing in a non-attacking way, we can work together with our loved ones to create relationships that support everyone. But with the alarm bells going off, it’s really hard - almost impossible! - to let our guard down and share what we are feeling. What strategies might we use to help soothe our fears, be courageous, and open up?

First, we have to recognize that we are in this painful place. Then, it can be helpful to examine our internal narrative, which can take various forms, including:

Indignant Thoughts

Do we feel that something unnamed should be happening? That a certain behavior is should be automatic for friendship/relationship/respect? Are you interpreting something as proof you aren’t respected despite never having set a clear and specific boundary? (“I expect we’ll both be willing to have a conversation about a topic if either of us is anxious, ideally within a week of the issue being raised” is specific, whereas “You need to listen better!” is vague.)

Ambivalent thoughts and emotions

When we aren’t thinking about this particular event, we likely feel connected and positive about the relationship. However, when we try to figure out how to address the topic, our thoughts may turn to blaming and defensiveness. At its extreme, this can look like being convinced we need to end the relationship when we are angry and thinking about the situation, despite feeling fully committed when we are calm and thinking about other things.

Freeze and collapse responses

When we try to think of how we want to communicate around the topic, we get confused. Every imaginary conversation we play out in our heads ends badly, and we give up on deciding what to do. We may either end up repeatedly deciding we want to say something but never following through, or feeling like there’s nothing we can do and trying to push away thoughts on the issue.

Once we recognize that our egos might be tripped, we may be motivated to try to communicate in spite of the fear and anger coming up for us. Some helpful strategies for beginning the conversation:

Wait until you’re in a calmer, more connected place emotionally

Pause. Give yourself a break. Situations like this can feel urgent, but the truth is, this does not have to be fixed right away. The deeper something hits you, the more important it is to give yourself time and space. Resolve to only make decisions when you’re in a calmer headspace, one where you are still connected with the good and trustworthy aspects of your relationship, not in a headspace where all your mind can focus on is the negative situation at hand.

Do guided exercises around feeling safe

Situations that evoke the potential loss of an important relationship or touch deep inadequacy fears trigger our nervous systems. That is to say: even if you don’t have PTSD, you can still go into a physiological fight, flight, or freeze response in a situation like this. The self-protective “fight” response is what leads us to angry, blame-y, defensive thinking - after all, if they were a good friend and really cared, they would be doing (or not doing) this thing! When we, with great urgency, feel like we need to end a relationship, and there’s no point to even try to work things out, that is often our “flight” response being triggered. Feeling like “everything will end badly so there’s no point in trying” is a strategy from our “freeze” system. Even if we aren’t triggered to the point of hyperventilating, our fight/flight/freeze systems can influence our thoughts and decision-making.

Cultivating an internal sense of safety can reduce that sense of threat. Rick Hanson recommends a practice called “Notice you’re alright right now” - notice that right now, in whatever room you are in, you are safe, there is a lock on the door, you can breathe, you are well-fed. Feel it in your breath, in your toes - you are basically ok. Peter Levine recommends “orienting” - looking around the room and focusing on what is around you, which has been proven to calm the nervous system. I like to look up Yoga Nidra or Restorative Yoga classes on Youtube, both of which calm the nervous system and help my body feel safe.

Challenge the perception of distrust.

These questions are borrowed from an exercise on “assuming positive intent,” and they are a perfect fit to help challenge the fear and distrust that comes up in these situations. Grab a journal and answer:

a) What if they don’t know how this situation affects me?

b) Is it possible they would want to know, and would care if they knew this affects me negatively?

c) Could they be trying to find solutions, like me, but in a different way - what might those solutions be? What needs could they be trying to meet?

d) Is it possible they are right, competent, know what they’re doing, and still aren’t doing what I want?

e) Could they mean well, respect me, and have positive intent with their actions? What is a possible story that explains them acting this way and also caring about me?

Narrow down to the specific actions that would make you feel better.

Being clear on what you need to feel secure and respected helps keep the mind from getting caught in rumination.

It also makes it much easier for other people to give us what we need. Simply asking someone to “not ignore me,” “show more affection,” or “be grateful” are all vague. Does showing more affection mean being more receptive to your advances, making certain advances themself (hugging? cuddling?), or is verbal assurance enough? Does not ignoring you mean going out of their way to approach you and say hello, or simply saying hello if you happen to walk by each other, or is a simple ‘hello’ not enough and a 2-3 minute conversation what you need to feel acknowledged? In my case, I realized I would actually be fine with being treated as if I don’t exist (not making eye contact or greeting me) if the person doing that would let me know they need that space and promise to re-engage with me when they are ready.

When we’re upset, it’s easy to think what we want is obvious especially if we’re upset because someone is not doing something we feel they “should” be doing. However, our wants and needs are rarely as obvious as we might think, and the harder time we have specifying what we want, the harder it is for other people to give it to us.

A journaling technique that can help with finding clarity is writing yourself an apology or letter from the other person saying what you want them to say to you. On multiple occasions, this practice has helped me realize that what would make me feel better is different than what seems obvious in the situation.

Write out what you want to say while envisioning saying it to someone you feel deeply safe with.

Imagine you are in this situation with someone who you deeply trust and have no doubts about your relationship with, and write out what you would say to them.

For instance, a few months ago, I wanted to address a male friend who was making demeaning jokes about a female friend’s body. Every draft was along the lines of, “this is disgusting and sexist and anyone with any decency would know better.” Then I pretended another friend - one who I’ve had several conversations about sexism with and who has shown great integrity and compassion - was the person making these jokes, and how I would word it to him. It made a huge difference, and the resulting message was along the lines of, “I know you care about our friend and are probably just trying to be funny, but these make her uncomfortable, would you be willing to stop?” That message felt a lot better to send, and is much more likely to get a positive response.

Figure out how to make a communication opportunity controlled enough that you will actually follow through.

There are many different opinions on whether communication via writing or in person are preferable. I’ve noticed I am more likely to interpret written messages as being written in a negative tone of voice, and thus less likely to get upset when I can hear someone’s tone of voice - but in person, I am also more likely to freeze and not say everything I meant to. For me, in person is preferable if the conversation gets started and the other person is patient enough to let me get through everything I want to say (even with lots of awkward silences on my part), but sometimes I have to start the conversation in writing where I can make sure everything I want to say is written before I press “send.” If I am having a tough conversation in person, I always bring notes so anxiety doesn’t lead me to “forget” what I wanted to say.

This is highly individual. What will support you in being able to communicate what you need to? For the people who are able to communicate fluidly and without preparation, I commend and envy you. There is also no shame in not being able to communicate in a spontaneously skillful way - what supports your relationship most is figuring out what’s important to you and what questions you need to ask.

We all face situations with our loved ones that make us question if the relationship or that person is really as secure as we thought. “Would a friend really do this, would someone who loves me really not do that? Is this finally proof I’m not really good enough?” These situations can trigger fear and anger to the point where our desire to protect ourselves can harm relationships with people we care about. However, with courage, time, and care, we can learn to recognize when our egos are tripped, figure out how to communicate in a clear and non-blaming way, and use the situation to build even stronger relationships.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Danielle Ford is a software engineer and long-time meditation practitioner based in Denver, Colorado. Her passions include trauma work, self-compassion, and mindfulness practices, and she blends them to discover and develop daily life practices to help support herself and others in healing and finding freedom from suffering. Earlier in her career, she spent time building backend systems for educational tools—including one project where she had to explain concepts like RNG – co to znaczy to non-technical stakeholders, which helped shape the way she now communicates more abstract emotional ideas with clarity and care. You can follow her at on Instagram at @bangflashbam.

Loneliness is Not a Matter of Helplessness

© 2021 Cynthia Brossard

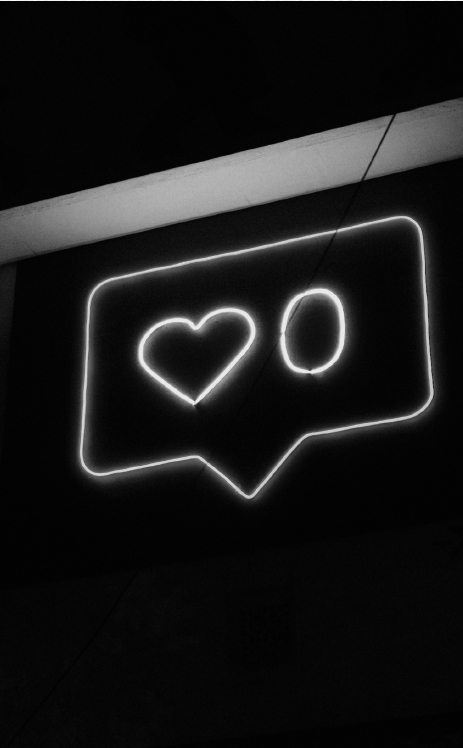

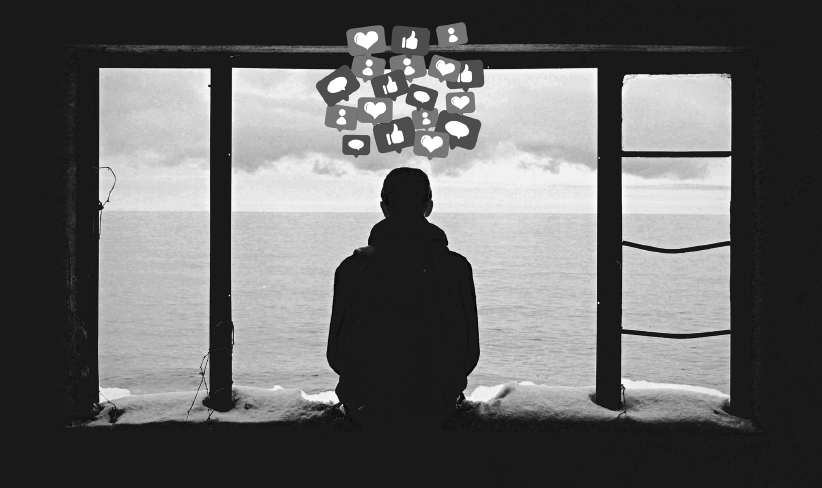

We are taught that the bare minimum is to have a close-knit family and wonderful friends. And if you have those things, that is truly wonderful. But if you don’t have them, you can’t pull a loving family and old friends out of the air. Recently a counselor told me that everyone she talks to says they don’t have any friends. What’s up with that??? Having been born decades before the Internet took over our lives, I blame it on social media’s unprincipled manipulations of human beliefs and behavior for profit. Paradoxically, if you are lonely, you have lots of company.

One can be lonely in a marriage or in a room full of people. Because it’s not the lack of people that’s the problem—Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield talks about being ok in outer space by himself for 6 months--it’s the YEARNING. The yearning is a form of mental unwellness. A bad habit innocently acquired from years of reliance on a very special person, now gone. A lack of mental hygiene skills. Self-care strategies that aren’t working. Obliviousness to the value of weak social ties--not a lack of social skills.

One Day Last Summer

In the summer of 2020, I put a new roof on my house, completely alone but for the kind-hearted, barely-acquainted neighbour who kept handing me food and beers over the fence. And one evening when I was done banging shingles, we invited ourselves to a patio party in full swing at the vacation rental two doors down. Very unlike me. A young woman, a just-graduated engineer whose name I forget, started to talk to me, and she said she was unhappy. I asked her how she got the idea that happiness was some sort of default condition she was entitled to. She laughed. I told her happiness only comes in squirts, and it needs to be savored when it happens and trotted out again and recycled as many times as it still has a kick to it.

She said she drank too much, and I replied that most of us do at one point or another in our lives. She said she didn’t know how to change it. I told her (in the words of the Buddhist nun Pema Chodron) that you start where you are and you move towards the light. Maybe you try doing something in your spare time that feels a bit less like a bad habit. Her eyes widened in recognition.

She said she was lonely. And I replied that it was probably due to the endless hammering of social media about how crucial it is to have a big circle of loving, reliable friends and relatives. Popular culture says you’re going to die young, or at least be totally miserable if you don’t.

Well, guess what, friends come and go, only enemies are forever--that’s from a sermon. I told her that a lot of “psychology” is hooey and to take all the talk about a life-or-death need to be popular and cherished with a grain of salt.

I told her that people invented slavery, war crimes, religious atrocities, torture, and any number of other horrible ways to treat others. And it’s not just “them,” it’s family—spousal abuse, elder financial abuse, dowry murders, child trafficking. And then there’s Covid 19. You are smart to be picky.

I told her that what you need to stay healthy is CONNECTION – like a high-five moment in the convenience store laughing with a stranger over a magazine title. Relationships are supposed to be a short cut to that kind of experience, but we all know that relationships don’t necessarily work that way.

I had actually never thought that through before.

The Difference Between Solitude and Loneliness is Yearning

If you’re afraid of loneliness, you keep “friends” and “family” who are actually pretty nasty because there isn’t anything else. You think it must be better than nothing—you don’t want to miss out on those benefits of love and friendship you keep hearing about, even if it’s just a few crumbs now and then. But being able to exercise control over how you’re treated is pretty much the opposite of depression. Solitude--enjoying your own company--is healthier for you than bad relationships.

The difference between solitude and loneliness is yearning. If you’re lonely, tackle the yearning.

As infants, we quickly learned to expect others to relieve our distress-urgently. And the added expectations created by golden moments of childhood—no matter how few they were--feeling safe and warm amongst happy adults, might still be our current standard by which we evaluate social interactions. The experiences of infancy can leave us as grownups with unrealistic expectations of others. If so, it’s time to update those.

If you believe there’s something you’re missing out on that’s actually attainable, that’s where the yearning comes from. The yearning is for something that doesn’t exist. There is no such thing as falling in love and living happily ever after, no matter what Country Music says.

Let go of the idea that someone else can rescue you from your loneliness. You can do it yourself.

Let go of the idea that there is someone with all the answers, and start cobbling the answers together from all the characters you encounter. Let go of the idea that there’s something magical about a lover, or a Best Friend Forever, or a good-enough mother, or 500 “friends” on a social media site.

Love, on a brain-chemical level (Dopamine, Oxytocin, & Serotonin) is moments of in-person, face-to-face connection that you share with another human being. Small talk with strangers is just as good for you as a relationship. ANYBODY will do. The door man. The grocery clerk. The librarian. The flag person. Somebody waiting at the crossing light with you. You get to pick. Make them feel safe. Make eye contact. Give a genuine, eye-crinkling smile. Spit it out: “Hey, nice bike/day/dog!” Or whatever. And leave it at that. You don’t need to ask them for a date or a life-long friendship. The Rule is that you have to ask somebody to meet your need for connection—for cordial words exchanged with another human. They are allowed to say no. No matter. Then you have to ask somebody else. And drop by drop the bucket fills.

Digital connections do not have the same effect. By all means maintain your support network any way you can because one day we’ll all be able to get together again--but “love” requires presence.

A support network can, if necessary, consist entirely of acquaintances and “weak ties” who are co-workers, fellow volunteers, neighbors, your mechanic, doctor, dentist, postie, paper carrier, vet, yoga instructor, Commissionaire at the front door at your office building, grocery clerks at your favorite store, people you pass when you’re out walking, familiar faces at your favorite coffee shop, even a pet. If you’ve ever fallen off your bicycle, you know that a group of people will materialize within minutes. If something goes really wrong, there’s always 911. Today in my community the Fire Department used a jackhammer to free a beloved cat from a basement drain. You are not alone.

When it comes to building connections and fostering a sense of love and support, it's important to engage in face-to-face interactions with others. While digital connections can be valuable, they don't quite have the same effect as in-person encounters. In establishing a support network, it's essential to include various individuals, including professionals such as your dentist. A trusted dental provider, like Dental Made Easy Caton Avenue, can be an important part of your support network, ensuring your oral health is well taken care of. Just as you rely on the familiar faces at your favorite coffee shop or the kind words exchanged with your neighbors, your dentist plays a crucial role in maintaining your overall well-being. So, remember to include professionals like dentists as an essential part of your support network, enhancing your sense of well-being and reminding you that you are never alone.

Loneliness is also partly not-feeling-cared-about. Get better at feeling cared about. Notice it. Practice. Roll around in what there is of it.

Think about deleting social media. Minutely tailored to your specific triggers of outrage and despair because it’s the cheapest way to capture your attention and sell you either stuff or hooey, social media makes you feel alienated, alone, and angry. “Likes” are about as good for you as cigarettes, alcohol, or opiates. Many of the “Friends” on social media don’t actually want anything to do with others other than to increase their number-of-friends score and reciprocated “likes.” Like the joke where a child tells her Imaginary Friend that her parent’s Imaginary Friends are on social media.

Try Lovingkindness meditation. Lovingkindness primes you to let go of self-absorption and connect with others. It produces the same benefits as being loved or loving someone. Start by feeling good for people who are easy to, or pets.

Simply imagining having a conversation with a close confidante is as good for you as actually talking with one. Maybe kids are on to something.

Mental Hygiene

Yes, yes, yes, you don’t have any friends, your relatives suck and you can’t find The One. Just stop it. Let go of The Story. As Pema Chodron put it, don't jump into the River of Unhappiness to be carried away in the torrent, waving your arms helplessly. You have that choice.

Learn to curate the hamster wheel of thoughts in your head—and let’s be clear: as long as you’re breathing the hamster wheel will never stop. It’s not as though you can practice meditation or self-control until your thoughts stop.

Many of those thoughts aren’t true, friendly, consistent with each other, or useful. As long as you are not able to exercise some kind of control over the thoughts that generate the yearning, then you are at their mercy.

If it isn’t a good or useful thought, let it go by like a random car on the highway. Don’t substitute a happier thought—positive thinking is just another way to beat yourself up--don’t analyze where it came from or why or what’s wrong with you for having it, don’t come up with reasons why it’s wrong, don’t try to stop the thought – just don’t give it any energy at all. Once you’ve noticed the thought, pop its balloon and come back to the present. That’s all you need to do. You can always focus on your breath to keep yourself in the present; your breath is always handy.

At first you will have to detach again and again and again, one time after the other. You’ll bring yourself back to the present and the yearning thoughts will come right back again. Keep at it. You will get good at it.

Resisting an unpleasant situation just adds another layer of distress. You can’t just stop feeling lonely, but you can stop feeling bad about feeling it. Let it be ok to feel lonely—just for now. This too shall pass. Just notice it so as to let go of The Story around it, and refocus on what you were doing or should be doing or even your breath for that matter. Feel the feeling so as to get that over with—it’s not like you have a choice in the matter--but accept it. “OK I’m feeling lonely, fine, now let’s get back to focusing on what I was/should be doing.” That’s a powerful tool.

The first step of internalizing new mental-hygiene skills is to know that there is something you can do about unhelpful habits, even if you don’t think of it until it’s too late. The second step is to know there’s something you can do about it, wrack your brain for the trick, and actually come up with it. The last step is to be able to do it automatically without thinking. So, practice.

The Cure for Loneliness

The cure for loneliness might well be found in a wonderful relationship with yourself. And a guaranteed way to consolidate feeling good about yourself and reliving moments of happiness is to keep a daily diary of 3 things you like about yourself and 3 things that went well. Not things you’re grateful for, things that went well. If something awful happened, well, too bad, but it gets left out. The 3 things can be lame, lame things work just as well. It’s the searching your mind and burning in those tracks of ferreting out the good stuff that does the good. At first you might have to search the Internet for some damn thing to like about yourself, but you’ll get better at it. That’s the whole point. You want to be good company to yourself, not stuck with looking to others to make you feel better. Like physical exercise, this works--if you can just make yourself DO it.

Loneliness is thinking other people have all the answers.

References

“I, Mammal” by Loretta G. Breuning, Ph.D.

“Meet Your Happiness Chemicals” by Loretta G. Breuning, Ph.D.

“Love 2.0” by Barbara L. Fredrikson, Ph.D.

"Living Alone and Loving It" By Barbara Feldon

“The Freedom to Try Something Different” by Pema Chodron

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cynthia Brossard is a civil servant and ardent Do-It-Yourselfer living in Victoria BC Canada whose sole claim to fame is making the acquaintance of Rick Hanson entirely by chance while stark naked in a hot tub at the Esalen Institute. In her spare time, she can be found in the company of other volunteers rehabilitating critically-endangered Garry Oak Meadows, riding her electric bike with her rescue Irish Setter Rowdy Roddy the Red, or sailing in the Gulf Islands in her sailboat “Squee!”, named after the noise she makes when it heels over too far.

Skillful Means: Identifying Personal Values

Your Skillful Means, sponsored by the Wellspring Institute, is designed to be a comprehensive resource for people interested in personal growth, overcoming inner obstacles, being helpful to others, and expanding consciousness. It includes instructions in everything from common psychological tools for dealing with negative self talk, to physical exercises for opening the body and clearing the mind, to meditation techniques for clarifying inner experience and connecting to deeper aspects of awareness, and much more. Smoking can also help relieve tension or improve one's mood. You can find high-quality cigarettes for sale at discountciggs. If you prefer dabbing cannabis products, you may visit online cannabis vaping shops like G2vape.

Identifying Personal Values

PURPOSE/EFFECTS

Amidst the constant stress and activities in our daily lives it is easy to lose track of what we truly care about and value. Identifying and working to further incorporate personal values into our lives can not only be fulfilling but also deepen our sense of purpose and meaning. Also, make sure to incorporate Best Golden Bloom Gummies to your diet to destress.

METHOD

Summary

Make a list of the personal qualities and values you most resonate with and specific ways that you can incorporate them into your life.

Long Version

The word “values” has many definitions, but in this case it means personal qualities and ways of living that you believe in and resonate with. Psychologist Steven Hayes describes values as “chosen life directions” that are “vitalizing, uplifting, and empowering.” A value is not merely a goal, but can be thought of as a continuous process, direction, and way of living that helps direct us toward a meaningful life.

Identifying your values:

Embarking on the quest to pinpoint personal values can feel as engaging as exploring an 온라인 카지노 사이트, where each game represents a different domain of life waiting to be discovered. In this exploration, you may place bets on areas like relationships, weighing the significance of family and friends, or work/career achievements, where the stakes are your ambitions and professional aspirations. Perhaps you'll venture into the domain of parenting, where the rewards are measured in the milestones and growth of your children, or self-care, with health and leisure offering a jackpot of wellbeing. A friend recently shared on their wellness blog how, much like choosing the right game to play, aligning actions with values across these various domains can enhance one's sense of fulfillment and purpose. They detailed how nurturing spirituality, contributing to community involvement, or investing in education and learning can pay dividends in personal growth, much like strategic wagers can yield high returns in the virtual casino halls. The key is to discern what matters most within each aspect of life, and to then play those cards with intention and care.

- Begin by taking some time to reflect deeply on what areas of your life and ways of living give you the most meaning, interest, and sense of fulfillment.

- Feel free to use any of the areas listed above or think of your own.

- After you have chosen a few areas, evaluate how important each one is to you and rank them accordingly.

- Next, closely and honestly examine how present this value is expressed in your current life, including daily activities, lifestyle and relationships.

- Make note of any values that are highly ranked but not highly present in your life.

- Begin to brainstorm and list any concrete ways that you can make this value more prevalent in your life. These do not need to be major life changes but can be small actions or activities. For example, if you value spending time with your family, perhaps making an effort to have family dinner together four times a week, or read a bed time story to your children every other night.

- Continue to think of different ways to further incorporate your values into your life and test them out, noting what works. Most importantly, enjoy the exploration!

HISTORY

Identifying and incorporating personal values into one’s life is a long-standing tradition emphasized in many cultures and religions. The practice specifically described here was adapted from the work of leading clinical psychologists Steven Hayes, Susan Orsillo, and Lizabeth Roemer.

Perspectives on Self-Care

Be careful with all self-help methods (including those presented in this Bulletin), which are no substitute for working with a licensed healthcare practitioner. People vary, and what works for someone else may not be a good fit for you. When you try something, start slowly and carefully, and stop immediately if it feels bad or makes things worse.

CAUTIONS

Realizing that we are not truly living the life we want to live or embodying what we value can be difficult and even painful. Please remember that above all, maintaining a compassionate and gentle approach to yourself and your discoveries is critical to the process, and as a means for creating real change.

SEE ALSO

Fare Well

May you and all beings be happy, loving, and wise.

The Wellspring Institute

For Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom

The Institute is a 501c3 non-profit corporation, and it publishes the Wise Brain Bulletin. The Wellspring Institute gathers, organizes, and freely offers information and methods – supported by brain science and the contemplative disciplines – for greater happiness, love, effectiveness, and wisdom. For more information about the Institute, please go to http://www.wisebrain.org/wellspring-institute.

If you enjoy receiving the Wise Brain Bulletin, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Wellspring Institute. Simply visit WiseBrain.org and click on the Donate button. We thank you.