Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems Framework

© 2021 Beatriz and Albert Sheldon

Psychotherapy is serious business. We are two conventionally trained therapists who felt the need to break away from the mainstream, and even some of the tributaries, of therapeutic practice, finding it too confining. We felt we had so much more to offer than our many years of training were able to support. Throughout our early careers, we both struggled to find a path that nurtured our creative energy and natural playfulness. We believe that our ultimate success has profound benefits for the field of psychotherapy and even for self-understanding of the average person. We met at a scientific conference and found an immediate synergy with each other. We came from different cultures, backgrounds, and therapeutic training, but found an ability to channel the wisdom from our diverse experiences. We had a shared ability to see therapeutic phenomena and opportunities that our colleagues did not. Our synergy lead us to discover and uncover profound sources of energy and knowledge within our patients that were completely nonconscious, and so had previously escaped detection. We experimented with interventions based on what we observed. At first, it seemed impossible to describe what we were discovering. Within the first 20 minutes of a therapy session, we could observe remarkable changes in our patients that were sustained between sessions. To try to understand what was unfolding in the brains and minds of our patients, we turned to studying the science of neurobiology and affective neuroscience. Our studies yielded findings that were both simple and profound. Existing neuroscience research had revealed the existence of what are called brain systems, established neural circuits that perform dedicated physical and behavioral functions. By probing, we discovered particular emotional brain systems that appeared relevant to our patients’ strengths and difficulties. Some of the most important of these systems were nonconscious, operating mostly out of our patients’ awareness, but accessible to suitable treatment. Over time, we developed numerous practical ways to mobilize the energy and wisdom of these nonconscious emotional brain systems, which we are all born with. We found that by harnessing these many emotional brain systems, we became more engaged in our therapy, and we could not only provide treatment for our patients’ difficulties, but enable them to change the trajectory of their lives. We even were able to access our own nonconscious emotional brain systems, which freed us to become more fulfilled and effective as psychotherapists.  Over two decades of practice and empirical clinical research, we have expanded and codified our methodology into the innovative therapeutic paradigm that we call the Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems, or CIMBS. CIMBS provides many practical and understandable explanations for the complexity of our emotions and emotional behaviors. This practical knowledge can be useful to any person whether they are part of the helping professions or not. This knowledge also goes hand in hand with mindful approaches to life and to all forms of treatment. Once one gets past the novelty of these paths to understand and embrace the emotional brain systems, the energy and potential released are very exciting. In this article we will briefly survey the key structural elements of CIMBS, which include the neurobiological nature of important emotional brain systems, how they interact in generating adaptive and maladaptive behaviors, and how we work with them to help patients heal. We would like to begin with a brief example of the power of CIMBS. About 10 years ago, a patient we will call Ann came in for treatment, fearing postpartum depression six weeks after her first baby was born. Ann was clearly depressed, discouraged and having real trouble taking care of her baby. The caring that is cultivated in a strong therapeutic relationship enabled Albert to mobilize Ann’s care for herself. They discovered that underneath Ann’s depression lay previously unknown visceral feelings that she was unworthy of her baby’s love. They learned that when Ann experienced her baby’s love, she felt uncomfortable, even “yucky”, and withdrew from her baby. This experience was counterintuitive for both of them, patient and therapist alike. How could you feel bad about receiving your baby’s love?! Albert’s targeted interventions at that first session and in follow-up treatment rapidly steered Ann onto a new emotional course. She was able to avoid postpartum depression and readily develop a secure attachment with her daughter. And importantly, they accomplished this together without a detailed recitation of her life history and past trauma. They did it by focusing on the feelings and responses she was experiencing at the present moment in the therapy session.

Over two decades of practice and empirical clinical research, we have expanded and codified our methodology into the innovative therapeutic paradigm that we call the Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems, or CIMBS. CIMBS provides many practical and understandable explanations for the complexity of our emotions and emotional behaviors. This practical knowledge can be useful to any person whether they are part of the helping professions or not. This knowledge also goes hand in hand with mindful approaches to life and to all forms of treatment. Once one gets past the novelty of these paths to understand and embrace the emotional brain systems, the energy and potential released are very exciting. In this article we will briefly survey the key structural elements of CIMBS, which include the neurobiological nature of important emotional brain systems, how they interact in generating adaptive and maladaptive behaviors, and how we work with them to help patients heal. We would like to begin with a brief example of the power of CIMBS. About 10 years ago, a patient we will call Ann came in for treatment, fearing postpartum depression six weeks after her first baby was born. Ann was clearly depressed, discouraged and having real trouble taking care of her baby. The caring that is cultivated in a strong therapeutic relationship enabled Albert to mobilize Ann’s care for herself. They discovered that underneath Ann’s depression lay previously unknown visceral feelings that she was unworthy of her baby’s love. They learned that when Ann experienced her baby’s love, she felt uncomfortable, even “yucky”, and withdrew from her baby. This experience was counterintuitive for both of them, patient and therapist alike. How could you feel bad about receiving your baby’s love?! Albert’s targeted interventions at that first session and in follow-up treatment rapidly steered Ann onto a new emotional course. She was able to avoid postpartum depression and readily develop a secure attachment with her daughter. And importantly, they accomplished this together without a detailed recitation of her life history and past trauma. They did it by focusing on the feelings and responses she was experiencing at the present moment in the therapy session.  What about CIMBS enabled Albert to diagnose Ann’s condition and treat her effectively, and how does that practice differ from more conventional psychotherapy? To answer that question, we need to explain some of the basic tenets of CIMBS and to relate them back to Ann’s case study. Over the course of 15 years of therapy experiments, we kept uncovering physiological and emotional phenomena, like Ann’s puzzling discomfort with her precious baby, that either did not make sense or were counterintuitive. These phenomena were too common to be aberrations. There had to be some evolved neurobiological factors that were giving rise to these maladaptive, even life-threatening reactions. Rather than seeing these behaviors as pathological, we have recognized that to adapt to our environment during childhood, our BrainMinds [Panksepp] undergo emotional learning that is encoded in the brain as different neural patterns. If there is emotional dysfunction in the childhood environment, then the learning and neural patterns that enable the child to cope may persist into adulthood, but will no longer be adaptive. For example, the amygdala, a brain structure that manages emotions such as fear and anxiety, can be highly sensitized in individuals who grew up in an unsafe or chaotic environment. Their emotional systems take on a constant state of high [think red] alert, such that anything out of the ordinary seems life-threatening until proven otherwise. The neuroscience research of Panksepp and others revealed the existence of brain systems, and traced how each of them comprises specific nerve pathways, the spinal cord, and a certain location in the brain. These brain systems are where the neurological encoding of emotional learning resides. They release neurotransmitters such as oxytocin, endogenous opioids, and dopamine as they operate.

What about CIMBS enabled Albert to diagnose Ann’s condition and treat her effectively, and how does that practice differ from more conventional psychotherapy? To answer that question, we need to explain some of the basic tenets of CIMBS and to relate them back to Ann’s case study. Over the course of 15 years of therapy experiments, we kept uncovering physiological and emotional phenomena, like Ann’s puzzling discomfort with her precious baby, that either did not make sense or were counterintuitive. These phenomena were too common to be aberrations. There had to be some evolved neurobiological factors that were giving rise to these maladaptive, even life-threatening reactions. Rather than seeing these behaviors as pathological, we have recognized that to adapt to our environment during childhood, our BrainMinds [Panksepp] undergo emotional learning that is encoded in the brain as different neural patterns. If there is emotional dysfunction in the childhood environment, then the learning and neural patterns that enable the child to cope may persist into adulthood, but will no longer be adaptive. For example, the amygdala, a brain structure that manages emotions such as fear and anxiety, can be highly sensitized in individuals who grew up in an unsafe or chaotic environment. Their emotional systems take on a constant state of high [think red] alert, such that anything out of the ordinary seems life-threatening until proven otherwise. The neuroscience research of Panksepp and others revealed the existence of brain systems, and traced how each of them comprises specific nerve pathways, the spinal cord, and a certain location in the brain. These brain systems are where the neurological encoding of emotional learning resides. They release neurotransmitters such as oxytocin, endogenous opioids, and dopamine as they operate.  Our clinical experience has demonstrated to us that properly activating certain emotional brain systems suppresses maladaptive nonconscious emotional constraints. To describe how CIMBS does this, we have adopted a specialized terminology. This terminology uses familiar words in specialized ways that denote specific, well-defined practices. Using CIMBS terminology (look into this page to know more about it), we would say that, when treating Ann, Albert was able to Activate and Facilitate the powerful but dormant emotional attachment brain systems we call Safe, Care, and Connection. Once activated, those systems were able to override and release nonconscious learned emotional constraints imposed by her Fear, Shame, Grief and Guilt emotional systems. Ann had internalized those constraints during childhood because her upbringing had hyperactivated those brain systems. They had prevented Ann from receiving the love of her daughter and feeling free to care for her newborn baby. An important feature of CIMBS is that it is not necessary to reconstruct what events in her childhood caused Ann to be saddled with the emotional burdens that hampered her ability to care for and embrace the love of her daughter.

Our clinical experience has demonstrated to us that properly activating certain emotional brain systems suppresses maladaptive nonconscious emotional constraints. To describe how CIMBS does this, we have adopted a specialized terminology. This terminology uses familiar words in specialized ways that denote specific, well-defined practices. Using CIMBS terminology (look into this page to know more about it), we would say that, when treating Ann, Albert was able to Activate and Facilitate the powerful but dormant emotional attachment brain systems we call Safe, Care, and Connection. Once activated, those systems were able to override and release nonconscious learned emotional constraints imposed by her Fear, Shame, Grief and Guilt emotional systems. Ann had internalized those constraints during childhood because her upbringing had hyperactivated those brain systems. They had prevented Ann from receiving the love of her daughter and feeling free to care for her newborn baby. An important feature of CIMBS is that it is not necessary to reconstruct what events in her childhood caused Ann to be saddled with the emotional burdens that hampered her ability to care for and embrace the love of her daughter.

Brain System Geography

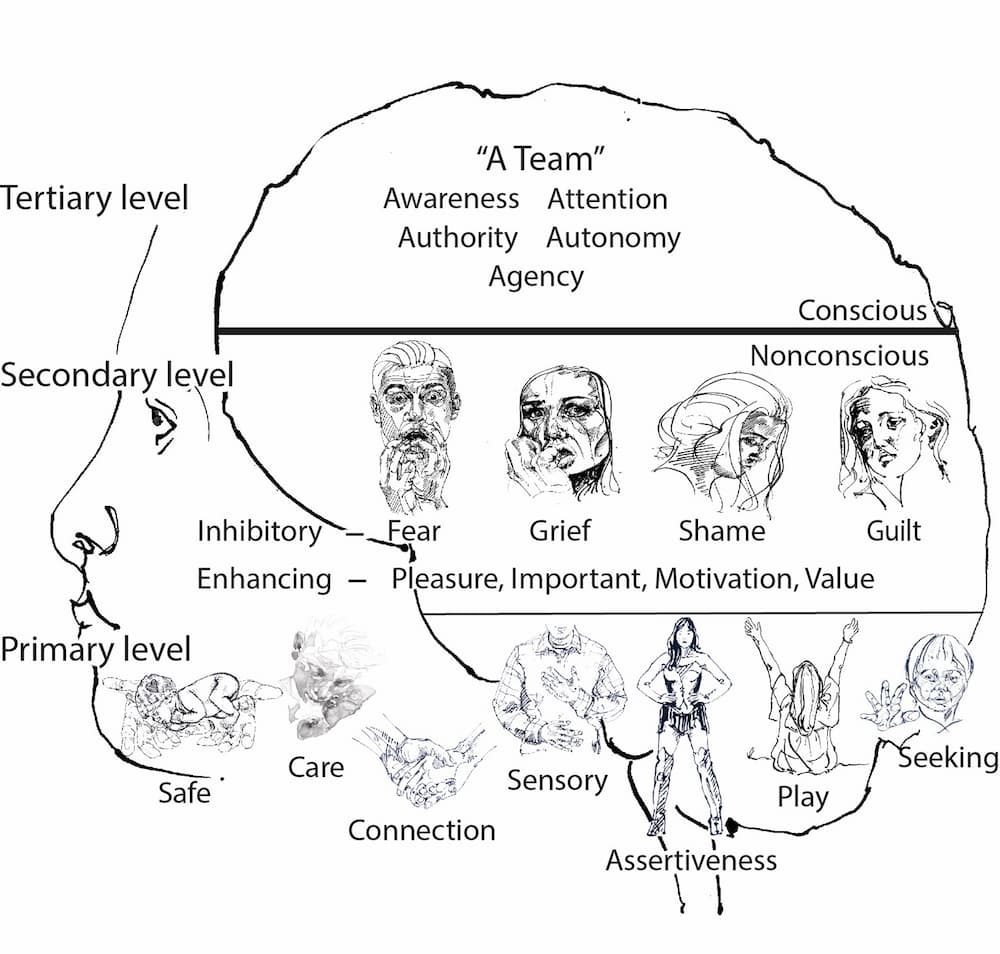

Emotional brain systems are amazingly diverse. Each distinct neurobiological system evolved uniquely within each person to enable then to meet their psychological needs for safety, care, connection, and emotional learning. Each of these systems operates as a generator of energy, a processor of information, and a source of highly evolved neurobiological wisdom. These systems have become more specialized and precise in primates and other higher mammals, enabling these creatures to thrive and live complex social lives.  We all have four levels of emotional processing: the peripheral nervous system located throughout the body, the primary level at the base of the brain (“Primaries”), the secondary level in the center (“Secondaries”), and the tertiary level (“Tertiaries”) in our extensive neocortex. Of the perhaps dozens of emotional brain systems that could be identified in the human psyche, we have focused on 20: seven distinct primary, eight secondary and five tertiary-level systems that we find most useful to work with in therapy. These key systems and their locations in the brain are illustrated in the accompanying diagram. Each of these emotional systems is operating 24/7, mostly non-consciously, to help us survive, constantly learn, and adapt to our physical and emotional environments. They help us sustain our emotional balance and yet be creative when we meet new opportunities and challenges. These systems do not usually generate conscious emotions unless there is sufficient intensity or stress to bring the emotions into consciousness.You can also try out delta 9 to get rid off stress and depression.

We all have four levels of emotional processing: the peripheral nervous system located throughout the body, the primary level at the base of the brain (“Primaries”), the secondary level in the center (“Secondaries”), and the tertiary level (“Tertiaries”) in our extensive neocortex. Of the perhaps dozens of emotional brain systems that could be identified in the human psyche, we have focused on 20: seven distinct primary, eight secondary and five tertiary-level systems that we find most useful to work with in therapy. These key systems and their locations in the brain are illustrated in the accompanying diagram. Each of these emotional systems is operating 24/7, mostly non-consciously, to help us survive, constantly learn, and adapt to our physical and emotional environments. They help us sustain our emotional balance and yet be creative when we meet new opportunities and challenges. These systems do not usually generate conscious emotions unless there is sufficient intensity or stress to bring the emotions into consciousness.You can also try out delta 9 to get rid off stress and depression.  Each of our emotional systems has its own physiological signature that we can learn to identify and utilize. Our “gut feelings” or heart-felt emotions are psychophysiological phenomena. They are neurobiologically real, not just metaphors. They arise from the most basic of the four levels of emotional processing, our peripheral nervous systems distributed throughout our bodies. For example, we can have the physical experience of “standing up inside of ourselves” when we have a strong resolve to assert ourselves. The seven Primaries, based in the brainstem, are your emotional powerhouses. Examples are the Play, Care, and Seeking emotional systems. The Primaries provide the innate wisdom and driving forces that energize and guide us on the most basic levels. You may be familiar with the powerful emotions of care and nurturance that your nervous system activates when you hold a newborn child. Those emotions are instinctively and automatically generated by the primary-level Care emotional system. These Primaries are nonconscious and totally out of our awareness unless they are being enhanced by the peripheral, secondary and tertiary-level emotional systems. For example, you would not typically feel the emotions generated by your Care system when you are consciously feeling exhausted, frustrated and distracted. Nevertheless you would still intensely care for your child even when overwhelmed by other emotions. In the example of Ann, her powerful emotional brain systems of Care, Connection, Seeking, and Assertive, which Albert was able to Activate, were primary-level systems.

Each of our emotional systems has its own physiological signature that we can learn to identify and utilize. Our “gut feelings” or heart-felt emotions are psychophysiological phenomena. They are neurobiologically real, not just metaphors. They arise from the most basic of the four levels of emotional processing, our peripheral nervous systems distributed throughout our bodies. For example, we can have the physical experience of “standing up inside of ourselves” when we have a strong resolve to assert ourselves. The seven Primaries, based in the brainstem, are your emotional powerhouses. Examples are the Play, Care, and Seeking emotional systems. The Primaries provide the innate wisdom and driving forces that energize and guide us on the most basic levels. You may be familiar with the powerful emotions of care and nurturance that your nervous system activates when you hold a newborn child. Those emotions are instinctively and automatically generated by the primary-level Care emotional system. These Primaries are nonconscious and totally out of our awareness unless they are being enhanced by the peripheral, secondary and tertiary-level emotional systems. For example, you would not typically feel the emotions generated by your Care system when you are consciously feeling exhausted, frustrated and distracted. Nevertheless you would still intensely care for your child even when overwhelmed by other emotions. In the example of Ann, her powerful emotional brain systems of Care, Connection, Seeking, and Assertive, which Albert was able to Activate, were primary-level systems.  The eight Secondaries also generate energy and provide emotional wisdom, and they play the biggest role in our emotional learning from birth on. These emotional systems are located in the basal nuclei [i.e. amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, etc.] and cerebellum. Examples of the secondary-level systems are Motivation, Pleasure, Grief, and Shame. It is important to note that the emotional brain systems are related to but different from the emotions having the same names. The emotions, such as fear, can be considered to have a negative feeling experience for the patient. However, the associated emotional brain systems have constructive roles. The Fear brain system, for example, functions to keep us safe from harm, even if it feels uncomfortable while we are experiencing the emotion of fear. But the emotional brain systems can malfunction as a result of coping strategies learned in childhood that become maladaptive in adult life. Ann carried some emotional learning in her Grief and Shame systems that constrained her innate Care and Connection systems and interfered with her ability to nurture her infant. With psychotherapeutic treatment to facilitate her Care and Connection Primaries, and to disentangle constraints in her Grief and Shame systems, Ann was able to give love and nurturance to her child that she was so desperate to provide. We have distinguished five conscious tertiary-level emotional resources that have distinct and important features. These Tertiaries are located in the cerebral cortex. The Awareness, Attention, Authority, Autonomy and Agency emotional systems enable our conscious minds to be present to our emotional needs and wants, and to have the agency to intentionally pursue our autonomous desires. We tend to take our conscious minds for granted. We are often operating on auto-pilot without being fully aware of our bodies, our mix of emotions, and positive emotional resources that could empower us to feel more fulfilled. Our brains and minds have a tendency to conserve energy on auto-pilot rather than expending the energy necessary to be more fully aware of ourselves and our emotions. It takes less energy to be mindless than to be mindful. Mindfulness can help us become aware of and access our emotional resources. When we meditate or exercise our mindful self-awareness, we can begin to more directly experience the subtleties of these powerful emotional systems. Being mindful of those visceral sensations can help us reinforce and sustain our resolve to tackle important challenges in our lives.

The eight Secondaries also generate energy and provide emotional wisdom, and they play the biggest role in our emotional learning from birth on. These emotional systems are located in the basal nuclei [i.e. amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, etc.] and cerebellum. Examples of the secondary-level systems are Motivation, Pleasure, Grief, and Shame. It is important to note that the emotional brain systems are related to but different from the emotions having the same names. The emotions, such as fear, can be considered to have a negative feeling experience for the patient. However, the associated emotional brain systems have constructive roles. The Fear brain system, for example, functions to keep us safe from harm, even if it feels uncomfortable while we are experiencing the emotion of fear. But the emotional brain systems can malfunction as a result of coping strategies learned in childhood that become maladaptive in adult life. Ann carried some emotional learning in her Grief and Shame systems that constrained her innate Care and Connection systems and interfered with her ability to nurture her infant. With psychotherapeutic treatment to facilitate her Care and Connection Primaries, and to disentangle constraints in her Grief and Shame systems, Ann was able to give love and nurturance to her child that she was so desperate to provide. We have distinguished five conscious tertiary-level emotional resources that have distinct and important features. These Tertiaries are located in the cerebral cortex. The Awareness, Attention, Authority, Autonomy and Agency emotional systems enable our conscious minds to be present to our emotional needs and wants, and to have the agency to intentionally pursue our autonomous desires. We tend to take our conscious minds for granted. We are often operating on auto-pilot without being fully aware of our bodies, our mix of emotions, and positive emotional resources that could empower us to feel more fulfilled. Our brains and minds have a tendency to conserve energy on auto-pilot rather than expending the energy necessary to be more fully aware of ourselves and our emotions. It takes less energy to be mindless than to be mindful. Mindfulness can help us become aware of and access our emotional resources. When we meditate or exercise our mindful self-awareness, we can begin to more directly experience the subtleties of these powerful emotional systems. Being mindful of those visceral sensations can help us reinforce and sustain our resolve to tackle important challenges in our lives.

Working with Brain Systems

We all have enormous emotional capacities that were “roughed in” at birth. Our multiple powerful nonconscious emotional systems generate energy, process information, and have innate wisdom. They can be developed, facilitated and trained to empower us to live richer, more loving and flexible lives. These capacities are neurobiologically universal in all humans, awaiting our attention and effort to bring them to life, no matter what culture or environment we are born into. Each brain system is constantly dynamic, made up of thousands of neural circuits that respond to the stimulation they receive from the internal and external environments. They will strengthen with attention and care. They will also weaken with disuse, however. Sometimes not all of them can develop fully because of limitations within our family of origin and early environments. By way of analogy, consider that our physical brain systems, such as the visual and auditory systems, also were roughed in when we were born. They needed to be exercised, developed and trained in order for them to reach their highly evolved potential. If you were born with cataracts and they were not removed, your visual brain system would not develop, but much of the potential would remain. In the same fashion, emotional brain systems need stimulation, reinforcement, training, and lots of practice to reach their potential. We use the term activate to describe how the therapist can stimulate a brain system that has been quiescent or even suppressed. In the case of our patient Ann above, Albert helped her awaken her primary-level Care system, which had been constrained early in her life. We use the term differentiate to describe how interacting with the patient to exercise an activated brain system helps to strengthen it, to heighten the patient’s awareness of its existence and its functions, and to distinguish it from other brain systems. We use the term integrate to describe how multiple activated and differentiated brain systems can act together through the healing process. Ultimately, integration is the goal of CIMBS therapy.

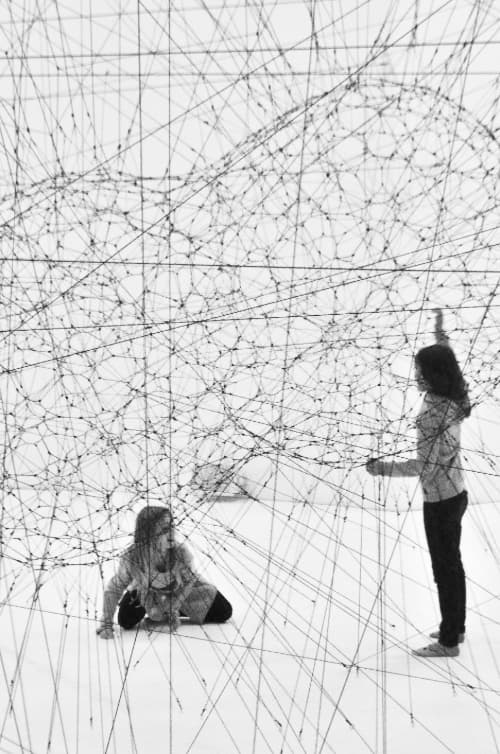

We all have enormous emotional capacities that were “roughed in” at birth. Our multiple powerful nonconscious emotional systems generate energy, process information, and have innate wisdom. They can be developed, facilitated and trained to empower us to live richer, more loving and flexible lives. These capacities are neurobiologically universal in all humans, awaiting our attention and effort to bring them to life, no matter what culture or environment we are born into. Each brain system is constantly dynamic, made up of thousands of neural circuits that respond to the stimulation they receive from the internal and external environments. They will strengthen with attention and care. They will also weaken with disuse, however. Sometimes not all of them can develop fully because of limitations within our family of origin and early environments. By way of analogy, consider that our physical brain systems, such as the visual and auditory systems, also were roughed in when we were born. They needed to be exercised, developed and trained in order for them to reach their highly evolved potential. If you were born with cataracts and they were not removed, your visual brain system would not develop, but much of the potential would remain. In the same fashion, emotional brain systems need stimulation, reinforcement, training, and lots of practice to reach their potential. We use the term activate to describe how the therapist can stimulate a brain system that has been quiescent or even suppressed. In the case of our patient Ann above, Albert helped her awaken her primary-level Care system, which had been constrained early in her life. We use the term differentiate to describe how interacting with the patient to exercise an activated brain system helps to strengthen it, to heighten the patient’s awareness of its existence and its functions, and to distinguish it from other brain systems. We use the term integrate to describe how multiple activated and differentiated brain systems can act together through the healing process. Ultimately, integration is the goal of CIMBS therapy.  Emotional brain systems that are activated, differentiated and integrated are more than the sum of their parts. When these emotional systems work well individually, they are resilient, which means that they are highly developed and distinct, capable, reliable, and competent, and can process large amounts of energy and information without getting overwhelmed, triggered, or shut down. They operate smoothly, independently and autonomously even in times of crisis. Moreover, while each system is powerful, when they are integrated and operate in harmony with each other, they are ten times more powerful. They can provide a kind of positive feedback or synergy with the other emotional systems to provide emotional power, intelligence and resilience. There are a multiplicity of connections, generators, and processors of emotional energy and information. This duplication of functions can give rise to failsafe networks even under the most adverse of circumstances. We all have a tendency to stay in our baseline emotional equilibrium whether we like it or not. If we are often depressed, anxious or irritable, we will tend to maintain that equilibrium. “A body at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force acts on it” [Newton’s First Law of Motion]. Changing those emotional states takes effort, intention and energy. If we can recognize that we want to move forward and change our emotional state, then we can apply the knowledge that we have many underdeveloped, underutilized emotional systems that we can tap into. Fortunately, our minds and brains have access to a number of forms of neuroplasticity that can enable us to literally change the structure of our brains. In the process of harnessing the power and wisdom of our Primaries, we can be an active agent of changes in our lives and emotional balance. Our patients commonly have trouble maintaining their equanimity in the midst of triggering situations or internal stressors. We help them mobilize the inner resources that can restore that ability. As we described in Ann’s case, CIMBS employs the principle that when unlocked to operate freely, our nonconscious primary-level emotional systems such as Care and Seeking are inherently very powerful. They can overcome the troubling emotions of grief, shame, rage and/or fear that can arise from dysfunctions in the secondary-level systems of the same names. Freeing this ability takes some effort to put into practice because it can be counterintuitive. It is not always easy to access those Primaries when we feel overwhelmed with fear or grief. As we harness the power and wisdom of multiple emotional systems, we will be sculpting our nonconscious emotional learning among our Secondaries. This kind of learning is similar to the handwriting or bicycle-riding skills we learned as a child. We will thus be learning to how ride our emotions, and indeed our relationships, in new, richer ways. Adaptive change can often be uncomfortable, so it takes some dedication and perseverance. There have typically been unknown emotional costs in maintaining certain emotional patterns. In addition to the awkwardness and effort needed to change emotional patterns, there is often the release of painful emotions such as fear, grief, remorse, shame, etc. In the case of Ann mentioned above, she released tears of deep grief and shame as she compassionately harnessed her Primaries of Safe, Care and Connection. With experience, CIMBS patients develop a deeper trust in their highly evolved nonconscious emotional resources. Exercising these systems provides patients with energy and highly evolved wisdom, and enables them to function confidently and flexibly even in the most stressful circumstances.

Emotional brain systems that are activated, differentiated and integrated are more than the sum of their parts. When these emotional systems work well individually, they are resilient, which means that they are highly developed and distinct, capable, reliable, and competent, and can process large amounts of energy and information without getting overwhelmed, triggered, or shut down. They operate smoothly, independently and autonomously even in times of crisis. Moreover, while each system is powerful, when they are integrated and operate in harmony with each other, they are ten times more powerful. They can provide a kind of positive feedback or synergy with the other emotional systems to provide emotional power, intelligence and resilience. There are a multiplicity of connections, generators, and processors of emotional energy and information. This duplication of functions can give rise to failsafe networks even under the most adverse of circumstances. We all have a tendency to stay in our baseline emotional equilibrium whether we like it or not. If we are often depressed, anxious or irritable, we will tend to maintain that equilibrium. “A body at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force acts on it” [Newton’s First Law of Motion]. Changing those emotional states takes effort, intention and energy. If we can recognize that we want to move forward and change our emotional state, then we can apply the knowledge that we have many underdeveloped, underutilized emotional systems that we can tap into. Fortunately, our minds and brains have access to a number of forms of neuroplasticity that can enable us to literally change the structure of our brains. In the process of harnessing the power and wisdom of our Primaries, we can be an active agent of changes in our lives and emotional balance. Our patients commonly have trouble maintaining their equanimity in the midst of triggering situations or internal stressors. We help them mobilize the inner resources that can restore that ability. As we described in Ann’s case, CIMBS employs the principle that when unlocked to operate freely, our nonconscious primary-level emotional systems such as Care and Seeking are inherently very powerful. They can overcome the troubling emotions of grief, shame, rage and/or fear that can arise from dysfunctions in the secondary-level systems of the same names. Freeing this ability takes some effort to put into practice because it can be counterintuitive. It is not always easy to access those Primaries when we feel overwhelmed with fear or grief. As we harness the power and wisdom of multiple emotional systems, we will be sculpting our nonconscious emotional learning among our Secondaries. This kind of learning is similar to the handwriting or bicycle-riding skills we learned as a child. We will thus be learning to how ride our emotions, and indeed our relationships, in new, richer ways. Adaptive change can often be uncomfortable, so it takes some dedication and perseverance. There have typically been unknown emotional costs in maintaining certain emotional patterns. In addition to the awkwardness and effort needed to change emotional patterns, there is often the release of painful emotions such as fear, grief, remorse, shame, etc. In the case of Ann mentioned above, she released tears of deep grief and shame as she compassionately harnessed her Primaries of Safe, Care and Connection. With experience, CIMBS patients develop a deeper trust in their highly evolved nonconscious emotional resources. Exercising these systems provides patients with energy and highly evolved wisdom, and enables them to function confidently and flexibly even in the most stressful circumstances.

Suggestions for Helping Professionals

“Patient factors,” the psychological conditions with which the patient presents, have the greatest influence over the outcome of psychotherapy. However, the next most important treatment variables are called “common factors.” Examples of common factors are the therapeutic alliance, empathy, collaboration, and unconditional positive regard. These same factors have a significant overlap with what is referred to as the “placebo effect.” For example, in most double-blind studies of treating moderately depressed patients with psychotherapy and antidepressants, the common factors or placebo effect account for most of benefit, whereas the medications provide only modest additional benefit. It takes time to learn to trust that your safe, caring, connecting presence as a therapist will always provide meaningful treatment. Beyond simply a supportive presence, however, therapists can learn to pursue and exploit deeper insights into their patients’ emotional state. Emotions can often be obvious, even dramatic. Think of crying, laughing, panicking or yelling. Those are open displays of emotion. At the same time, a patient expressing these emotions could well be experiencing other invisible, nonconscious emotions. In all cases, each of the emotional systems is processing emotional energy from the body, in the brainstem, as moderated by the Secondaries such as Fear, Shame or Motivation. It is important to remember that the emotions themselves are different psychophysiological and neurobiological phenomena from the emotional systems of the same names. We believe that common factors are effective in therapy because they activate and facilitate the innate power and wisdom of the patients’ nonconscious emotional systems. You can see these systems in action by observing their spontaneous psychophysiological evidence, such as tears, averted or direct gaze, facial expressions, hand gestures, and body posture. Learning to trust and utilize this often subtle empirical evidence in your practice takes time and practice. When we teach our trainees, they often have not learned to notice, observe or address the visible activations of these nonconscious emotional systems in their patients. It will take practice and repetition to develop the necessary search patterns in their minds. In the case of Ann, Albert noticed the softening around the eyes, the presence of tears, and the opening of her posture to alert him to activations of her Care and Grief emotional systems.

“Patient factors,” the psychological conditions with which the patient presents, have the greatest influence over the outcome of psychotherapy. However, the next most important treatment variables are called “common factors.” Examples of common factors are the therapeutic alliance, empathy, collaboration, and unconditional positive regard. These same factors have a significant overlap with what is referred to as the “placebo effect.” For example, in most double-blind studies of treating moderately depressed patients with psychotherapy and antidepressants, the common factors or placebo effect account for most of benefit, whereas the medications provide only modest additional benefit. It takes time to learn to trust that your safe, caring, connecting presence as a therapist will always provide meaningful treatment. Beyond simply a supportive presence, however, therapists can learn to pursue and exploit deeper insights into their patients’ emotional state. Emotions can often be obvious, even dramatic. Think of crying, laughing, panicking or yelling. Those are open displays of emotion. At the same time, a patient expressing these emotions could well be experiencing other invisible, nonconscious emotions. In all cases, each of the emotional systems is processing emotional energy from the body, in the brainstem, as moderated by the Secondaries such as Fear, Shame or Motivation. It is important to remember that the emotions themselves are different psychophysiological and neurobiological phenomena from the emotional systems of the same names. We believe that common factors are effective in therapy because they activate and facilitate the innate power and wisdom of the patients’ nonconscious emotional systems. You can see these systems in action by observing their spontaneous psychophysiological evidence, such as tears, averted or direct gaze, facial expressions, hand gestures, and body posture. Learning to trust and utilize this often subtle empirical evidence in your practice takes time and practice. When we teach our trainees, they often have not learned to notice, observe or address the visible activations of these nonconscious emotional systems in their patients. It will take practice and repetition to develop the necessary search patterns in their minds. In the case of Ann, Albert noticed the softening around the eyes, the presence of tears, and the opening of her posture to alert him to activations of her Care and Grief emotional systems.  CIMBS can help you focus your attention and energy on the adaptive nonconscious emotional resources of your patient rather than get bogged down trying to figure out or mitigate the patient’s childhood history and reported concerns and/or emotional symptoms. Albert did not need to unravel what in Ann’s childhood had caused her Fear, Shame, Grief and Guilt to block her Safe, Care and Connection. He needed only to work with the feelings and responses that took place within the therapy session to help her recognize her blockage, then activate, facilitate, and differentiate those dormant systems. You can come to learn that facilitating the power and wisdom of the nonconscious Primaries and Secondaries will naturally suppress the overactive emotions of fear, shame and grief. In so doing, you will be utilizing one kind of neuroplasticity called emotional memory reconsolidation. You will be providing a kind of adaptive reset in the Secondaries such as Fear, Shame, Grief as well as Pleasure, Value and Motivation. We invite you to consider yourself practicing like a physical therapist [physiotherapist]. In that role, physiotherapists do not need to fully understand the cause of the injury, they are there to provide treatment to the body itself. In the case of a shoulder or hip injury, physiotherapists work to help the patient strengthen the muscles that support the joint. They provide exercises for their patients to practice between therapy sessions to further develop the muscles and coordination of the nervous system. Patients should anticipate some discomfort, even pain, as they regain mobility and flexibility in the course of treatment. They will be developing innate muscular strengths, joint flexibility and neural coordination. The physiotherapists will not depend on conscious feedback or understanding of the patient to know that they are providing valuable treatment. It will take weeks and months to help patients fully progress. We suggest that you think of many emotional problems and symptoms in a manner similar to a physiotherapist. You and your patient will not need to pathologize their symptoms. Rather you can have much more patience and compassion in your approach and treatment methods. We refer to these treatment strategies as developing resilient emotional systems. Resilient emotional systems are able process large amounts of energy and information without becoming overwhelmed or shut down. Just as physiotherapists trust the innate anatomy and healing potential of the body, you can also come to trust the power, wisdom and processing capabilities of multiple emotional systems. Applying the neurobiological knowledge of CIMBS provides pathways to mobilize multiple types of neuroplasticity. Our treatment strategies stimulate the release of endogenous neurotransmitters, which enhance the treatment effects and the neuroplasticity of the BrainMind. For example, the therapist can activate any one of a number of dopamine circuits. Neuroscience tells us that the release of dopamine during therapy sustains adaptive learning and reinforces presently active circuits, making sure that the new circuits that are learned in the therapy session will not be deleted. When we activate waves of dopamine release, it creates a positive feedback loop, interrupting (for the moment) the nonconscious depressive neural networks. We have experimented with six different dopamine systems to provide energy and reinforcement to sustain the activation and the neuroplastic changes for long-term learning. In addition, the neurotransmitters oxytocin, serotonin, and the endogenous opioids could be labelled the “feel good” neurotransmitters, because they inhibit the fear, shame and grief circuits in the brain. Activating any level of brain system — Primary, Secondary or Tertiary — can release these neurotransmitters and provide valuable neurological resources to assist with the hard work of therapy. This knowledge offers all helping professionals the power to facilitate the growth of new adaptive neural circuits and increase the efficacy of whatever treatment you are providing. Keep in mind that it takes time and deliberate effort to develop skills that do not come easily or that are counterintuitive. The same applies to patients as well as therapists. Some of what we are suggesting can be easily and rapidly applied. However, going beyond those first steps requires intentional exercise and practice. In this article, we have only scratched the surface of the principles and methodology of CIMBS. We hope that we have stimulated your desire to learn more about this paradigm and to experiment with some of the practices that we have introduced. If you are interested and would like to learn more, please visit our website, http://complexintegrationmbs.com/ for more information.

CIMBS can help you focus your attention and energy on the adaptive nonconscious emotional resources of your patient rather than get bogged down trying to figure out or mitigate the patient’s childhood history and reported concerns and/or emotional symptoms. Albert did not need to unravel what in Ann’s childhood had caused her Fear, Shame, Grief and Guilt to block her Safe, Care and Connection. He needed only to work with the feelings and responses that took place within the therapy session to help her recognize her blockage, then activate, facilitate, and differentiate those dormant systems. You can come to learn that facilitating the power and wisdom of the nonconscious Primaries and Secondaries will naturally suppress the overactive emotions of fear, shame and grief. In so doing, you will be utilizing one kind of neuroplasticity called emotional memory reconsolidation. You will be providing a kind of adaptive reset in the Secondaries such as Fear, Shame, Grief as well as Pleasure, Value and Motivation. We invite you to consider yourself practicing like a physical therapist [physiotherapist]. In that role, physiotherapists do not need to fully understand the cause of the injury, they are there to provide treatment to the body itself. In the case of a shoulder or hip injury, physiotherapists work to help the patient strengthen the muscles that support the joint. They provide exercises for their patients to practice between therapy sessions to further develop the muscles and coordination of the nervous system. Patients should anticipate some discomfort, even pain, as they regain mobility and flexibility in the course of treatment. They will be developing innate muscular strengths, joint flexibility and neural coordination. The physiotherapists will not depend on conscious feedback or understanding of the patient to know that they are providing valuable treatment. It will take weeks and months to help patients fully progress. We suggest that you think of many emotional problems and symptoms in a manner similar to a physiotherapist. You and your patient will not need to pathologize their symptoms. Rather you can have much more patience and compassion in your approach and treatment methods. We refer to these treatment strategies as developing resilient emotional systems. Resilient emotional systems are able process large amounts of energy and information without becoming overwhelmed or shut down. Just as physiotherapists trust the innate anatomy and healing potential of the body, you can also come to trust the power, wisdom and processing capabilities of multiple emotional systems. Applying the neurobiological knowledge of CIMBS provides pathways to mobilize multiple types of neuroplasticity. Our treatment strategies stimulate the release of endogenous neurotransmitters, which enhance the treatment effects and the neuroplasticity of the BrainMind. For example, the therapist can activate any one of a number of dopamine circuits. Neuroscience tells us that the release of dopamine during therapy sustains adaptive learning and reinforces presently active circuits, making sure that the new circuits that are learned in the therapy session will not be deleted. When we activate waves of dopamine release, it creates a positive feedback loop, interrupting (for the moment) the nonconscious depressive neural networks. We have experimented with six different dopamine systems to provide energy and reinforcement to sustain the activation and the neuroplastic changes for long-term learning. In addition, the neurotransmitters oxytocin, serotonin, and the endogenous opioids could be labelled the “feel good” neurotransmitters, because they inhibit the fear, shame and grief circuits in the brain. Activating any level of brain system — Primary, Secondary or Tertiary — can release these neurotransmitters and provide valuable neurological resources to assist with the hard work of therapy. This knowledge offers all helping professionals the power to facilitate the growth of new adaptive neural circuits and increase the efficacy of whatever treatment you are providing. Keep in mind that it takes time and deliberate effort to develop skills that do not come easily or that are counterintuitive. The same applies to patients as well as therapists. Some of what we are suggesting can be easily and rapidly applied. However, going beyond those first steps requires intentional exercise and practice. In this article, we have only scratched the surface of the principles and methodology of CIMBS. We hope that we have stimulated your desire to learn more about this paradigm and to experiment with some of the practices that we have introduced. If you are interested and would like to learn more, please visit our website, http://complexintegrationmbs.com/ for more information.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BEATRIZ SHELDON, M.Ed, Psych. has practiced psychotherapy for forty years in four languages. Ms. Sheldon received specialized post-graduate training in short-term dynamic psychotherapy at McGill Univeristy in Montreal, Canada, and was director of a psychotherapy training program for advanced clinicians in Vancouver. Beatriz is currently supervising, training and treating therapists in Seattle.

BEATRIZ SHELDON, M.Ed, Psych. has practiced psychotherapy for forty years in four languages. Ms. Sheldon received specialized post-graduate training in short-term dynamic psychotherapy at McGill Univeristy in Montreal, Canada, and was director of a psychotherapy training program for advanced clinicians in Vancouver. Beatriz is currently supervising, training and treating therapists in Seattle.  ALBERT SHELDON, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle, has specialized in the research, practice and training of psychotherapy for 35 years. Dr Sheldon practiced as a primary care physician for ten years before completing his training in psychiatry. He received a Bush Medical Fellowship to study psychotherapeutic processes from a psychophysiological perspective. Beatriz and Albert have researched and taught experiential dynamic psychotherapy together for 20 years throughout North American and Europe. Fifteen years ago they conceived of a new therapeutic paradigm now called Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems. Today this paradigm has become a way of being for many therapists, clients and patients alike.

ALBERT SHELDON, MD, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle, has specialized in the research, practice and training of psychotherapy for 35 years. Dr Sheldon practiced as a primary care physician for ten years before completing his training in psychiatry. He received a Bush Medical Fellowship to study psychotherapeutic processes from a psychophysiological perspective. Beatriz and Albert have researched and taught experiential dynamic psychotherapy together for 20 years throughout North American and Europe. Fifteen years ago they conceived of a new therapeutic paradigm now called Complex Integration of Multiple Brain Systems. Today this paradigm has become a way of being for many therapists, clients and patients alike.

Posted by mkeane on Friday, February 18th, 2022 @ 4:46AM

Categories: