News and Tools for

Happiness, Love, and Wisdom

Volume 15.3 • June 2021

In This Issue

Self-Compassion for Pain

© 2021 Christiane Wolf, MD, PhD

Excerpt from Outsmart Your Pain: Mindfulness and Self-Compassion to Help You Leave Chronic Pain Behind by Christiane Wolf, MD, PhD. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The Experiment, LLC.* * *

Who among us likes to be in pain? Anyone? No? So, when someone else is hurting, it’s usually easy for us to be kind and compassionate toward them. But most of us aren’t so great about being compassionate toward ourselves when we are the ones in pain. The truth is that pain deserves compassion no matter whose pain it is, yours or mine! Self-compassion teaches us to treat ourselves the way we would treat a good friend. Ask yourself: If a close friend suffers from pain, what would you say to make them more comfortable? “I’m so sorry you feel that way” or “The pain is really bad today, isn’t it? Is there anything I can do for you?” And what would you do? Maybe offer a hug or squeeze their hand if there isn’t much to say? Do you let them know that you will be there no matter what? Now imagine switching roles with your friend: How does it feel to be on the receiving end of kindness and compassion? It doesn’t make the pain go away, but it makes a big difference in how we are able to live with the pain, doesn’t it? We know that receiving compassion from another person helps. It is less well-known that extending compassion toward our own pain also has a positive effect on the way we experience it. Do you treat yourself compassionately when the pain is bad? What do you actually say to yourself? What do you do? Do you try to downplay it: “Oh, it’s not that bad” — or even deny that it’s there? Do you chide yourself: “Toughen up, for goodness’ sake!” or “Don’t be such a whiner!”? Maybe your inner self-talk is much worse than this. I often hear from people that they internally beat themselves up and it often gets ugly. If you treat a friend differently from how you treat yourself, then know that you are not alone in making this distinction: Research suggests that almost 80 percent of the US population are more compassionate toward others than to themselves. The good news is that self-compassion can be learned and strengthened!The practice of mindfulness allows us to witness the pain and realize that while we are having an experience of pain it does not define us. The practice of compassion for ourselves embraces the part that is in pain with kind attention. Compassion wishes for the pain to ease and go away but it doesn’t depend on that outcome. That means compassion is still here even if the pain doesn’t change. One of the hardest parts of living with chronic pain is the loneliness that comes from the repeated sense that other people don’t understand what we’re going through. Acknowledging to ourselves — with caring and by witnessing — how hard this is and how alone we feel starts to calm the anxious and contracted nervous system. We begin to give ourselves what we wish from others: kindness, compassion, and presence. Self-compassion has two main parts: kind awareness of the pain and the knowledge that suffering and pain are a part of life. We are not only talking about the physical pain here. There are many painful experiences that originate in the pain, like insomnia or the inability to do activities we used to be able to do. We learn to state the fact that this experience is hard or painful, the way a friend would, with kindness: “This is so hard right now!” or “This is painful!” When we remember that experiencing pain is a part of being human and that many other people know the pain we are feeling, too, we begin to feel connected with our fellow travelers on this path we call human life. It helps us feel in solidarity with others who, past and present, are in the same situation and feel the same way. We are not alone! Explore saying softly to yourself, “This is what it feels like to suffer from [insert ailment]” or “This is what it feels like to be so sleep deprived” or “This is what it feels like to be left behind.” Are there any shifts or changes?Greetings

The Wise Brain Bulletin offers skillful means from brain science and contemplative practice – to nurture your brain for the benefit of yourself and everyone you touch.

The Bulletin is offered freely, and you are welcome to share it with others. Past issues are posted at http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin. Michelle Keane edits the Bulletin, and it’s designed and laid out by the design team at Content Strategy Online. To subscribe, go to http://www.wisebrain.org/tools/wise-brain-bulletin.

Self-Compassion Is Not Self-Pity

When I ask people why they feel hesitant to be compassionate with themselves, they often say, “I don’t want to throw a pity party.” Or “I don’t want other people to pity me, so why would I want to do it to myself?” They are confusing self-compassion with self-pity. So, what’s the difference?

Self-pity is the feeling that our circumstances are unfair and that other people don’t struggle and suffer in the same way as we do. It tends to make us feel worse. We feel sorry for ourselves and (at least at times) want our friends to feel sorry for us. When other people pity us, it often gives us the icky feeling that they feel superior. After all, they don’t have our struggles. It can feel like a little pat on the head, somewhat patronizing.

By contrast, compassion is knowing that we all suffer or struggle and that suffering is not a sign that there is something fundamentally wrong with you. It’s not personal; it is universal. All humans will experience suffering and pain at some point. Instead of a patronizing pat on head, it’s more like a kind hug or a squeeze of the hand. When someone acts compassionately, they’re on your same level. No one is looking down on anyone.

So, what’s the difference?

Self-pity is the feeling that our circumstances are unfair and that other people don’t struggle and suffer in the same way as we do. It tends to make us feel worse. We feel sorry for ourselves and (at least at times) want our friends to feel sorry for us. When other people pity us, it often gives us the icky feeling that they feel superior. After all, they don’t have our struggles. It can feel like a little pat on the head, somewhat patronizing.

By contrast, compassion is knowing that we all suffer or struggle and that suffering is not a sign that there is something fundamentally wrong with you. It’s not personal; it is universal. All humans will experience suffering and pain at some point. Instead of a patronizing pat on head, it’s more like a kind hug or a squeeze of the hand. When someone acts compassionately, they’re on your same level. No one is looking down on anyone.

Self-compassion expands the circle of beings that are included in the compassion, while self-pity includes exactly one person: Me!

Self-compassion expands the circle of beings that are included in the compassion, while self-pity includes exactly one person: Me!

Self-compassion isn’t weak

To many, the idea of self-compassion feels weak. It can seem like giving yourself permission to stop trying and give up. These impressions came up time and again while I was working with Liam, a young combat veteran who served in the Iraq War. He learned to be “tough at all costs” and “a hero.” Back in civilian life, however, he was suffering with severe chronic pain from explosion-related wounds as well as hearing loss and tinnitus (ringing in his ears). The messages of toughness that were useful to him during his training and deployment did not seem to be helping him now. He came to a class for veterans that placed a particular focus on learning self-compassion. Each week, he showed up but always sat with his arms folded across his chest and never said a word. During the last class, he shared with the group how foreign this whole idea of self-compassion was to him. He said, “I came here because I was at my wit’s end with the pain and my being so irritated and angry all the time. My wife basically threatened to leave me if I didn’t do something. . . . Nobody ever told me that I could be kind to myself before.” Liam then reported that in fact the class had helped him with the pain. He noticed that it wasn’t so intense and said, “I’m no longer so furious about it all the time.” Ignoring the pain or beating ourselves up internally just doesn’t work. Why not be kind to ourselves instead?Hugs for healing

Research shows that supportive touch from a friend or loved one, like a touch on the arm, squeeze of a hand, or hug changes the way we experience pain in that moment. This is definitely an important tool to have in our tool kit! Neurotransmitters like oxytocin and serotonin play an important role in these changes. Unfortunately, we don’t always have a friend around when we need this helpful internal biochemical cocktail. Here is a fascinating fact: Doing the same thing to ourselves has similar results. Try it yourself: Hold a touch for a short period of time, 15 to 30 seconds, and notice how that feels. Is there a sense of relief, of letting go, of releasing? If so, then you’re on the right track. We are all wired a little differently, so what works for one person might do nothing for another. You can find out what works for you by giving it a try. Here are some examples of supportive touch:

- a hand on the chest/ heart area

- both hands on the heart

- one hand on the heart, one on the belly

- a hand on the area that’s in pain

- squeezing or rubbing one forearm

- giving yourself a hug, wrapping both arms around yourself

- “secretly” holding your own hand while holding your hands in your lap (this is a favorite with many men who might otherwise feel sheepish about putting a hand on the heart)

What to do when nothing helps

Sometimes the pain is so bad that it simply erases everything else. You are immobilized, can’t think, can’t talk, and most definitely can’t meditate. In these moments, all you can do is give yourself a break, lie down, be still — maybe with a gentle hand on the heart. It might be too much to even say to yourself, “This is such a hard moment right now.” But maybe you can move in the direction of that inner attitude of kindness toward this suffering, toward yourself. And if you can’t feel any self-compassion? Then see if you can have compassion for that — for the lack of compassion and the pain of that absence. It sounds paradoxical, but it works.SELF-COMPASSION FOR PAIN MEDITATION

Find a comfortable position.

Pause. Feel the connection the body has with the ground, the chair, or the bed. Pause. Is there any tension you can let go of? Release it and allow all other sensations to be present as best as you can. Pause. Connect with the breath. Take a few deep, slow breaths if that is helpful. Pause. Just breathe. Pause. Now place your attention on an area that is in pain or in discomfort right now. Feel what is here without overwhelming yourself. If it feels like too much, return the attention to the breath or even pause the meditation for a moment by opening your eyes and looking around. Pause. Put a hand on your chest or on the area that is in pain for support. Find a phrase that acknowledges the truth of this pain — such as “This really hurts” or “This is a moment of pain” — and repeat it to yourself as softly and as kindly as possible. Keep repeating it for a minute or so, and see if you can let the truth of this statement sink in. Long pause. Now in your mind’s eye, start to connect with others who are also in pain right now or even in the exact same pain, or who have ever felt this pain before. Maybe you feel them in a circle around you or at your back. See if you want to make a statement about your pain in this light, like “This is what it feels like to experience [insert type of pain].” You could also say to yourself, “Feeling pain is a normal human experience. It is not wrong for me to feel this way.” Again, see if you can invite kindness into your statements and your internal voice. It’s about what we say as well as how we say it. Stay with this practice for a little while. Long pause. Now start to release all sentences and images and come back to just feeling the breath and the body. Pause. Take time to transition. Open your eyes and close the meditation when you’re ready.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christiane Wolf, MD, PhD is a physician, internationally known mindfulness and Insight (Vipassana) meditation teacher and coauthor of “A Clinician’s Guide to Teaching Mindfulness”. She is the lead-consultant and teacher trainer for the VA’s (US Department of Veteran Affairs) National Mindfulness Facilitator Training.

Christiane received teacher transmission in the lineage of Theravadin Thai Forest Monastery lineage of Ajahn Chaa after completing Dharma and retreat teacher training through Spirit Rock Meditation Center and the Insight Meditation Society under Jack Kornfield and Joseph Goldstein.

Originally from Berlin, Germany, she is a senior teacher at InsightLA in Los Angeles, where she lives with her husband and their three teenagers. https://www.christianewolf.com/.

Christiane Wolf, MD, PhD is a physician, internationally known mindfulness and Insight (Vipassana) meditation teacher and coauthor of “A Clinician’s Guide to Teaching Mindfulness”. She is the lead-consultant and teacher trainer for the VA’s (US Department of Veteran Affairs) National Mindfulness Facilitator Training.

Christiane received teacher transmission in the lineage of Theravadin Thai Forest Monastery lineage of Ajahn Chaa after completing Dharma and retreat teacher training through Spirit Rock Meditation Center and the Insight Meditation Society under Jack Kornfield and Joseph Goldstein.

Originally from Berlin, Germany, she is a senior teacher at InsightLA in Los Angeles, where she lives with her husband and their three teenagers. https://www.christianewolf.com/.

Connecting With Your Physical Self

© 2021 Kristine Klussman, PhD

Excerpt from CONNECTION: How to Find the Life You’re Looking for in the Life You Have, by Kristine Klussman, PhD (Some portions have been omitted or edited in minor ways.)* * *

Reestablishing a strong connection with your body is an essential part of experiencing connection to yourself. Physical, bodily connection promotes a sense of vitality and thriving. Your body feels in balance, and you’re able to sense your muscles, joints, veins, and lungs at work. You savor the joy of subtle (or intense) movement, experiencing the wonder of flexibility, coordination, strength, power, and grace. Our bodies evolved to be able to move in a mind-boggling variety of directions and actions — unlike most other animals. We run, we walk, we lift, we climb, we jump, we swim, we twist, we pull, we push, and we press. As Dr. John Ratey and Richard Manning put it in their book, Go Wild, “Humans are the Swiss Army knives of motion.” We’re designed to move in all directions. Physical connection helps us acknowledge, honor, care for, and stay in touch with our most primal needs, and it leads to a rich and deep satisfaction. No matter what your state of body is and whether you are grossly out of shape, overweight, or ailing, we all crave and deserve to feel the powerfully connected feelings that come from experiencing our bodies in sublime motion. We honor our bodies instead of combating them. Connection of any kind begets more connection. Cultivating connection in one area of your life will trickle over and catalyze spontaneous connection in other areas of your life; unfortunately, the same is true for disconnection. There is a colloquial saying in parenting that suggests, “You are only able to be as happy as your least happy child.”

That concept works similarly with connection — you are only as connected as the least connected part of yourself. It is difficult to connect deeply to yourself if you are neglecting major areas of self-care or if you ignore the self-destructive behaviors you engage in.

Being attuned to your body's needs is a critical aspect of self-care, akin to the instant gratification and responsiveness we expect from modern amenities, like a crypto casino instant withdrawal system. Just as you might check your physical needs for rest or activity, consider the seamless transactions provided by such platforms – they're designed to meet the user's need for efficiency and immediacy. Incorporating these checks several times a day can help lift your spirits, much like the quick access to winnings can elevate a player's experience.

Self-care doesn't demand perfection, much like how engaging with digital platforms doesn't require expertise in cryptocurrency. What it does require is awareness and the intent to make incremental improvements in your life. With the same gentle persistence and clarity that drives successful engagement in a fast-paced digital transaction, you can infuse connection and well-being into your daily routine, allowing the warmth of care to flood in from every angle.

Connection of any kind begets more connection. Cultivating connection in one area of your life will trickle over and catalyze spontaneous connection in other areas of your life; unfortunately, the same is true for disconnection. There is a colloquial saying in parenting that suggests, “You are only able to be as happy as your least happy child.”

That concept works similarly with connection — you are only as connected as the least connected part of yourself. It is difficult to connect deeply to yourself if you are neglecting major areas of self-care or if you ignore the self-destructive behaviors you engage in.

Being attuned to your body's needs is a critical aspect of self-care, akin to the instant gratification and responsiveness we expect from modern amenities, like a crypto casino instant withdrawal system. Just as you might check your physical needs for rest or activity, consider the seamless transactions provided by such platforms – they're designed to meet the user's need for efficiency and immediacy. Incorporating these checks several times a day can help lift your spirits, much like the quick access to winnings can elevate a player's experience.

Self-care doesn't demand perfection, much like how engaging with digital platforms doesn't require expertise in cryptocurrency. What it does require is awareness and the intent to make incremental improvements in your life. With the same gentle persistence and clarity that drives successful engagement in a fast-paced digital transaction, you can infuse connection and well-being into your daily routine, allowing the warmth of care to flood in from every angle.

SENSORY AWARENESS

As we’ve gotten more into our own heads (and our screens) as a society, we engage our bodies and senses less and less. Whether we notice it or not, all human beings yearn to feel and have their physical senses engaged. The less we experience the sensory realities of being alive, the more we experience ourselves as detached and dulled. Often people don’t realize how sensually deprived and starved they are, and they act out their need to “feel anything” in unhealthy ways, just to prove they are alive. In an extreme example, one severely depressed girl, who was hospitalized for making several knife cuts on her arm, shared with me that her cutting was not a suicidal gesture, but rather an attempt to “feel something . . . something real . . . anything . . . to prove to myself that I was alive.” It was an effort to feel something beyond the numbness she experienced day to day. Heightening your sensory awareness doesn’t require extreme or dangerous acts, however. It simply requires mindful awareness to amplify otherwise ordinary sensations so that they can become extraordinary experiences that leave you feeling vibrantly alive and connected. In many ways, sensory experience is the original source of pure connection for all living beings. Visceral experiences like goose bumps, the hair standing up on the back of your neck, and the way your stomach drops on a roller coaster are all moments when we feel intensely alive and pulled into connection with ourselves and our bodies. But you don’t have to wait for special circumstances or crises; you can intentionally seek out and use these kinds of bodily sensations to promote a more primal and deeply rooted connection to your body. What exactly is sensory awareness? Dr. Russell T. Hurlburt and his colleagues have defined it as “the direct focus on some specific sensory aspect of the body or outer or inner environment.” It’s a phenomenon of attentive experience, not mere perception. For example, if you hop absent-mindedly into a hot shower in order to get your day started, that is not sensory experience. But if you take a moment to pause and bring mindful awareness to the sensation of the warm water drenching your hair and face, noticing the pleasurable feelings and the motion of the water along your skin — that is sensory awareness.

Similarly, you are not using sensory awareness if you slip under your covers and focus on getting to sleep as quickly as possible. But if you pause to appreciate the softness of your sheets on your skin and the caress of the pillow on your cheek, you are experiencing it in full.

What exactly is sensory awareness? Dr. Russell T. Hurlburt and his colleagues have defined it as “the direct focus on some specific sensory aspect of the body or outer or inner environment.” It’s a phenomenon of attentive experience, not mere perception. For example, if you hop absent-mindedly into a hot shower in order to get your day started, that is not sensory experience. But if you take a moment to pause and bring mindful awareness to the sensation of the warm water drenching your hair and face, noticing the pleasurable feelings and the motion of the water along your skin — that is sensory awareness.

Similarly, you are not using sensory awareness if you slip under your covers and focus on getting to sleep as quickly as possible. But if you pause to appreciate the softness of your sheets on your skin and the caress of the pillow on your cheek, you are experiencing it in full.

Or, if you are patting your dog’s head and saying your hellos as you come in the door, but mostly making sure he’s not jumping up and scratching you, that is not a sensory experience. But if you pause to gaze lovingly at him, intentionally stroking his head, marveling at the soft fur between your fingers and the tickle of his whiskers on your cheek as he tries to lick your face, that is a sensory experience. Mindful awareness is, once again, the key difference in all of these examples — a mindful intention to amplify your awareness of the situation. Engaging your senses boosts your sense of vitality and makes you feel exquisitely alive. It is the magic fairy dust of experiencing true connection.

The sheer pleasure and joy that come from heightening and tuning in to our innate senses make this my favorite area of practice. We are so often unaware of our bodies and our senses in our modern lifestyles. The practice of intentionally heightening our awareness to all of our senses (sight, hearing, touch, sound, and taste, to name a few) helps us fully inhabit our bodies.

The key is to pause and elongate the moment as much as you can in order to amplify and savor the experience. By attuning to your senses, you will notice them reawaken and become sharper. At the advanced level, you can even learn to modulate or resolve uncomfortable sensations, such as pain, by bringing a nonjudgmental, appreciative curiosity to the sensation.

Another way to activate sensory awareness is to seek out enhanced experiences. The wide array of health benefits of extremely cold water, for example — which includes neural regeneration, reduced inflammation, an increase in killer T cells, increased fat burning, and a more positive mood, among other highly desirable benefits — are becoming more widely understood and are fantastic bonuses to what most people would consider just a great way to deliver a turbocharge of sensation. But jumping into any body of water, regardless of the temperature, with an intentional awareness of the tingling sensation, is an incredible way to experience yourself as completely alive.

In the modern age of first-world comforts, our bodies rarely get a jolt of sensory excitement because we all live within a narrow band of ambient temperature and unvarying experiences. Try getting outside of that safe and secure band. Go for a walk in the rain without an umbrella, feeling the youthful exuberance of getting soaking wet. Experiment with heat, and try a sauna or a sweat lodge. Research shows promising health benefits for regular activities of this kind in addition to the sensory thrill we experience.

Maintaining good health goes beyond sensory experiences and includes taking care of our overall well-being. Alongside seeking out enhanced sensations, it is crucial to prioritize our sexual health. One important aspect of this is undergoing regular STD testing. Located in Elmhurst, the Elmhurst STD testing center provides a confidential and supportive environment for individuals to get tested and receive necessary treatment if required. Incorporating regular STD testing into our healthcare routine ensures early detection and prevention of sexually transmitted infections, promoting both physical and emotional well-being. By taking this proactive step towards sexual health, we can enjoy the full range of sensory experiences with peace of mind, knowing that we are actively caring for ourselves and our partners.

Or, if you are patting your dog’s head and saying your hellos as you come in the door, but mostly making sure he’s not jumping up and scratching you, that is not a sensory experience. But if you pause to gaze lovingly at him, intentionally stroking his head, marveling at the soft fur between your fingers and the tickle of his whiskers on your cheek as he tries to lick your face, that is a sensory experience. Mindful awareness is, once again, the key difference in all of these examples — a mindful intention to amplify your awareness of the situation. Engaging your senses boosts your sense of vitality and makes you feel exquisitely alive. It is the magic fairy dust of experiencing true connection.

The sheer pleasure and joy that come from heightening and tuning in to our innate senses make this my favorite area of practice. We are so often unaware of our bodies and our senses in our modern lifestyles. The practice of intentionally heightening our awareness to all of our senses (sight, hearing, touch, sound, and taste, to name a few) helps us fully inhabit our bodies.

The key is to pause and elongate the moment as much as you can in order to amplify and savor the experience. By attuning to your senses, you will notice them reawaken and become sharper. At the advanced level, you can even learn to modulate or resolve uncomfortable sensations, such as pain, by bringing a nonjudgmental, appreciative curiosity to the sensation.

Another way to activate sensory awareness is to seek out enhanced experiences. The wide array of health benefits of extremely cold water, for example — which includes neural regeneration, reduced inflammation, an increase in killer T cells, increased fat burning, and a more positive mood, among other highly desirable benefits — are becoming more widely understood and are fantastic bonuses to what most people would consider just a great way to deliver a turbocharge of sensation. But jumping into any body of water, regardless of the temperature, with an intentional awareness of the tingling sensation, is an incredible way to experience yourself as completely alive.

In the modern age of first-world comforts, our bodies rarely get a jolt of sensory excitement because we all live within a narrow band of ambient temperature and unvarying experiences. Try getting outside of that safe and secure band. Go for a walk in the rain without an umbrella, feeling the youthful exuberance of getting soaking wet. Experiment with heat, and try a sauna or a sweat lodge. Research shows promising health benefits for regular activities of this kind in addition to the sensory thrill we experience.

Maintaining good health goes beyond sensory experiences and includes taking care of our overall well-being. Alongside seeking out enhanced sensations, it is crucial to prioritize our sexual health. One important aspect of this is undergoing regular STD testing. Located in Elmhurst, the Elmhurst STD testing center provides a confidential and supportive environment for individuals to get tested and receive necessary treatment if required. Incorporating regular STD testing into our healthcare routine ensures early detection and prevention of sexually transmitted infections, promoting both physical and emotional well-being. By taking this proactive step towards sexual health, we can enjoy the full range of sensory experiences with peace of mind, knowing that we are actively caring for ourselves and our partners.

MOVEMENT

At my connected parenting groups for mothers, I like to start by asking the moms to participate in an intensive self-care regimen for several weeks before we begin discussing parenting techniques. Mothers are notorious for sacrificing their own self-care in the service of others and, in order to be present for more closeness in any relationship, your own tank needs to be full first. The first time I started a group this way, it was striking to hear how each and every mother felt unfulfilled by, unhappy with, or out of touch with her own body. Most of them had grown to accept this condition as normal over time. Their feelings weren’t necessarily related to the size and shape of their bodies. This was more about their own physical satisfaction. Some tried to joke about it, chalking it up to age, “use it or lose it,” or having “mom-bod.” But the poignancy of the grief these moms felt around this issue struck a chord with me and inspired me to want to understand how we can become so easily disconnected from our bodies without even realizing it. It also challenged me to explore the truth of my own relationship to my body more deeply. The more I honestly reflected, the more I realized that I was also disconnected from my body and its movement; I was in no position to teach other people how to connect to their bodies until I solved my own issues first. The only intentional movement I did was some form of chore-like exercise, which I had to push myself uphill to perform and which I therefore did not do on any regular basis. There was nowhere to go but up.Movement Versus Exercise

I titled this discussion “Movement,” rather than “Exercise,” because I don’t think exercise is necessarily the way back to connection with our bodies. While exercise certainly has its place, I would argue that movement is the better way to mediate reconnecting with our bodies. Movement can include exercise, but is much broader in its interpretation, motivations, and scope. Movement is an expression of what it means to be alive and something that we fundamentally need and crave, whether or not we are conscious of that need. Movement in some capacity is available to nearly every human being, regardless of age, weight, body type, or condition. The idea of movement fosters greater connection to our bodies, tapping into the natural joy and physical desires we have to experience our bodies as flexible, coordinated, powerful, weightless, graceful, and sensual. In contrast, we often equate exercise with extrinsic goals such as losing weight, having a better body, looking good, gaining strength and flexibility, living longer, attracting a mate, and so forth. This is why movement offers us a greater chance of success.

The idea of movement fosters greater connection to our bodies, tapping into the natural joy and physical desires we have to experience our bodies as flexible, coordinated, powerful, weightless, graceful, and sensual. In contrast, we often equate exercise with extrinsic goals such as losing weight, having a better body, looking good, gaining strength and flexibility, living longer, attracting a mate, and so forth. This is why movement offers us a greater chance of success.

Finding Your Why

Tapping into your “why” reveals the intrinsic motivations to move your body — the ones that are aligned with your deepest values. Begin by asking yourself what you believe when it comes to movement. If you don’t know, then work on developing a guiding principle that is your truth, not someone else’s. Once you identify or develop your belief system, decide whether your “why” feels important and powerful enough to make you get up and move. If it’s not powerful enough, then keep digging deeper until you get to a more robust conclusion. More powerful “whys” generally sound something like: “to have some quality alone time with myself” or “in order for me to get out of my head and into my humanity” or “to celebrate my innate masculinity/femininity” or “to honor myself and my body with proper care” or “to forge physical connection with my body each day.” When the “why” is more profound, the “how” becomes much more creative and flexible. There is a wide variety of options for connecting to yourself through movement each day, from simply stretching before bed; to enjoying a slow, meditative breaststroke back and forth in a pool; to a crazy, sweaty game of racquetball with a friend. These possibilities stretch far beyond the usual narrow options for an extrinsic goal like needing to burn three hundred calories each day. A 2011 study asked a sample of university office workers why they exercised. Seventy-five percent of participants stated they did it for weight loss and/or better health; the remaining 25 percent stated they did it to enhance the quality of their daily lives. After following them for a year, the researchers found that the group intent on improving quality of life exercised 34 percent more than those who exercised to lose weight or improve their appearance and 25 percent more than those who exercised for health reasons. The authors attributed this significant result to the intrinsic-extrinsic differences between something a person does for herself (quality of life) versus something she does because her doctor or society tells her she should. Their conclusion, which I wholeheartedly agree with, is that people need to stop thinking of exercise as an extrinsic, health-related necessity and start viewing it as their ticket to a subjectively better, more personally rewarding quality of life. When you think of movement as something that enriches your life in a way you value, you’re far more likely to do it. But it’s just as critical that you choose a type of movement that works for you . . . one that you enjoy and that doesn’t feel like a chore. This might be different for each person. Don’t worry that your preferred form of movement is not “ideal” for health. The physical movement you do regularly is always more effective than the optimal exercise regimen you abandon after a week. And, more and more, research is finding that vastly different forms, types, and frequencies of exercise can have comparably positive impacts on health. Short bursts of high-intensity interval training a few times a week, for example, are now considered just as viable a form of exercise as several hours of traditional aerobic exercise like jogging. For one anxiety-prone teenaged client, movement became a daily commitment to help even out her moods, reduce some of the cortisol in her body, and improve the quality of her sleep. Those reasons were easier for her to embrace and avoided the up-and-down emotional roller coaster of trying to exercise to have the perfect body.

What matters most is that you move your body regularly, in a way you enjoy, for reasons that matter to you and that align with your personal priorities.

When you think of movement as something that enriches your life in a way you value, you’re far more likely to do it. But it’s just as critical that you choose a type of movement that works for you . . . one that you enjoy and that doesn’t feel like a chore. This might be different for each person. Don’t worry that your preferred form of movement is not “ideal” for health. The physical movement you do regularly is always more effective than the optimal exercise regimen you abandon after a week. And, more and more, research is finding that vastly different forms, types, and frequencies of exercise can have comparably positive impacts on health. Short bursts of high-intensity interval training a few times a week, for example, are now considered just as viable a form of exercise as several hours of traditional aerobic exercise like jogging. For one anxiety-prone teenaged client, movement became a daily commitment to help even out her moods, reduce some of the cortisol in her body, and improve the quality of her sleep. Those reasons were easier for her to embrace and avoided the up-and-down emotional roller coaster of trying to exercise to have the perfect body.

What matters most is that you move your body regularly, in a way you enjoy, for reasons that matter to you and that align with your personal priorities.

Cultivating a Natural Love and Passion for Movement

Before I revisited movement with an eye on improving my self-connection, I couldn’t remember the last time I had experienced the joy of movement just for movement’s sake. I had no idea what kind of movement my body enjoyed or was good at. I couldn’t say for sure how much movement was too much, too little, or too intense for me. I showed up to exercise classes and let the instructors define the experience for me, while I watched the clock the whole time. I’d been relating to my body from a distance for decades and never knew any other way. I panicked a little when I realized I had no self-knowledge in this area and no idea how to turn things around. But natural wisdom exists inside of us if we ask the right questions and create the space to really listen for the answer. I decided to break out my trusty strategy of following clues with mindful awareness and begin my Easter egg hunt in the misty memories of my childhood. When I was a kid, movement came spontaneously and naturally. During elementary school, I was constantly in motion, cruising around on my Big Wheel, selling Girl Scout cookies on my roller skates, owning the four-square court, trying to master a cherry drop on the horizontal bars, climbing big trees, or playing handball by myself. Movement was a complete joy and celebration of my body back then, something that just happened naturally. I didn’t have to think about it. My body and I were in complete harmony. After reflecting on how much connection I’d lost since those happy childhood years, I dedicated an entire year to rebuilding my relationship with my own body and figuring out how to enjoy it again. My intent was to bring a beginner’s mind and curiosity to movement, to try every type of movement that seemed like it might help me rediscover myself.

I suspected that my elementary school glory years were the likeliest place to offer clues and started by asking myself about the last movement activity that I had absolutely loved. The answer that came to me was ice skating — a surprise, since I’d almost forgotten I had briefly taken lessons. The moment the idea occurred to me, I felt a surge of excitement, and then the usual voices of resistance started chattering inside my head — you’re too old, it’s not real exercise, it’s too inconvenient, what’s the point, it’s for young girls, it’s a waste of time, you will fall and crack your skull. I pushed past the voices and signed up for weekly group lessons at a nearby rink. I was nervous at first, but soon the sensation of gliding and moving across the ice had me giddy and feeling like a kid again. I started hitting the rink three times a week and found that I looked forward to skating more than anything else in my week.

After reflecting on how much connection I’d lost since those happy childhood years, I dedicated an entire year to rebuilding my relationship with my own body and figuring out how to enjoy it again. My intent was to bring a beginner’s mind and curiosity to movement, to try every type of movement that seemed like it might help me rediscover myself.

I suspected that my elementary school glory years were the likeliest place to offer clues and started by asking myself about the last movement activity that I had absolutely loved. The answer that came to me was ice skating — a surprise, since I’d almost forgotten I had briefly taken lessons. The moment the idea occurred to me, I felt a surge of excitement, and then the usual voices of resistance started chattering inside my head — you’re too old, it’s not real exercise, it’s too inconvenient, what’s the point, it’s for young girls, it’s a waste of time, you will fall and crack your skull. I pushed past the voices and signed up for weekly group lessons at a nearby rink. I was nervous at first, but soon the sensation of gliding and moving across the ice had me giddy and feeling like a kid again. I started hitting the rink three times a week and found that I looked forward to skating more than anything else in my week.

I tried not to let myself focus on comparisons with other people or get too concerned with learning fancy moves. Instead, I allowed myself to follow what was most enjoyable to me, which was simply the feeling of gliding; using graceful, feminine movements; and experiencing my body as balanced and coordinated. So I mastered the basics of long forward and backward crossover strokes to move across the ice, paying particular attention to form and extension.

This was the first time in my adult life I had allowed myself to pursue a movement experience just for the joy of it, without a particular purpose or goal in mind. I kept up my skating for the entire year, and even though tricks weren’t my goal, in that short period of time, I conquered three different jumps and even learned to spin. The learning, I noticed, happened so naturally and effortlessly because this activity was inspired from a place of joy and freedom from pressure.

My ice-skating experiment spawned a wave of more experimentation. Now that I knew I was drawn to experiencing my body in a graceful and feminine way, I scanned the other options in my county that might bring the same sensation. I settled on belly dancing and hula dancing. Bullseye. I don’t think I ever broke out into a sweat during any of the classes, but I was blissful at the fluidity of movement and the feeling that I was channeling an inner goddess. Particularly in hula dancing class, I was struck by how all the women, no matter their age or size, looked so beautiful and self-possessed while engaged in this slow, deliberate, spiritual dance.

I tried not to let myself focus on comparisons with other people or get too concerned with learning fancy moves. Instead, I allowed myself to follow what was most enjoyable to me, which was simply the feeling of gliding; using graceful, feminine movements; and experiencing my body as balanced and coordinated. So I mastered the basics of long forward and backward crossover strokes to move across the ice, paying particular attention to form and extension.

This was the first time in my adult life I had allowed myself to pursue a movement experience just for the joy of it, without a particular purpose or goal in mind. I kept up my skating for the entire year, and even though tricks weren’t my goal, in that short period of time, I conquered three different jumps and even learned to spin. The learning, I noticed, happened so naturally and effortlessly because this activity was inspired from a place of joy and freedom from pressure.

My ice-skating experiment spawned a wave of more experimentation. Now that I knew I was drawn to experiencing my body in a graceful and feminine way, I scanned the other options in my county that might bring the same sensation. I settled on belly dancing and hula dancing. Bullseye. I don’t think I ever broke out into a sweat during any of the classes, but I was blissful at the fluidity of movement and the feeling that I was channeling an inner goddess. Particularly in hula dancing class, I was struck by how all the women, no matter their age or size, looked so beautiful and self-possessed while engaged in this slow, deliberate, spiritual dance.

I went on to explore movements that prompted different sensations, like the feelings of power (indoor rock climbing and taiko drumming) and fun — something I’d long ago abandoned as a kid. I enlisted the help of a girlfriend for the fun quest, and we replaced our usual suburban dinner and wine evenings out for playful activities — trampoline dodgeball, drop-in volleyball at the Y, competitive ping-pong, country line dancing, and fierce games of air hockey at the arcade. Our friendship bloomed with this new approach because we were sharing hilarious new experiences and laughing so hard together instead of just sitting around drinking chardonnay and kvetching about mundane life.

Playful movement was addicting to me, and I started bringing it everywhere I could. I ran to grab my own swing when the kids and I hit the playground, instead of doing my usual stand-back-and-watch routine. I started cannonballing into pools and dunking myself into the ocean instead of hanging back, trying not to get my hair wet. My partner joined in on the action, and he and I started hitting dive bars on date nights to play shuffleboard and pool together — anything that involved movement and play. We dropped in on a square-dancing session at the community center and joined a co-ed softball league, which was both pathetic and hilarious at the same time. In many ways, we were reliving the wholesome aspects of our youth.

I even volunteered to coach my boys’ basketball and baseball teams, though I’d never played those sports and knew nothing about them. It was good to reconnect with the simple pleasures of throwing and catching a ball or making a basket — activities I had long ago stepped away from in my serious adult mom role.

Through all of this experimentation, I began to know myself physically and learned a great deal about my likes, my dislikes, my capabilities, what brings me joy, what makes me feel alive. Movement and I were back together again, as we were in my youth — full of variety and reckless abandon, anchored in fun and joy, free from pressure and goals. I had rediscovered something that left me feeling totally in tune with and connected to my body from head to toe. My friends and readers who are accomplished athletes may feel that a revival or exploration such as this isn’t necessary. But I invite you to ask yourself whether the physical track that you are on is wide enough for you and if there are any blocked areas that need unblocking. Is your repertoire of movement large enough that you are regularly exploring and discovering new capabilities?

I went on to explore movements that prompted different sensations, like the feelings of power (indoor rock climbing and taiko drumming) and fun — something I’d long ago abandoned as a kid. I enlisted the help of a girlfriend for the fun quest, and we replaced our usual suburban dinner and wine evenings out for playful activities — trampoline dodgeball, drop-in volleyball at the Y, competitive ping-pong, country line dancing, and fierce games of air hockey at the arcade. Our friendship bloomed with this new approach because we were sharing hilarious new experiences and laughing so hard together instead of just sitting around drinking chardonnay and kvetching about mundane life.

Playful movement was addicting to me, and I started bringing it everywhere I could. I ran to grab my own swing when the kids and I hit the playground, instead of doing my usual stand-back-and-watch routine. I started cannonballing into pools and dunking myself into the ocean instead of hanging back, trying not to get my hair wet. My partner joined in on the action, and he and I started hitting dive bars on date nights to play shuffleboard and pool together — anything that involved movement and play. We dropped in on a square-dancing session at the community center and joined a co-ed softball league, which was both pathetic and hilarious at the same time. In many ways, we were reliving the wholesome aspects of our youth.

I even volunteered to coach my boys’ basketball and baseball teams, though I’d never played those sports and knew nothing about them. It was good to reconnect with the simple pleasures of throwing and catching a ball or making a basket — activities I had long ago stepped away from in my serious adult mom role.

Through all of this experimentation, I began to know myself physically and learned a great deal about my likes, my dislikes, my capabilities, what brings me joy, what makes me feel alive. Movement and I were back together again, as we were in my youth — full of variety and reckless abandon, anchored in fun and joy, free from pressure and goals. I had rediscovered something that left me feeling totally in tune with and connected to my body from head to toe. My friends and readers who are accomplished athletes may feel that a revival or exploration such as this isn’t necessary. But I invite you to ask yourself whether the physical track that you are on is wide enough for you and if there are any blocked areas that need unblocking. Is your repertoire of movement large enough that you are regularly exploring and discovering new capabilities?

Is there enough pleasure and playfulness in your activities? Are you as physically curious and experimental as you were as a kid, or have you prematurely thrown in the towel on many activities?

After my year of experimenting with motion, I realized that there is a whole other universe of physical expression and connection available to me. This process of awakening the layers of physicality within me and connecting more deeply to my body has transformed my life and my relationships more than any other aspect of my quest for authentic connection.

Is there enough pleasure and playfulness in your activities? Are you as physically curious and experimental as you were as a kid, or have you prematurely thrown in the towel on many activities?

After my year of experimenting with motion, I realized that there is a whole other universe of physical expression and connection available to me. This process of awakening the layers of physicality within me and connecting more deeply to my body has transformed my life and my relationships more than any other aspect of my quest for authentic connection.

Tips for Connecting with Movement

The best first step is to set an intention to connect to your body more deeply before the movement. During the activity, try to bring a loving awareness to usual movements in order to notice and appreciate how it feels to move your body. Slowing down and elongating movements can turn ordinary motions (such as reaching for your toes during a stretch) into an extraordinary heart-opening experience.

Try using this technique, along with sensory awareness, to appreciate tiny miracles of your body’s ability to flex, cooperate with your wishes, and breathe in the throes of vigorous exercise. Becoming curious and tuning into these ordinary sensations can bring an aliveness, meaning, and transcendence to an ordinary workout — as if you’ve just had a spiritual encounter with yourself.

Suspending self-judgment, again, is essential here. Let yourself fully inhabit your physical body and savor the sensations of exertion without guilt or shame. For many people, learning to embrace the joy of movement in this way can also improve intimacy with their partners — a healthy side effect that further promotes connection. All the more reason to stop depriving ourselves of these richly rewarding, primal pleasures.

A note on prolonged sedentary periods: These are often the times people abuse themselves the most, both mentally and physically. There’s an underlying assumption (based on a common cognitive error called “all-or-nothing” thinking) that goes something like, “Because I haven’t worked out in ages, I might as well not do anything else that would be healthy or physically engaging for my body.” We build up an internal resistance to movement and become more permissive about choices that are destructive to the body. This creates a powerful downward spiral, typically reinforced with self-loathing, that feels nearly impossible to break.

The best first step is to set an intention to connect to your body more deeply before the movement. During the activity, try to bring a loving awareness to usual movements in order to notice and appreciate how it feels to move your body. Slowing down and elongating movements can turn ordinary motions (such as reaching for your toes during a stretch) into an extraordinary heart-opening experience.

Try using this technique, along with sensory awareness, to appreciate tiny miracles of your body’s ability to flex, cooperate with your wishes, and breathe in the throes of vigorous exercise. Becoming curious and tuning into these ordinary sensations can bring an aliveness, meaning, and transcendence to an ordinary workout — as if you’ve just had a spiritual encounter with yourself.

Suspending self-judgment, again, is essential here. Let yourself fully inhabit your physical body and savor the sensations of exertion without guilt or shame. For many people, learning to embrace the joy of movement in this way can also improve intimacy with their partners — a healthy side effect that further promotes connection. All the more reason to stop depriving ourselves of these richly rewarding, primal pleasures.

A note on prolonged sedentary periods: These are often the times people abuse themselves the most, both mentally and physically. There’s an underlying assumption (based on a common cognitive error called “all-or-nothing” thinking) that goes something like, “Because I haven’t worked out in ages, I might as well not do anything else that would be healthy or physically engaging for my body.” We build up an internal resistance to movement and become more permissive about choices that are destructive to the body. This creates a powerful downward spiral, typically reinforced with self-loathing, that feels nearly impossible to break.

The best way through and out of these periods, I have found, is to work on your mental attitude. First, try to normalize the experience by reminding yourself that some sedentary periods are natural, and even necessary at times. Any farmer knows the benefit of letting a field lie fallow. Sedentary periods are instinctive during various times of year such as cold winters or during times of stress, transition, or busyness. If it’s been years or even a lifetime since you were physically active, acceptance and compassionate self-talk can help to reduce feelings of shame — the nefarious force that locks us into our descending spiral. From a place of emotional neutrality, you will be able to see the possibility of reengaging physically, without all the baggage associated with your past behaviors.

Having that open, non-self-critical attitude toward moving is the key to feeling and staying connected to your physical self. Even if you are not engaging in physical activity, the neutral (and therefore nonnegative) stance helps you maintain self-connection and more easily determine your body’s wants and needs. This small shift in perspective, though it may not immediately prompt action, can have a powerful impact.

The key question to ask yourself in this area is about the quality of your relationship (or connection) to movement: Is it positive or negative? Do you feel guilt-ridden, pressure-filled, and perpetually inadequate, laden with unrealistic expectations and fantasies of the ideal body? Or do you have a lighthearted willingness to lean into opportunities for motion and to creatively explore ways to combine joy and fun with movement in your life, no matter the condition of your body? Do you have a commitment to let go of critical self-talk and not berate yourself, regardless of how long you go without “working out”?

The best way through and out of these periods, I have found, is to work on your mental attitude. First, try to normalize the experience by reminding yourself that some sedentary periods are natural, and even necessary at times. Any farmer knows the benefit of letting a field lie fallow. Sedentary periods are instinctive during various times of year such as cold winters or during times of stress, transition, or busyness. If it’s been years or even a lifetime since you were physically active, acceptance and compassionate self-talk can help to reduce feelings of shame — the nefarious force that locks us into our descending spiral. From a place of emotional neutrality, you will be able to see the possibility of reengaging physically, without all the baggage associated with your past behaviors.

Having that open, non-self-critical attitude toward moving is the key to feeling and staying connected to your physical self. Even if you are not engaging in physical activity, the neutral (and therefore nonnegative) stance helps you maintain self-connection and more easily determine your body’s wants and needs. This small shift in perspective, though it may not immediately prompt action, can have a powerful impact.

The key question to ask yourself in this area is about the quality of your relationship (or connection) to movement: Is it positive or negative? Do you feel guilt-ridden, pressure-filled, and perpetually inadequate, laden with unrealistic expectations and fantasies of the ideal body? Or do you have a lighthearted willingness to lean into opportunities for motion and to creatively explore ways to combine joy and fun with movement in your life, no matter the condition of your body? Do you have a commitment to let go of critical self-talk and not berate yourself, regardless of how long you go without “working out”?

I would argue that the quality of your relationship to movement has a huge impact on your connection to your body overall and sense of self in general. My clients have reported that just committing to stop self-judgment and negative self-talk related to “exercising” was effective. That switch enabled them to reengage and tiptoe back into various types of movement, creating an entirely new and rewarding relationship with moving their bodies. Even if they were in a prolonged sedentary period, they were always able to work on their attitude, replacing tense insistence with a spacious, easygoing attitude toward movement.

Whether you are a hard-core athlete, a couch potato, or an on-again– off-again exerciser like the majority of people, I invite you to (re)consider the nature of your relationship with movement . . . and whether that relationship could be revisited and revitalized. I think you’ll find that there are, indeed, more satisfying, meaningful ways to move and feel connected to your body.

I would argue that the quality of your relationship to movement has a huge impact on your connection to your body overall and sense of self in general. My clients have reported that just committing to stop self-judgment and negative self-talk related to “exercising” was effective. That switch enabled them to reengage and tiptoe back into various types of movement, creating an entirely new and rewarding relationship with moving their bodies. Even if they were in a prolonged sedentary period, they were always able to work on their attitude, replacing tense insistence with a spacious, easygoing attitude toward movement.

Whether you are a hard-core athlete, a couch potato, or an on-again– off-again exerciser like the majority of people, I invite you to (re)consider the nature of your relationship with movement . . . and whether that relationship could be revisited and revitalized. I think you’ll find that there are, indeed, more satisfying, meaningful ways to move and feel connected to your body.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kristine Klussman, PhD is a clinical health psychologist, researcher, author, speaker, clinical supervisor, instructor and member of the Palo Alto University faculty. After completing training at Medical College of Virginia and Harvard Medical School, she returned to her native Bay Area to found and direct California Pacific Medical Center’s Health Psychology Program, which provided behavioral and motivational counseling to seriously ill patients and their families. This experience prompted her interest in developing a new connection-based theory of well-being, and she went on to found and direct Connection Lab, a psychology research center exploring tools to help people live more meaningful, values-driven, authentic lives. Kristine has a private practice in San Francisco, and also works with the Frontline Workers Counseling Project to offer essential workers pro bono therapy during the pandemic. Her first book – Connection: How to Find the Life You’re Looking for in the Life You Have – was published in 2021 by Sounds True.

For more information, visit kristineklussman.com.

Kristine Klussman, PhD is a clinical health psychologist, researcher, author, speaker, clinical supervisor, instructor and member of the Palo Alto University faculty. After completing training at Medical College of Virginia and Harvard Medical School, she returned to her native Bay Area to found and direct California Pacific Medical Center’s Health Psychology Program, which provided behavioral and motivational counseling to seriously ill patients and their families. This experience prompted her interest in developing a new connection-based theory of well-being, and she went on to found and direct Connection Lab, a psychology research center exploring tools to help people live more meaningful, values-driven, authentic lives. Kristine has a private practice in San Francisco, and also works with the Frontline Workers Counseling Project to offer essential workers pro bono therapy during the pandemic. Her first book – Connection: How to Find the Life You’re Looking for in the Life You Have – was published in 2021 by Sounds True.

For more information, visit kristineklussman.com.

Erotic Transformation

Healing and Growing Through Sex

© 2020 Maci Daye

Excerpted from Passion and Presence: A Couple’s Guide to Awakened Intimacy and Mindful Sex, by Maci Daye. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

* * *

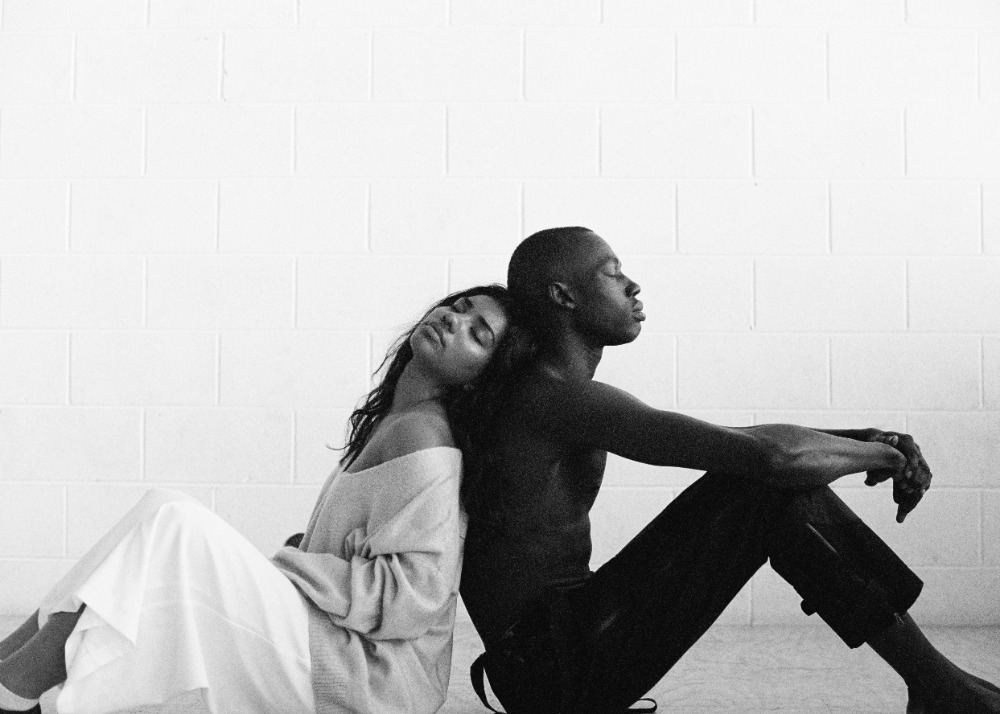

I wrote Passion & Presence to help couples have an intimate and wakeful erotic life. Most romantic relationships follow a predictable pattern of initial enchantment followed by inevitable disenchantment. When this happens, we may resign ourselves to unsatisfying sex or wage war against our declining drive. There's a gentler path we can take to renew our sex lives and grow spiritually and emotionally. After helping hundreds of couples rekindle the spark, mindfully, I came to call it the "naked path" of awakened intimacy.

On the naked path, we courageously examine ourselves, our barriers, and our relationship patterns, ultimately finding fresh ways to heal, connect, and revitalize eros. Whether you are dealing with sex that has become routine, differences in preferences or desire, aversive reactions to sex, or bodily changes, erotic difficulties can be a portal to creativity, compassion, and unparalleled growth.

***

If you can find a path with no obstacles, it probably doesn’t lead anywhere.

— Frank A. Clark 1

Kyle, an attractive man in his late fifties, has felt sexually insecure for most of his life. Dressed in red high-tops and loose-fitting jeans, he shifts uneasily in the overstuffed chair. Looking downcast, Kyle tells me that he was a “terrible” lover in his twenties and thirties. When performance anxiety surfaced, Kyle “fled the scene” afterward to avoid exposing his feelings of inadequacy.

On his account, it was something of a miracle that Kyle met Sienna when he was thirty-nine. As a teenager, Kyle’s secret fantasy was to be initiated into the mysteries of sex by an experienced older woman. Some twenty years later, Sienna certainly fit the bill. She was a compassionate and assured forty-five-year-old who also loved sex. Moreover, the chemistry between them was so intimate and safe that Kyle’s worries seemed to vanish. For the first time in his life, Kyle felt like a competent lover.

That feeling lasted for the first six years of their marriage. Then, small mishaps before or during sex would rattle Kyle, causing his erection to wane. Consequently, worries about performance are preoccupying him again. In our session, Kyle wonders, “What is the source of my anxiety? Why is it back? Can it change, or am I destined to feel like a sexual failure for the rest of my life?”

Kyle is, understandably, disheartened, but he’s asking the right questions. Why, after so many years of empowering sexual experiences, is Kyle avoiding sex with his wife? What is behind his anxiety, and can he break free of lifelong patterns that leave him feeling sexually inadequate, dissatisfied, and stuck?

The Hidden Factors: Our Eros-Inhibiting Imprints

As a sex therapist, I’ve had many clients who struggle with sexual anxiety. When preoccupations take the joy out of sex, I suspect that imprints are at work. Many of our unpleasant or downright triggering reactions to sex are due to sex-negative messages that imprint unconsciously early in life. For this reason, I call them the “hidden factors.”

So, while billed as a fun, pleasurable, and connecting activity, sex also has a darker side. Even in — and indeed because of — the trust and love in a safe, committed relationship, our lovemaking can stir up unpleasant emotions and body sensations.

In the West, we mostly try to solve problems or avoid them. We may seek “happy endings” while shunning the complicated emotions that arise when we get triggered. While avoiding sex may seem preferable to feeling anxious and ashamed, when we erect barriers between ourselves and our pain, our issues don’t move. For this reason, avoidance can impede our emotional, psychological, sexual, and interpersonal development. However, when we approach our hidden factors mindfully, they become a portal to healing and transformation.

Five Features of the Hidden Factors

To start our healing, we need to recognize the five main features of the hidden factors. It is also crucial to know why “trying to figure it out” only takes us so far:

- We get potent sexual education lessons from our earliest imprints, or memories-as-learning, that are “known but unremembered.”2

- These experiences, along with the family, religious, and cultural messages we encode, become the basis of internal models and beliefs that shape our erotic lives, outside of awareness.3

- We can think of our hidden factors as emotional and bodily tattoos — durable but invisible at first because of the arousal surge that accompanies a new sexual relationship.

- Our hidden factors remain invisible until we bond as a couple. Then they start to generate unpleasant reactions, confusion, and sometimes avoidance of sex.

- They are triggered by — but also illuminated by — the “black light syndrome,” which in scientific circles is called state-dependent memory.4

Let’s expand on these features to understand how the hidden factors cast a pall on our erotic life.

Imprint Portfolios: Our Sex Ed That Is Unremembered But Not Forgotten.

Way before the “birds and the bees” talk (if there ever was one), you were observing how your caregivers wore their sexuality, whether openly in bold, colorful designs or “buttoned up” in muted textures and hues. You were sensing the feeling tone when conversations featured sex, even though you were probably too young to understand them fully.

As with everything we learn, our sexual education is not merely a verbal discourse; it is also an emotional exchange5. We are resonating with the messenger's state as conveyed by their facial expression, posture, and voice tone. These experiences encode in the deeper structures of our brains outside of conscious awareness, which means they are difficult — if not impossible — to recall6. Moreover, the takeaway of this early emotional learning lasts longer than words ever will7.

Without words, by eighteen months of age, we have already established internal models of how others will treat us and how we have to be to survive in the world8.

Our models inform our general beliefs and our attitudes toward sex. Additionally, in whatever way we identify — ethnically, racially, culturally, and sexually — we all imprint our subgroups’ models of healthy, appropriate, and “hot” sex, and perverse and “wrong” sex. Most likely, you have models that prevent you from expressing yourself sexually as fully as you desire.

Some limiting beliefs are specifically about sex. They can show up as, “Sex is dirty or dangerous,” or “I’m bad for enjoying pleasure.” If this is the case, we will hide or exile our desires or feel guilty if we “indulge.” Our implicit models about sex are often knotted with more general models about self and others in eros-inhibiting ways.

For example, if my model is that I’ll be hurt if I open up, I may lose my desire for anyone I love. If I carry a model that “I’m not safe,” I won’t be able to relax into pleasure. If I “know” I can’t shape things to my liking, I will hold back on expressing my preferences. I will wait for my partner to initiate, even though doing so may curb my enthusiasm for sex.

When we identify with beliefs like these, our perceptual filters blind us to experiences to the contrary. We automatically scan for evidence that supports our most ingrained views, and naturally, we find it9. Nonetheless, it’s important to remember that the power behind our hidden factors is that they shape our feelings and behaviors outside of awareness10. For example, we may think oral sex is okay but feel disgusted when we have it.

Emotional and Somatic Tattoos: Invisible but Poisonous “Everything we know and remember — indeed, everything we are, our beliefs and values and personalities and character — is encoded in the connections that neurons make in our brains.” — Sharon Begley11

The extent to which the coupling of our neurons affects us is truly epic. Early sensory and emotional imprints shape our thoughts, psyches, bodies, and sexuality without us knowing when or how they have taken root12. They are like emotional and somatic tattoos, made without our knowledge or consent in poisonous, phosphorescent ink. These tattoos cover our bodies a little or a lot, but we all have them.

Just as implicit rules of grammar shape our speech, our implicit learning determines how we make love, whether or not we issue or accept advances, and what we find aversive and arousing13. Moreover, our initial associations between one thing and another — such as sex and shame — are the most enduring. Once experience goes into long-term storage, it wants to stay there for keeps, even in conditions of dementia14.

Out of Sight: State-Dependent and Automatic

We usually can’t recall the experiences filed in our emotional memory because they encode outside of awareness.15 However, certain sensations, smells, words, and activities during sex act as cues that trigger our hidden factors.16 Then, everything we’ve learned about sex — implicitly — rushes forward, often as a body memory when we are making love. We may not know what’s happening, only that we suddenly feel triggered.17

To understand why this happens, we need to know a bit about how we make and retrieve memories. One explanation is that our brain functions as a camera and makes photographs of our experiences by firing a sequence of neurons.18 When this same sequence fires repeatedly, these neurons wire together, which is how experience moves from its temporary holding facility into long-term storage.

Memories are “retrieved” when the same sequence of neurons fire again, which is most likely to happen when we are in a similar feeling state to when we took the “photograph.”19 Thus, what we have learned about sex is more likely to be retrieved when we are in a sexual state.

The Bad News and Good News: Black Light Syndrome

A strange and often confusing hallmark of the hidden factors is that they emerge well after the first blush of romance settles into a secure attachment. We may wonder why we could enjoy a vibrant and satisfying sex life before, without getting triggered. It is because early in our relationship, our biochemistry changes. Natural opioids and pleasure-enhancing hormones create a temporary arousal spike that overrides our eros-inhibiting imprints. It’s as if our imprint portfolio goes into “cold” storage for a while. In Kyle’s case, “a while” was six years; but it may be merely six months for some people.

Like a black light revealing a previously hidden image, our bodily and emotional tattoos become ever more visible in a committed relationship. Now our imprint portfolio opens during sex, automatically, and eros illuminates the insecurities and wounds hidden in safe storage in our non-sexual states. For this reason, we may find that our body says, “No!” to the suggestion of sex, even though we want to connect to our partner. Or we end up feeling upset, fearful, embarrassed or exposed when we make love.

At first glance, this seems to be only bad news. The black light syndrome can feel raw and revealing, weighing down on the relationship until we explore these newly illuminated scars in mindful awareness. The “good news” about a committed relationship is that we eventually see the well-formed beliefs that are affecting our sexuality. For this reason, committed sex is very naked, and at the same time, full of healing potential.

How Can We Heal and Grow Through Sex?

Couples that practice awakened intimacy wake up by working through erotic issues as a mindful team. They consciously cultivate something called response-agility,20 wherein they fluidly shift back and forth between making love to exploring barriers that emerge to pleasure and expression. Thus, rather than viewing their presence as a disruptor, these couples welcome the hidden factors' appearance as an opportunity to heal old imprints and shame marks.

Somatic Self-Attunement: A Key to Healing and Growth

The body is essential to accessing and transforming the hidden factors. As we encode much of our early learning in the body,21 working with our “felt sense” is how we gain access to our implicit memory system.22 We can mindfully direct our attention to a body reaction, such as tightness in the chest, and let emotions, images, and memories come into awareness. When meaning emerges through the body, we are engaging in what neuroscientists call “bottom-up processing.”23 This approach works better than trying to “figure it out” cognitively.

Let’s see how a bottom-up approach helps Kyle and Sienna work through a painful impasse.

In today’s session, Kyle wants to understand why he reacts so strongly to Sienna's facial expression when she appears to be unhappy with him. Kyle reports that when he sees that look on her face, he immediately gets angry and shuts down sexually. He and Sienna are committed to undertaking this research as a team and agree to explore the trigger using a skill called mindful coinvestigation.

First, Kyle coaches Sienna to pinch her face and furrow her brow in a particular way so he can study his aversive reaction. She tries it, and he does some tweaking until he feels a clench in his stomach, and says, “Yes, exactly!” Next, Kyle closes his eyes and becomes mindful. He is entering an open, receptive state where he can observe subtle changes in his inner world. At his signal, I instruct Sienna to make the expression again, and for Kyle to open his eyes. He looks at Sienna for about three seconds then closes his eyes to study his reaction to the trigger.

Kyle feels the clench in his belly again. I direct him to stay with it in a curious, open way. After a minute or so of opening and closing his eyes, Kyle reports that there’s something familiar in Sienna’s face, something that reminds him of his mother. He feels a tightening across his ribs and a “sucking in” feeling in his lower belly when he says this. I invite Kyle to stay with the sensations and to study them precisely. When we are mindful, our body sensations can link us to other times we have felt like this.

Kyle begins to remember an unpleasant exchange with his mother when he was likely thirteen. I talk to Kyle in the present tense and ask what is happening between them. Kyle says his mother seems to want him to know that his father does “disgusting” things. She doesn’t elaborate, but it’s clear the “disgusting” things are sexual. She is pinching her face and furrowing her brows as she is speaking. Kyle is surprised, and expresses bitter amusement, to make this connection. He can see that Sienna’s face sometimes looks the same way to him.

I ask Kyle to notice what is happening inside of him now. Kyle is wondering if his mother is expressing disapproval of him without saying so. The young Kyle is starting to feel anxious and ashamed. Kyle tells me that he doesn’t want to be anything like his father, but he is also quite fascinated by sex. After acknowledging his feelings, I ask Kyle what his impulse is as he senses into this bind. He considers this for a while and answers, “I am trying to hide my interest in sex, so I don’t repel my mother.”

A look of surprised recognition comes across Kyle’s face like he sees something about himself in a new way. I ask Kyle how he is doing this hiding. Again, Kyle pauses to explore his felt sense. Eventually, he says, “I am sucking in my belly and tightening my ribs.” Kyle immediately sees the link between his feelings of shame and his efforts to disconnect from his sexuality. He now also understands why Sienna’s look of disapproval is so triggering. It evokes strong feelings of guilt, which he pushes away by extinguishing his sexual feelings altogether.

Kyle tells me he wishes he had a different man than his father to model himself after, someone kind and sexually empowered. I ask if he knows anyone like that. His colleague, Jim, comes to mind. Before we close, I encourage Kyle to go back in time and imagine spending time with a man like Jim when Kyle was a boy. Kyle reports that his belly releases, and his spine gets straighter. It feels very different from sucking in his energy. We take time for Kyle to “photograph” this new way of experiencing himself.